Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Metal 3D printer builds low-angle overhangs without supports

Velo3D’s founder discusses the Sapphire metal printer and the state of additive

- By Don Nelson

- September 20, 2019

The career of Velo3D founder and CEO Benny Buller is as interesting as his company’s new 3D printer and his views on additive manufacturing (AM).

He spent the first decade of his career in the technology unit of Israel’s intelligence agency. While there, Buller, who holds advanced degrees in physics and electrical engineering, developed a system used in the country’s surveillance equipment.

“We did the coolest things you can imagine,” he said of his time with Israeli intelligence. “Imagine something between the [National Security Agency] and Q from the James Bond movies.”

Afterwards he worked in the inspection department at Applied Materials, a California-based supplier of equipment, services, and software for the semiconductor industry. That was followed by a stint in the solar industry at First Solar in Ohio.

Buller then returned to California to join the $5 billion venture capital firm Khosla Ventures. When asked during a recent telephone interview what drew him to the VC arena, he replied: “I’m a scientist. A physicist. I worked all my life with technology and product development. I never was on the ‘business side’ of the business. And, basically, the two years that I spent at Khosla was an accelerated business school.”

One of Khosla’s portfolio companies used AM to build rocket engines. A single palm-sized part took from 13 to 20 weeks to produce, Buller said. “That was shocking to me. When I saw that metal printing was so embryonic, I said, ‘This is a great opportunity.’”

He launched Velo3D in 2015 and began asking customers about the potential benefits of an AM machine unconstrained by the limitations of existing printers. “What if we could make a technology that would not need support structures?” Buller asked them. “All of the customers said this would be fantastic, but don’t think about this because it’s completely impossible.”

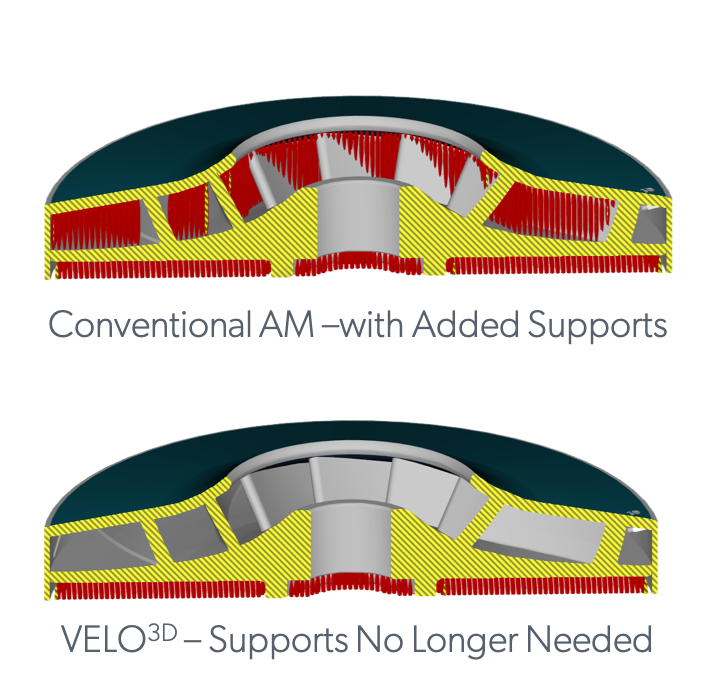

Buller said their attitude challenged him to find a solution, and last year Velo3D introduced Sapphire, a metal laser powder bed fusion system. It’s designed to build unsupported overhangs having angles less than 10 degrees. Generally, 3D-printed overhangs under 45 degrees require supports, which must be removed during postprocessing.

During Sapphire’s development phase, the company identified the failure modes of difficult-to-print geometries, which it calls “primitives,” and devised “recipes”—multilayer process steps—to circumvent these failures. This required the company to design its own laser and scanner controller and a specialized noncontact powder recoater.

Underlying these developments is Velo3D’s print-preparation software, Buller noted. “Our software takes the object, breaks it into primitive geometries, applies a unique recipe for the geometry, and then puts it back together in the printing center.”

Buller maintains that the inability to 3D-print features such as low-angle overhangs hamstrings AM’s acceptance, because it prohibits the building of legacy parts not designed for additive. “No one has the resources to redesign products for AM. That’s not how additive will be absorbed into manufacturing.”

There are many, many legacy parts produced by conventional manufacturing methods that could be 3D-printed if they didn’t need to be redesigned for AM, according to Buller. If additive manufacturers could print exact replicas of some of these parts as is—without being redesigned—that would be a “great breakthrough,” he said. “And this is what Velo3D allows people to do.”

About the Author

Don Nelson

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8248

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI