Co-Founder and CEO

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Digital transformation, Industry 4.0, and IIoT in the fab shop

Practical advice for metal fabricators sifting through digital manufacturing buzzwords

- By Jason Ray

- April 3, 2020

- Article

- Manufacturing Software

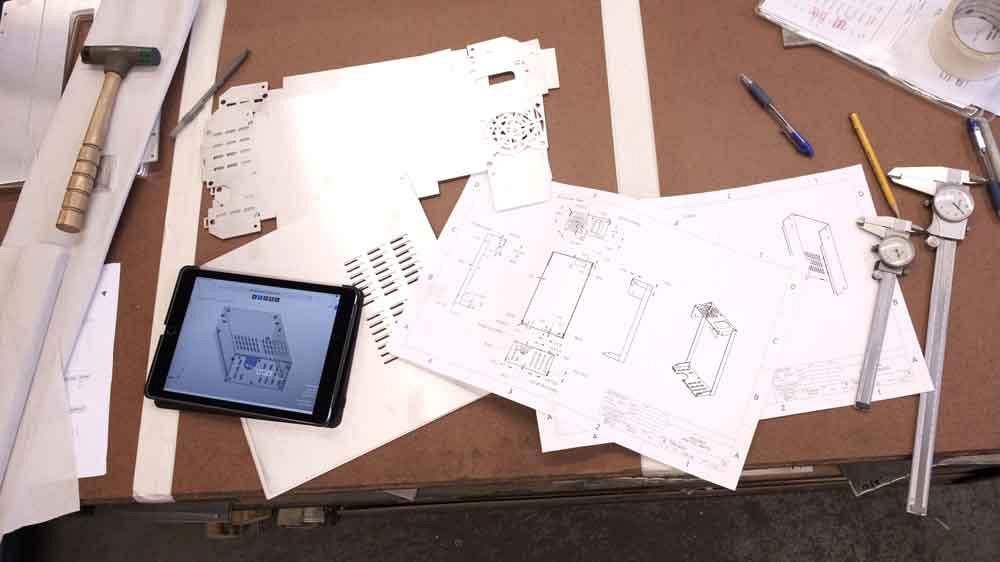

A tablet showing a 3D model complements the paper drawings at a fabricator. Images provided by Paperless Parts

You’ve heard of Industry 4.0, but what does it really mean? More important, what does it mean for small and midmarket job shops? What are the implications for the typical sheet metal fabricator?

For insight, consider the experience of three companies with revenues that range in the millions to tens of millions of dollars. Each provides unique perspectives on what adopting Industry 4.0 technology means to their business. Approved Sheet Metal is a sheet metal fabrication shop in Hudson, N.H.; Sweeney Metal Fabricators, Nashua, N.H., offers both sheet metal fabrication and joined metal components; and Century-Tywood, Holliston, Mass., is a large contract manufacturer for fabricated components, CNC machining, stampings, and electromechanical assemblies.

What Is Industry 4.0—Really?

There is no one definition for Industry 4.0. Of the definitions that do exist, most encompass buzzwords like industrial internet of things, cyberphysical systems, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. Simply put, Industry 4.0 relates to the fourth industrial revolution that foresees a transition from analog and discrete data to digital and connected information. This means that all of the data living in different silos of your business could, and at some point likely will, be gathered through connected systems to form a base of information from which to make better decisions, whether that be by human analysis or, more likely, computer analysis.

This is where machine learning and artificial intelligence come into play. Bottom line, it is all about achieving a higher level of efficiency by using information to implement better practices that reduce bottlenecks, increase production speed, and trim costs.

In speaking with these shops, it is clear that customers are encouraging their suppliers to adopt Industry 4.0 technologies. Peter Marcoux, leading estimator at Century-Tywood, explained that highly technical buyers are mostly between 45 and 65 years old. The new generation of buyers replacing these experienced buyers are much less technical.

“The days of doing business with highly technical buyers who understand exactly what products they are buying are over,” Marcoux said. “New buyers often manage hundreds of items and don’t really understand what each one is. Years ago buyers would almost know how to make the part. Now there is none of that, particularly at the bigger companies.”

The risk in this shift is the change in perception of value. The belief exists that highly skilled manufacturing operations are commodities and that all shops are equally capable of producing any component. This just isn’t true. Harry Ledgard, vice president of sales at Century-Tywood, explained this shift.

“New buyers are report-driven. They have been trained to use PLM [product lifecycle management] systems and grew up with the expectation of instant gratification. So now they expect quick quotes, instant ordering, one-time handling, and no back-and-forth discussions. We have chosen to adopt tools which bring our solutions as close as possible to this expectation to stay competitive, and that is what we have done.”

The big questions he has are: What is going to happen 10 to 15 years from now? Where is that knowledge being cultivated? What can shops do to address this problem?

Ledgard’s advice to a small job shop is twofold. “There is always value in personal interaction—maybe not as much as there once was, which is a product of the electronic era—but in-person, face-to-face interaction is still valuable for building business relationships.

“It all comes down to speed,” he continued. “How fast can you respond to a request? The smaller guys have trouble because they are balancing so many balls, so quoting takes them longer. The key is to find out how they can speed up their response to customers. Most of these guys can’t open models! Finishers typically cannot. They simply have to invest in technology.”

Investing in technology is a great approach to staying competitive. Steve Lynch, former head of R&D at Nashua-based Rapid Manufacturing (now Rapid, a Protolabs Company) and now company leader at Approved Sheet Metal, sees the use of software in small job shops as critical, but cautioned that “Industry 4.0 is not a replacement for skilled jobs in a manufacturing facility. My fear is that shops will create a workforce that is completely dependent on software to do their jobs, and people will become even less skilled because of it.”

This is eerily similar to what is happening with buyers and the use of advanced PLM systems. While this fear exists, Lynch explained that “being a cutting-edge shop makes it easier to hire people. Workers want a high-tech environment and so do customers. The challenge to becoming high-tech is the ability to make quick iterative changes to how things are done to evaluate the result. Standards like AS9100 and ISO are inhibitors to making these quick changes due to the requirement for documentation, which slows progress.”

He acknowledges the importance of these quality systems, though, and Approved Sheet Metal is well on its way to being AS9100-certified. But he’s adamant that “Industry 4.0 is not this massive money-saving endeavor. It helps shops scale efficiently but requires upfront investment for long-term savings.” The question still remains for the average job shop, where cash and time are in short supply, where is the best place to start?

Chris Sweeney, president of Sweeney Metal Fabricators, believes there’s more than just buzz behind Industry 4.0 and sees a lot of potential in the concept of digitization of manufacturing. He said that his company makes it a priority to stay on the cutting edge of technology, even if adopting new tools means upfront investment for long-term gain. As Sweeney explained, “The best place for shops to start is where their need is greatest.”

Chris regularly takes time to step back from day-to-day operations to research new technologies. He then asks the question, “Which of these technologies is best going to help Sweeney Metal achieve our goals today?”

When figuring out where to start, it is important to look at your shop’s value chain and break down the places where discrete data lives. Consider performing value chain mapping exercises. These kaizen-like events help shop owners understand what the real challenges are. Simply drawing the process on a whiteboard uncovers surprising inefficiencies in existing processes and opportunities for process automation.

When looking at the quote-to-cash cycle, shop owners will likely find that their data lives in many different places, and this makes that data hard to use for decision-making. Start at the beginning with the customer request for quote (RFQ). Data is stored either in an estimator’s email inbox or whatever queue system your shop uses to track and prioritize quotes.

More often than not, shops leverage a shared drive to store part files, making future lookup efforts challenging. Up to this point, the data is mostly digital. It is also reality, though, that a majority of the data about each quote and how pricing is calculated resides in the head of your estimator. From clarification phone calls with the customer to unstructured back-and-forth emails with vendors, estimators juggle an immeasurable amount of information. This creates a significant single point of failure for most shops.

When the drawings are finally printed out, as most do to kick off the estimating process, things really start to get analog. The scene is the same across the manufacturing industry: a single estimator walking around the shop with the drawing, asking for feedback from experienced programmers or checking manufacturability with someone on the shop floor, all while making notes on the side of the drawing. At some point this information is assembled to form a final price and is sent back to the customer for review. Often the root source of this information is not documented and resides on the drawing until the quote is sent. These analog drawings are then filed or discarded.

This is the first point in the process where significant data loss can occur. Some questions to ask yourself: Does all of the information your estimator gathers during the quoting process get typed into a system so it can be reviewed when you win the job? Does all of the paperwork go into a physical filing system? Or do you print out those drawings from scratch when the order comes in and start the purchase order (PO) review like you’ve never seen the job before? If we’re being honest, most shops answer yes to the last question, which creates a significant amount of redundant work for your most experienced people.

This is where the concept of Industry 4.0 can be applied to enhance the quoting process and go from analog to digital—a digital transformation. Think about the potential information that could be gathered during quoting to help make your business more efficient and effective.

Based on past quotes, do you know how fast you have to respond to each job to give you the best chance to win it? Do you know if your customers value lead time over price, and for what types of jobs and quantities? How quickly do your customers look at your quotes after you send them? Does that impact how likely they are to place an order? Does the time of day you send the quote matter? Are there specific customers you shouldn’t spend time quoting at all? When should you take the time to really sharpen your proverbial pencil to ensure you are really accurate on your cost/price? All of these are questions that can be answered with data when it is gathered and turned into information. However, this requires that you have the right system in place to do it.

When an order gets placed, materials and hardware are ordered, jobs are programmed, and the manufacturing process is kicked off. In most shops this is a manual process of reviewing the PO, cutting POs to outside vendors, printing routers, and scheduling the work. Each manual step in this process presents new opportunities for automation. Once a job kicks off, there are several places that data can be gathered and turned into useful information.

Also, not all programmers are created equal. How long does it take for a new order to be programmed? How long should it take? Is this driven by quantity or complexity, or the amount of time that was actually quoted? Do your programmers know how much time they have to get a job out on the shop floor to stay under the estimated programming and setup time? Do you know which employees are most efficient with different types of jobs?

A lot of shop owners will answer yes to some of these questions because they have been doing it for decades and are experts when it comes to their business. The challenge is, without a digital system in place that captures this information, how will a new owner know when it’s their turn to run the shop?

The industrial internet of things relates to embedding computing devices in every machine to allow for data to be transferred over a network without human interaction. Throughout the shop floor there are numerous opportunities for this Industry 4.0 technology. Every operation that a part goes through until it leaves the shop presents an opportunity for sensors and data gathering. The use of machine monitoring software has become more common, but often shop owners say that they just don’t know what to do with the information once it is gathered.

Job shops are unique from long-run contract shops in the variety of jobs they are managing at any given time. This makes it harder to look for trends in machine and operator performance. This is not to say that machine monitoring isn’t valuable, just that an investment in this space needs to be thought through and applied with an intentional purpose.

At the end of the day for all of these shops, investing in technology and continuous improvement comes back to taking care of the most important aspect of every job—the customer. In a world where buyers don’t understand manufacturing and are not visiting shops regularly for tours, it’s not enough anymore to just be the shop that delivers quality parts on time. You have to respond to customers quickly, communicate clearly, and manage expectations.

If you can’t handle these initial aspects of a job, how can a buyer trust that you will be able to deliver complex parts on time? Streamlining communication is the best way to give your customers the impression that you are a modern shop that leverages technology to operate efficiently. As Chris Sweeney explained, “Buyers want to work with the shops that are on the cutting edge.”

Jason Ray is co-founder and CEO of Paperless Parts.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI