Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Automation, scheduling software drive metal fabricator’s growth

New organizational structure, scheduling automation help maintain the flow

- By Tim Heston

- June 6, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

About 30 percent of TMCO’s workforce are refugees, many from Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Burma.

In 1974 Ronald Temme launched Total Manufacturing Co., or TMCO Inc., out of an 842-square-foot shack with no indoor plumbing. It ended 2017 with $27 million in sales, 180 employees, and 300,000 sq. ft. of manufacturing space in Lincoln, Neb. No planners or schedulers scurry about, trying to squeeze in a hot job or checking the status of a late order. Scheduling is effectively automated.

The company is now run by, among others, a president who grew up in Iraq and went to law school in Syria and an office manager from Iraq who had planned to become a veterinarian. About 30 percent of the workforce are refugees.

Yet according to sources, miscommunication really isn’t an issue. Jobs flow smoothly. Supervisors and department managers focus not on purchasing, not on this or that customer, but on flow. There’s little drama, just production. The company’s organizational structure, software technology, and shop culture help make it all possible.

From the Law to the Diacro

Rafed Rida grew up in Iraq, then Iran, then Syria. He attended Al-Baath University in Syria for veterinary medicine, then left for the states in 1999 to start a new life. He worked at a manufacturing job assembling antenna parts for Nokia and Motorola. “At the time I was looking for a better opportunity, and I knew the wife [who worked in quality control] of a machinist here at TMCO. She said, ‘[We] work for a really great company. You should apply.’ I went ahead and applied, and right away I got the job.”

Early on he recommended that the company hire his brother Anwar, who like him started his metal manufacturing career in front of a machine, this time an old Diacro press brake.

At first the TMCO job was just something to pay their bills. After all, Rafed was trained to be a vet, Anwar a lawyer; he had studied international diplomatic law at Damascus Law School in Syria. Funny thing is, both never left. As Rafed recalled, “I started as a button pusher, but then I started slowly learning how to set up a part in a machining center and understanding G codes. From there I started programming and eventually managing the machine shop.”

After working as a press brake operator for a year and a half, Anwar ran and programmed CNC punch presses. Then six years later he became manager of the entire fabrication department. By 2012 he was project manager, and in 2016 he was promoted to company president.

Recession and Restructuring

The two rose through the ranks during a time of significant change, spurred in part by the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, an inflection point for many businesses. At TMCO, it led to an entirely new way to run the business.

“You learn a lot from those bad times,” Rafed said, “as you uncover ways to streamline.”

Temme launched TMCO as a one-man machine shop in 1974. He didn’t hire his first full-time employee, Chad Wilson, until 1977. (And Wilson stayed on for the long haul, retiring from TMCO in 2016.) After that the scale-up commenced—quickly. In 1982 sales topped $437,000. By the mid-1980s TMCO purchased National Manufacturing, a small fabricator of laboratory equipment, and by 1985 the company broke $1 million in annual sales. In the late 1980s it purchased new fabrication equipment, then in the 1990s it launched its metal and art division, which focuses on metal art installations. During the 2000s it installed its first tube laser, bender, and roller and upgraded its enterprise resource planning (ERP) software. Today the company uses a package from Global Shop Solutions.

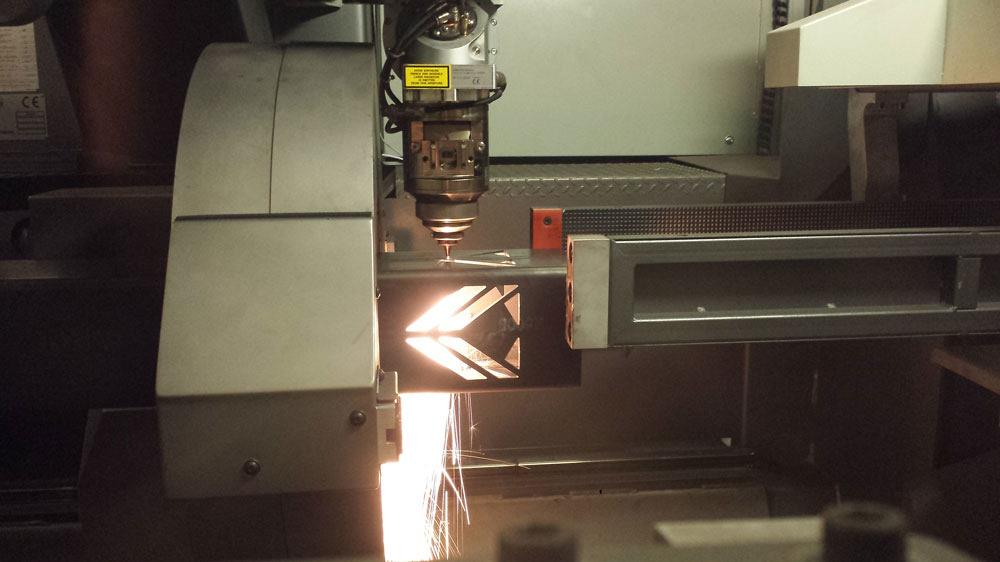

TMCO’s laser cutting department team is a diverse group and includes some from Lincoln’s refugee community.

By 2006 sales had topped $16 million, a medium-sized company in the custom fabrication world. The organization continued to grow until the recession hit. Still, according to Anwar, the company’s bottom line remained healthy even in the face of falling sales and unprecedented challenges in the broader economy. “That’s because we focused on all the waste.”

Up until then the fabricator really ran as a small business—or, more specifically, a collection of small businesses: a machining business, a fabrication business, a tube fabrication business, and so on. Each manager ran his department independently, and each department had its own customer service and purchasing functions.

Growing this way made sense at first. After all, a nimble small shop in the 1970s planted the seeds for TMCO’s robust growth. Even as sales climbed into the millions, scaling up that way helped the shop remain flexible and responsive. For instance, if a manager needed material for a job right away, he had no red tape in his way; he simply made the order and got the material in as fast as possible.

Operating in this fashion did cause inefficiency, though, especially as the fabricator continued to grow. Rafed recalled seeing trucks from TMCO’s material suppliers making multiple trips a day. If people from different departments had talked to one another, TMCO would have ordered a larger quantity and probably gotten a better deal on the material, which is something that was and remains (especially these days) one of the most expensive items on any fabricator’s financial statement.

Routing and scheduling effectiveness suffered, too, as multiple department managers tried to collaborate as best they could. What set TMCO apart was its diverse range of process offerings, from machining to sheet metal and tube fabrication. But scheduling a job that required all those processes, plus outside purchased components? Well, it wasn’t a cakewalk.

In 2008 and 2009 things began to change. “Purchasing became centralized, and centralized customer service came later,” Anwar said. “Basically we told the department managers, ‘We’ll do all the legwork, and everything is going to be ready for you.’ Slowly, we added a team of people who would do all the legwork to run the business.”

From then on department managers wouldn’t have to worry about purchasing or customer service or even scheduling. Instead, their job would focus on productivity, quality, and efficiency—how to get the best work out of their operators in the least amount of time possible.

Scheduling Automation

Having all the legwork done for production sounds great in theory, but how well does it work in practice? Custom fabricators employ dedicated expeditors for a reason. Scheduling a fab shop is an imperfect science with myriad variables. And so shops rely on expeditors who rush to the floor and negotiate for machine time.

Another hurdle seemed to be TMCO’s diverse customer base. Jobs for the art business have vastly different manufacturing timelines than the company’s repeat component business. Could one team really juggle it all?

“Scheduling is a nightmare for every company,” Anwar said. “But we eventually found that, if we really understand the schedule and how it works, and we set it up correctly from the get-go, everything will work. Right now our scheduling happens automatically. There’s no human intervention. Everything runs by itself.”

The company has a range of processes, including machining, flat sheet cutting and bending, and laser tube cutting and forming.

They made it happen by contracting with a software developer to write a program that works with the company’s existing ERP system, and it’s tailored for TMCO’s operation and product mix. Like most custom fabricators, TMCO manages highly complex, multilevel bills of material (BOMs). But behind all that complexity are some patterns. As Rafed explained, “We process many jobs that share common components. Components may be mostly the same, but have different widths, colors, or other variation.”

The scheduling system uses these commonalities to mitigate the swings in capacity demands that anyone in custom fabrication is all too familiar with. The company builds certain components to stock. That inventory is then pulled by various triggers based on customer demand, depending on the nature of the job. At the same time, the company also has orders that use unique components, the manufacturing of which needs to be sequenced so that all reach the shipping department at the right time.

TMCO is like many fabricators in that it runs jobs that fit on a spectrum, with “make to order” on one end and “make to stock” on the other. Some jobs are entirely made to order, with a multilevel BOM consisting of unique components. Most jobs have some components that are made to stock. Some repeat orders require TMCO to manage a finished-goods inventory, while others are shipped as soon as manufacturing is completed.

Having jobs that populate an entire spectrum between make to stock and make to order seems incredibly complex. But as Rafed explained, for the scheduling software’s use, all that complexity can be placed into two categories. “We really just have two types of BOMs, one we call ‘manufactured to job’ and another we call ‘manufactured to stock.’”These two areas make up the basis of what Rafed called a “work order tree.” The make-to-stock BOMs build the branches, while the make-to-jobs pull from those branches to varying extents, depending on the order’s characteristics, including its order frequency, volume, due date, the use of purchased components and outside services, and the specific manufacturing steps involved.

If capacity is available to meet a customer’s delivery request, the software backward-schedules based on the due date. If capacity isn’t available, the system forward-schedules and posts a new, later delivery date. All this happens upfront, before the order reaches the floor, so that managers can take preventive actions.

This could include scheduling overtime or simply rerouting a job on a different machine that has capacity to spare. The key: Delivery problems are tackled and resolved upfront.

All this seems logical enough. A fabrication shop, like many high-product-mix businesses, operates as a system, a series of manufacturing steps that must be synchronized. Software excels at looking at different variables and suggesting an optimal path. Still, one big hurdle remains. As Rafed put it, “Garbage in, garbage out. If you can’t control your processes, you can’t trust the data.”

To that end, the company measures each step and tracks everything. This includes all types of inventory, from raw to work-in-process to finished goods. Every time a job moves, it’s tracked.

In this sense, inventory is counted continuously. Workers clock in and out of jobs and scan bar codes so the system knows that this piece is in that work center or inventory location. Clocking in and out also helps compare estimated and actual processing times.

Like other fabricators, TMCO looks for experienced welders and certain machine operators. But for many positions, including those in the front office, no experience is looked upon as an asset, not a liability.

No Experience? No Problem

Regarding the scheduling system, the devil’s in the details, and mastering them gives TMCO its competitive advantage. And like any fabricator, the company couldn’t do it without the right people. At TMCO, those people don’t necessarily need to come to the job with experience.Anwar and Rafed added that the company does rely on experience when it comes to technical jobs, like certain machine operator and welding positions. But for general laborers on the floor and in the office, having no experience is not a problem. In fact, it’s sometimes preferred, simply because people come to the job with no preconceptions.

“If you hire people with years of experience in certain positions, they might be a roadblock for change,” Rafed said. “They may be used to doing things a certain way. Bringing in new blood is a good way for us to help maintain our culture.”

When the company expanded its customer service department, it hired people with previous business experience, but not necessarily metal fabrication experience. “Even with this business experience,” Anwar said, “we train the person for several months, spending time in every department. It’s very important that when these people visit our customers, they know exactly what our capabilities are. When customers ask a question, they should be able to give an answer immediately, instead of wasting time calling the office to see if we can do a certain job.”

If someone is hired as, say, a general laborer, that person might be offered the opportunity to travel to a machine tool vendor for training. They learn the processes and, essentially, are given the opportunity to climb the ladder, just as the company’s current leaders did.

This has made TMCO popular with Lincoln’s refugee community. “The company owner’s wife is from Japan, and he has an appreciation for people from other countries,” Anwar said. “The first refugee hired on was from Vietnam. He started in the machine shop and just retired last year after 30 years at the company. So that’s how it all started.”

The fabricator does work with Lincoln Lutheran Family Services as well as Catholic Social Services. And it offers English classes to its employees; in fact, it pays them for it.

Having various languages spoken on the shop floor does require good organizational practices. Standard operating procedures are documented clearly using photos and other visual aids, but this happens to be a best practice regardless of how many English speakers work the shop floor.

Anwar emphasized that TMCO doesn’t have a formal policy for hiring refugees. “Your qualifications to do the work are what determines whether we hire you or not,” Anwar said.

But as it happens, many new hires come through word-of-mouth and staff recommendations, a practice common among many fabricators. At

Photos courtesy of TMCO Inc., www.tmcoinc.com.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI