Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

What Your Weld Color Can Tell You

- By Josh Welton

- Updated May 18, 2023

- September 20, 2018

- Article

- Arc Welding

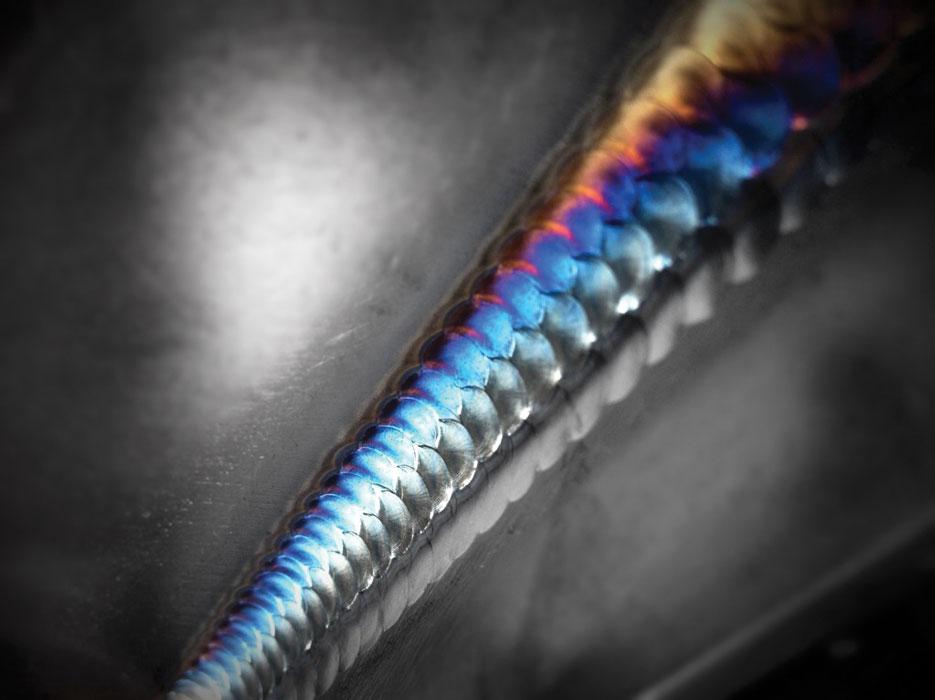

The range of colors that occur in welds can shock the senses and stir your imagination. Sometimes these hues are desirable, and sometimes they are not. How they appear and why it matters both depend on the process, material, the industry, and the application.

To quote Robert Plant:

“A lot of people talk, but few of them know…”

I’m not talking about the creation of the soul of a woman, but rather the genesis of colors in welds. A rainbow of colors in the bead and heat-affected zone (HAZ) doesn’t automatically make it a good weld; it can even indicate a bad weld, but not necessarily. This is where the material and application matter.

The Weld Color of Steel

First things first: Why does steel change color? There is a lot of science involved, and maybe some magic. I’m terrible at explaining science, and chances are you’re not fond of reading science. And if you’re a wizard, you’re probably casting spells instead of welding, or welding with no need for the likes of me. So, I’ll just give the rest of you a quick and dirty version.

When steel heats up, its entire molecular structure changes. And as the surface of the heated steel meets the atmosphere, a chemical reaction takes place. The colors that result depend on the makeup of the metal, the composition of the atmosphere, the temperature at which they meet, and the duration of time the metal is exposed at the elevated temperature. What’s happening is the metal is oxidizing.

Now, surface oxidation is one thing, but deeper oxidation—below the face of the metal—causes porosity. This is where shielding gas or flux comes in, as both are designed to protect the hot welded area from the atmosphere until the bead and HAZ cool below the point at which the steel/atmosphere mash-up won’t hurt the steel’s final properties. When somebody tells you that your weld is colored a certain way because you’re welding at a certain temp, they’re right, but only partially. A lot of factors go into it, and sometimes those colors mean everything, and sometimes they mean nothing.

On stainless steel, for example, any color in the weld or HAZ shows that an oxide layer has formed, which can affect corrosion resistance. The darker the color, the thicker the oxidization. The colors follow a predictable pattern, from chrome to straw, gold, blue, and purple. In some industries, like pharmaceuticals, any color beyond chrome in the weld is unacceptable, but in other sanitary welding situations, such as dairy, shades u-p through light blues are allowed. Those colors can be cleaned off mechanically, chemically, or both, and the corrosion resistance can be restored. And that’s the big deal with using stainless steel, right? Corrosion resistance can be critical.

Of course, if you’re an artist like me, pretty colors are sometimes what you’re looking for. I’ll often sacrifice rustproofing for the sake of looks. Because of the chemical makeup of something like 308 stainless steel, a little heat can result in some very vivid colors. But mild steel also can produce nice colors, albeit a bit softer, and even mixing the two can make for interesting results. I often look for hardened steel pieces, like bearing races or old pieces of armor, as the composition lends itself to cool colors when welded or heated.

The Weld Color of Titanium

The story behind titanium is kind of the same, but with one big difference. Instead of just compromising corrosion resistance, atmospheric contamination can actually affect the integrity of the weld—drastically. Titanium is a strong, ductile material, but at elevated temperatures, it likes to suck in hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. If allowed to do so, it becomes brittle. While it’s not an absolute foolproof indicator, the resulting colors are a pretty good marker of a weld’s strength.

Again, it depends somewhat on the industry and use, but typically you’d like the weld and HAZ to be a bright silver/chrome color, or “colorless.” Often a light gold color is acceptable (and sometimes beyond that, depending on the application or code). The less color in titanium, the less chance that it is contaminated or compromised. The caveat here is also similar to stainless: It looks amazing when allowed to react. A lot of hot rod and motorcycle guys will take their chances with material integrity on exposed piping and exhausts because it looks so dang cool when it turns blue and purple.

Weld Color and Gas Coverage

I’d like to add a bit about gas coverage. Yes, gas coverage can have an effect on a weld’s color. But it’s just one of many factors.

There’s a common misconception among fabricators that more cubic feet per hour (CFH) is always better. More gas means cleaner welds, a better arc, and better puddle control, right? In reality, that’s not the case.

For instance, remember when you were a kid and you wanted to put 110 octane race fuel in your mom’s minivan (at least it smelled amazing)? Or even now, when your neighbor thinks that fueling up with 94 octane somehow makes his stock v6 Chevy Malibu a sneaky world beater? Those motors were built for 87 octane gasoline. Below that, you might get pinging, but using anything rated higher than what the engine was designed and calibrated to run on isn’t going to help; it’s a waste. Heck, it might even hurt the motor.

Same thing with inert gas: You want just enough flow to protect the heated metal from the atmosphere relative to the standards you’re welding to. Anything more and you’re wasting gas and possibly causing turbulence in the puddle. The gas flow needed could be different for every job, but as long as you’re getting just enough to cover the weld and HAZ until it’s below the contamination temp, you’re good to go. More won’t help. In some cases that might mean welding in a chamber, but if a No. 6 cup and 10 CFH will do it, there’s no advantage to using extreme gas flow.

I’ll sometimes run test beads and continue to turn my flowmeter down until it’s not giving me quite enough gas, then turn it back up a couple CFH and run it there.

Colors in welds are pretty, and many elements play into their creation. Sometimes they indicate a bad weld, sometimes they don’t.

About the Author

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

The impact of sine and square waves in aluminum AC welding, Part I

How welders can stay safe during grinding

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI