Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Additive manufacturing’s potential in sheet metal fabrication

The technology is beginning to make its mark

- By Tim Heston

- June 8, 2018

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

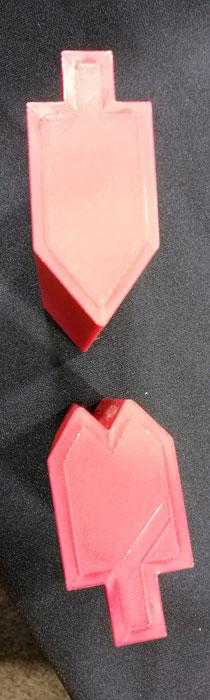

This printed press brake tool set was on display at Cincinnati Incorporated’s RAPID + TCT booth in April. At the time of the show, CI said the concept was still under development, but it also has big potential for certain types of low-tonnage, low-volume work.

Imagine a time when you walk into a car dealership or go online, pick the features you want, and then have the vehicle you just purchased printed up—the engine, the body-in-white, and all.

OK, that probably won’t happen in our lifetimes, but here’s something that probably will. In fact, it’s happening now.

Walk into the front office of a sheet metal fabricator and you see a row of 3-D printers that produce a variety of nonmetallic components, such as polycarbonates and carbon fiber-reinforced nylons. A few even use material jetting to print certain metal alloys, using technology from metal injection molding.

The printers might produce the occasional component needed for a short-run job or prototype, but for the most part they’re not used for production. Instead, they help make production easier.

You walk to the shop floor and immediately understand why. You see bending operators using 3-D printed press brake tools for certain low-volume and one-off jobs. Of course, these tools can take only so many tons of force, but for thin-gauge, low-tensile-strength sheet metal—especially aluminum—the tools work like a charm. No longer must the shop invest in tooling because it doesn’t have the right tool length for a job. The printed dies have shoulders that don’t mar the part’s outside surface, eliminating a polishing operation. And the V die itself can be printed to a perfect width; operators need not resort to choosing the closest available width from the toolroom or catalog. If a design calls for a specific inside bend radius, air bending over that die can form the same floated inside bend radius time after time after time. Sure, the tools may not last forever, but the material that goes into them isn’t expensive, so the shop can always print another one.

You then peer into the work envelope of one press brake and notice something odd: The backgauge fingers have multicolored tips. These custom backstops—again, 3-D printed in the front office—help operators gauge parts with curved edges and other challenging geometries. Moreover, the different colors provide a visual aid for operators, a road map of gauging points for each step in the bend sequence.

You then notice a robotized bending cell and take note of the unusual end effector. It isn’t machined or assembled with off-the-shelf components; it’s printed. It’s oddly shaped and almost looks alive, like the robot grew itself a hand perfectly suited to grasp the part in front of it. 3-D printing has brought biomimicry to the fab shop.

It’s also changed the equation when it comes to automation. Creative robotic end effectors, all designed and simulated in the office, allow the shop to automate more projects than ever. You see other printed end effectors in the joining and assembly department, where a material handling robot grasps a large sheet metal part and inserts it against several pedestal spot welders.

You then step into the quality department and you see a 3-D printed fixture. A laser scans a sheet metal part to compare it with the original specs. Thing is, for the laser to access the points it needs to measure, the small sheet metal part needs to be presented in a certain way, and a 3-D printed workholding device helps do just that.

Next you walk to assembly and shipping. At some assembly stations you see 3-D printed template jigs that help errorproof assemblies, like those involving similar left- and right-hand panels. A jig provides a template that matches every small contour and hole in the sheet metal. If the holes don’t match and the sheet doesn’t fit, the piece is in the wrong orientation.

You then walk back to the office and see an engineer talking with the plant manager in the conference room. On the table you see scale models of large sheet metal assemblies, showing exactly how those assemblies will fit into the customer’s products. And, of course, these scale models were made with a 3-D printer.

Consumers can’t visit a website and print themselves a car, at least not yet. But portions of this hypothetical fab shop story are happening now, and it’s a story I kept hearing at RAPID + TCT, the additive manufacturing event, organized by SME, that occurred in late April in Fort Worth, Texas. So much of the conversation about AM has focused on its potential in high-end machining and fabrication, and the potential is certainly there. High-end fab shops serving the medical, defense, and aerospace industries continue to eye the technology, especially when it comes to the various metal deposition processes that are emerging. In these markets, a fab shop that doesn’t at least consider what AM can offer might be left behind.

Metal fabrication is a unique, broad business, incorporating both high-end shops interested in metal AM—like powder bed fusion and directed energy deposition—and a broad swath of custom fabrication job shops interested in using AM for tooling and fixturing.

“Tooling and fixturing is a great application,” said Rich Baker, chief technology officer for Maple Plain, Minn.-based Proto Labs, which exhibited at the show. The company not only offers 3-D printing, it has extensive machining and plastic injection molding capabilities; and just last year it acquired RAPID Mfg., a custom sheet metal fabricator based in New Hampshire. “At this event, Lockheed showed how it’s extensively using printed fixtures and jigs to simplify assembly. It’s low cost, and you don’t have to undergo the same qualification process [as you do for production parts]. For fabricators, it’s a great application.”

It’s an application that I believe will begin to spread quickly in the coming years, especially considering the low cost of some established 3-D printing technologies. Metal fabricators soon might look at a certain tooling and fixturing requirement, and before anything else, they’ll ask, Can we print that?

In October The FABRICATOR team will launch The Additive Report. For updates, visit www.theadditivereport.com.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI