- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

David Madero brings a sense of realism to metal sculptures

David Madero's welding techniques and design skill impart lifelike textures, sense of motion to metal

- By Eric Lundin

- Updated October 25, 2023

- November 14, 2020

- Article

- Arc Welding

Many of artist David Madero’s sculptures are epic in scale. When finished, this sculpture of Christ’s crucifixion stood more than 120 ft. tall. Images provided by David Madero

Around age 5, most of us aren’t too artistic, still taking formative steps with crayons and paper. When a child is rampaging through a coloring book, coloring outside the lines is a given and freeform drawing a bit chaotic. Such drawings usually leave a lot to interpretation, to say the least.

Then again, others among us get a head start in creative pursuits. Metal sculptor David Madero first learned to weld when he was a mere 5 years old. Introduced to welding by his father, an artist who excelled at welding, Madero soon came to realize that red-hot steel was an artistic medium, not unlike the modeling clay that would have been appropriate for his age. And while some parents want their children to be self-sufficient, encouraging them to explore and learn on their own, his father took that idea to an extreme: After showing David some basic welding techniques, he provided no other instruction.

“That ticked me off for decades,” Madero said. Ultimately, he came to understand why his father did so little for him, compelling him to find his own way without instruction from his father or anyone else. Without the benefit of any coursework, he runs entirely on intuition.

“I don’t know how to draw and I don’t know the science behind welding,” he said. “I start with a vision and I use metal to fill space.” Madero doesn’t consider himself a welder. He’s a sculptor who loves metals. As he learned to work with metals, he developed a few signature elements that he uses in many of his works.

David Madero's Visions and Techniques

Traditional sculptures represent people or animals, but many of Madero’s works are a bit abstract. He has the ability to make a sculpture appear to seep out of, or blend in with, its background. In one of his sculptures, a welder doing some overhead welding on a pipe seems to be part of the pipe itself. On a crucifix, the figure of Christ is clearly visible, but the legs and arms disappear into the cross. In yet another, a skull is adorned with a beard that swirls around, forming a sort of base; the base fits neatly over a liquor bottle and the two blend together.

Some of his sculptures have elements that allow the viewer’s focus to wander and then they pull it back. Two oil rig workers use huge wrenches to tighten a coupling on a vertical length of pipe; the implied action orbits the pipe, leading the viewer’s eye from one worker around to the second, then around to the first, then around to the second again. In another, two figures struggle toward each other in an apparent attempt to connect two end links of a vast, looped chain. The viewer’s eye is pulled along the length of the chain and back.

Madero is especially adept at making a static work appear to be dynamic. Many artists rely on years of schooling to impart a sense of flow, but Madero pulls it off extremely well without the benefit of formal instruction. In many of his works, it goes beyond motion; often the exertion is palpable.

Madero doesn’t stop there. He doesn’t put down weld beads just to create weldments; on many projects, he puts down beads to create textures. This is the feature that seems to most clearly define his work. The detail on the pipe welder is so intricate that the welder’s hair, helmet, clothing, and cable each have unique textures that are easy to discern. It almost appears as though the helmet is removable.

A Welder and a Teacher

Initially a sculptor, Madero became a teacher too.

“Social media changed everything,” he said. After many, many inquiries, he realized that social media presented a way to share some of his knowledge, so he uploaded many videos that demonstrate the techniques he uses.

“Every process has its own personality,” he said. He uses many of the most common welding processes—GMAW, GTAW, stick, oxyfuel, and plasma. At the same time, each metal has its own characteristics. His sculptures are mainly steel, but Madero incorporates many other metals, especially alloys of copper, bronze, and brass. Factoring in adjustments at the power supply, or adjusting the mix of oxygen and acetylene, leads to an exponential number of possibilities.

“I’m like a painter who has all of the colors and brushes he’ll ever need,” Madero said.

Of course, most welders don’t see their vocation in that light. People who weld for a living do the opposite, working straight from a strictly defined procedure. They do everything they can to prevent variations and creativity.

“Most welders strive for perfection,” Madero said. A native of Torreón, Mexico, he understands the need for achieving the highest standards possible in welding. Living in an industrial city with a reputation for metals processing, and a big one—the metropolitan area has a population of 1.4 million—means that Madero’s environment is full of people who build bridges, construct piping systems, and weld for all manner of industrial applications.

Madero was surprised and pleased to find that many people who work in the strictly regimented world of industrial welding take an interest in artistic welding. He saw no purpose in keeping his techniques under wraps.

“The mode isn’t precious,” he said. “It shouldn’t be hidden.”

He went further than posting videos when he developed a weeklong welded art workshop, which he conducts about once a year. His courses demonstrate the many things an artist can do with a weld bead—creating textures, running a weld bead over a weld bead, making creative and unusual patterns, and even laying down freeform beads with no clearly discernible patterns. He conducts some of his clinics at welding schools and others are held in manufacturing facilities.

“Companies and welding schools invite me to give these freeform welding courses, and it’s sort of like a week off for their welders,” he said. “In their work, they’re very uniform, but after a few hours of my course, they’re adjusting the welding current, creating swirling patterns, and doing all sorts of crazy and creative techniques. By the end of the week, every student has finished their own work of art, and the level of satisfaction and pride in their eyes always gives me joy. And I’m always keeping my eyes peeled for those who are extremely talented, welders who could easily make a living as metal artists.

No Starving Artist

Madero has been building sculptures for more than 15 years, involved with social media for about 10, and conducting classes for seven. Each complements and reinforces the other, helping expand his reputation in the art world.

Like many top-tier artists, Madero doesn’t sell any of his works in shops and doesn’t even display them in art galleries. The caliber of his work prices him out of the retail environment, and galleries don’t know what to do with welded sculptures.

“They want stuff that they can sell quickly, like bronze statues,” Madero said. “Fabricating is straight-up craftsmanship, and they don’t know how to sell that.”

So he earns a living strictly by making sculptures on commission, and some time ago he was contacted about a project that could be described as the pinnacle of commissions. Representatives of the largest integrated steel producer in Mexico, Altos Hornos de Mexico, asked him to build a large-scale version of the symbol of Mexico, an eagle devouring a serpent. When completed, the sculpture would be placed on permanent display in the Bosque de Chapultepec, a 1,700-acre park in central Mexico City, one of the biggest public parks in the world. Home to several museums, a zoo, and the largest cemetery in Mexico, the park is also the location of Los Pinos, which until 2018 was the presidential residence. The sculpture would be located just a few minutes’ walk from Los Pinos.

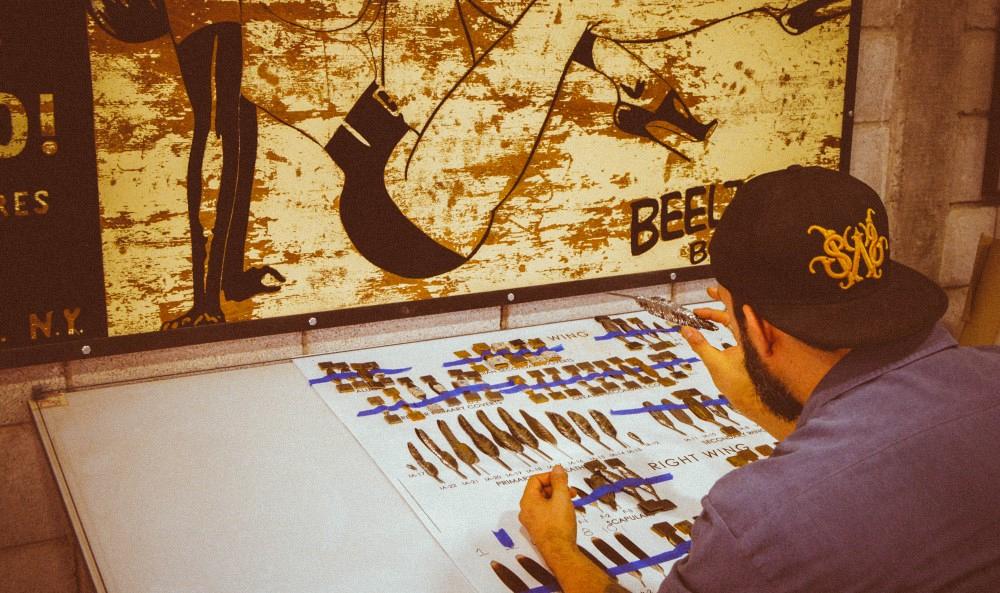

A work in 5 tons of steel and standing 24 ft. high, the sculpture took two shifts working around the clock for five months to complete. Titled “La Fuerza del Espíritu" (“The Force of Spirit”), it has details that are so exquisite that they defy belief. The eagle doesn’t appear to be covered in feathers; Madero made thousands of individual feathers. Likewise, he made thousands of individual scales to cover the snake.

The implied motion of two oil rig workers, which revolves around the pipe, captures and keeps the viewer’s attention.

“I love learning new things,” he said. “I spent weeks studying eagle anatomy—the wings, the beak, the talons, everything.” The wings alone are worth many days of study in that feathers that cover them comprise seven types: primaries and secondaries, coverts (primary, secondary, and marginal), alulas, and scapulars. As on an actual bird of prey, the feathers on the wings and body of the sculpture tend to be uniform in shape and orientation, but the feathers on the legs aren’t as orderly.

On the snake, the scales lie flat where the contours of the snake’s form are gentle and splay where the snake’s body is curved more aggressively. The bird’s talons don’t just grip the snake’s body; one of them is penetrating the scaly exterior.

This isn’t a level of detail he pursued just for this sculpture. Artists don’t turn up the volume when it’s necessary and turn it down when they want to. It might sound like a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder, but this focus on attention to detail, and striving for perfection, is what it takes to establish a reputation as a top-tier artist.

His reputation has grown so much that the work load is beyond that of a single craftsman. To that end, he founded his own company and has a staff of people to handle the don’t-get-your-hands-dirty work, such as running the office and maintaining the company’s social media presence by writing content, taking photographs, shooting video, editing everything, and uploading all of it. He also has a team on the get-your-hands-dirty side of the business, craftsmen who share his vision and work under his leadership to help turn Madero’s concepts into reality.

Building a Reputation in Metal Art

His reputation has grown beyond the art world. A partnership with ESAB and a subsidiary, Victor, introduced Madero to many people in the welding community. As part of an arrangement in which the companies are Madero’s exclusive welding and cutting equipment suppliers, they invited him to Chicago in 2019 to attend the FABTECH expo. In support of ESAB’s We Shape the Future campaign, he created a sculpture in the company’s booth to demonstrate techniques and possibilities.

“I had never visited FABTECH before,” he said. He was aware of the exposition and had thought about attending, but had never followed through. “Now I plan to never miss a show,” he said.

His reputation went so far as to get the attention of clothing manufacturer Dickies, which partners with creative types as varied as a vintner, a luthier, and a chainsaw artist in a program called “United by Inspiration, United by Dickies.” Highlighting the many variations of Dickies products, the campaign stresses the clothing’s durability, favored by manufacturers and craftspeople in many lines of work; warming and cooling fabrics for working in specific environments; stretchy materials for people who do a lot of bending and kneeling in their vocations; and designs in styles and sizes for men, women, and children.

“Dickies has a lot of appeal to anyone who works with their hands, especially grinding and welding, when the sparks are flying,” Madero said. “I’ve been wearing Dickies since I was 5, and I was even wearing Dickies when the company first contacted me about this campaign.”

Although Madero uses quite a bit of intuition in his work, the basis of his success is countless hours of intense study. To prepare for creating the Mexican coat of arms in steel, he spent hours researching the many types and shapes of feathers on a typical bird of prey.

What can come of a reputation that keeps spreading like Madero’s does? Certainly, he’s interested in maintaining sponsorships and a steady stream of commissions, but his social media presence and the seminars he hosts hint at something that runs deeper. Second only to welding, he enjoys teaching welding.

“It’s good for my soul,” he said. “It feeds me.” A great joy comes to him when he sees students in his seminars start to loosen up, experiment a bit, and then make a complete break from the rigid, structured welding they have been taught. “Anything goes!” is one of his pointers, and he doesn’t limit his teaching or advice to experienced welders. Welding demonstrations are all over the internet, as are instructions and lessons for all manner of hobbies and vocations.

“I’d like to see everyone go out and make something new,” he said. “Not just my welding students, but every single person. Not necessarily high art, but just to do something creative.”

Such a notion is especially meaningful these days.

“A lot of people spend too much time on their computers, and many of us are cooped up at home a lot more than ever before—COVID-19 is having a big impact on a lot of people,” he said. “Nobody should go stir-crazy at home. It’s stressful and frustrating. I encourage people to work with their hands and get past all the frustration.”

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI