Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The predictive power of virtual reality in commercial construction

Tech firm tests VR’s potential for structural steel detailing, fabrication, and beyond

- By Tim Heston

- December 15, 2022

- Article

- Manufacturing Software

This simulated rendering incorporates beams, connections, façade elements, stairwells, and even handrails.

Cliff Young remembers sweeping up at his father’s structural fab shop in New Zealand in the early 1980s. He watched as shop workers reviewed engineered structural drawings, then used chalk to draw out details for beam fabrication right on the concrete floor. They were shop floor drawings in the literal sense.

Fast forward a few decades. As CEO of Virtual Image and Animation, Young now helps structural fabricators and other construction stakeholders with virtual reality (VR) simulations. Sometimes they’re used for marketing and sales, such as when a structural fabricator demonstrates to clients exactly how it will produce the steel and work with the erector to make a building a reality. Clients can see animations of the steel being lifted into place right on the screen in front of them. Sometimes, the simulations are used for training, such as when they show detailers exactly how the steel they’re detailing will be fabricated and erected. The simulations show detailers how just one small missing piece of information can snowball into a logistical mess at the job site.

Young and his team might seem as if they’re worlds away from those chalk drawings on the floor. But in one sense, they’re trying to bring the industry closer to those traditional ways, when those who drew also knew (ideally, at least) how buildings were actually made.

From Detailing to Rendering

In 1989, the Young family emigrated to Vancouver, B.C., where Cliff’s father again launched a fab shop of his own. In 2003, Young and his brother launched Anatomic Iron Steel Detailing. “Our dad had a structural fab shop in Vancouver, so right from the get-go, Kerry [Cliff’s brother] and I knew we’d have at least one customer. If you can’t get your dad to hire you, well, you might as well shut the business down from the outset.”

In 2009, Anatomic Iron was working on the Denver International Airport, detailing the hotel as well as the complex diagrid steel canopy that spanned over the airport train station. The structural fabricator, Canam, and the engineer, SA Miro, asked if Anatomic Iron could make a rendering and animation showing how all the steel elements of the canopy would go together in the field.

“We talked with the erectors, planned it all out, and gave it a whirl,” Young recalled. “We took the Tekla model and converted it into 3DS Max. From that we made a 3D animation of how each of the segments would go together. We shared it with the structural fabricator, and they worked with the erection team to plan all the sequencing and crane positions. It was extremely successful, and we soon realized that this kind of simulation presents a lot of value.”

More simulation projects followed, and in 2017, Young spun off the service and formed a separate company, Virtual Image and Animation. Today, the company specializes in simulations and renderings for the construction industry, but it’s also spreading its technology to new markets.

“We’ve done virtual reality games [for construction industry training] and animations for construction projects,” said Kavian Iranzad, who was brought on in 2020 as manager of business development. “But we’re also trying to break into doing animations for other things, such as simulating restaurant operations for different kinds of cooking. We’re a tech company focused on real estate and construction, but we’re not limited to that.”

VR Training

At some point after presenting that initial simulation for the Denver airport, Young recalled speaking with detailers in the industry and discovering just how far removed they had become from the physical act of structural fabrication and erection.

“They’re all at their computers,” he said. “They’re making drawings, but they don’t fully understand who uses them and the day-to-day of how they’re used.”

VR games aid training for fork truck driving (left), welding (center), and even putting together bolted connections (right) on the 80th floor—with a clear view to the pavement far below.

Others felt the same, including those at Industry Lift. Founded in 2018 by Bill Issler—developer of FabSuite (now Tekla PowerFab)—the Williamsburg, Va.-based public benefit corporation is dedicated to developing the skilled trades, and with Virtual Image and Animation’s help, it’s using VR to do it.

As Young explained, “We make the VR software that they can actually use in a VR headset. The most sophisticated developed to date is a steel fabricator simulation. [The VR simulation] shows what it’s like to be a steel fabricator, building a specific piece of steel according to a shop fabrication drawing inside the game. After playing the simulator, [detailers] really understand how their drawing is going to be used by the fabricator.

“The same thing applies on the erection side of things. Our staff can make an erection plan and how to lay out the steel, but they don’t think what it will be like to actually use those erection plans in the field. So again, using VR, we put them in a construction site where they have to take a beam and actually erect it in place. They install the bolts, tighten them with a wrench, all while looking down 80 floors to the pavement below.” He added that the company has modified the simulation to include welded connections as well.

“With this, they understand why it’s so important to have plans that are clear,” Young said. “If the guy up in the steelwork needs clarification, such as what kind of bolt is needed or anything else, he needs to clamber back down to check the drawing again.”

From this, the company has branched into various simulations for training purposes, including forklift driver and crane operator training. In the forklift simulation, students can pick up steel, load it onto a flatbed truck, and learn how to ratchet down the steel and prepare it for transport. In the crane operator simulation, the student operates a tower crane and learns how to maneuver steel beams and place them in the right location.

The company has even developed a weld simulator tailored for the structural fabrication environment. Students learn how to set up a gun, how to don the proper protective equipment (if you strike an arc before lowering your hood, for example, the screen goes white and the game’s over), and how to lay down a quality bead. As Cliff explained, the simulator isn’t as detailed as some of the extensive weld simulators on the market, but it’s not an entry-level simulator either.

“As to where these training simulations could go in the future, the sky’s the limit really,” Young said. “We could have ironworker training, camber machine training, beam line operation, and more.”

Potential for QC

Walk the halls at FABTECH, NASCC: The Steel Conference, or another industry event and you might see someone donning a Microsoft HoloLens. Augmented reality (AR) has reached the construction industry, and for structural fabricators, roll benders, and other related operations in the metals business, the technology has some eye-popping potential.

Young is quick to point out that his company’s current offerings fall into one of two areas: training and marketing. As Young’s team did with the Denver airport project, structural fabricators can use a simulation to sell their services to clients, showing them exactly what to expect and when, and how exactly fabrication and erection will take place on a project.

That said, the next step will be using simulation for quality control, overlaying the 3D Tekla model with the real fabricated assemblies. Young described an example where a fab shop could use AR for the fabrication and assembly of two large, curved steel sections. The design requires that the two sections are rolled and assembled to a specific radius, plus or minus a certain tolerance.

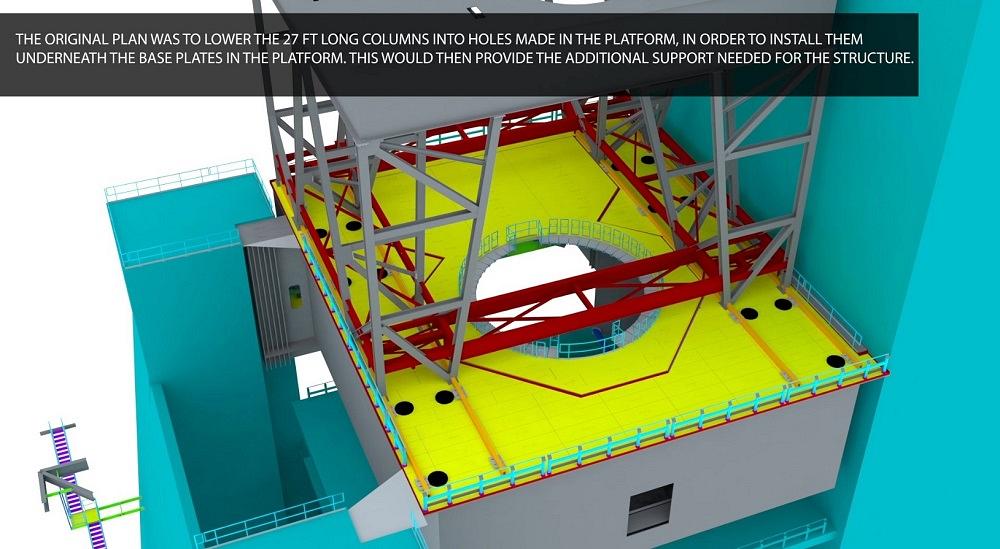

This simulation helps communicate potential problems and offers solutions, all before a single beam is cut.

Here, AR could step into the picture. Imagine a QC technician donning a HoloLens, inspecting those two curved pieces with all related elements tacked together and ready for final welding. The AR would overlay the detailed model so the inspector could compare it with the real assembly. From there, the inspector could verify that, yes, the elements are all tacked together within tolerance and they’re ready for final welding—or he could flag a problem and take corrective action. Taken a step further, the QC tech or operator could don the HoloLens and check the rolled sections after they’re formed, verifying the dimensions and radii are correct. If they’re a little off, they could strategize and plan to accommodate for the variation—all much more efficient than welding the entire assembly up and shipping it out to the field, only then to find the massive structure is out of tolerance.

Such simulations boil down to being able to predict and plan for future complications—a feat Virtual Image and Animation has already accomplished, at least at an upper level, in its work tailored for sales and marketing. Young described a recent animation performed for those constructing the new JPMorgan Chase Building in midtown Manhattan, revealing exactly how the structure’s extremely complex base would be erected, with a series of massive fan-column assemblies supporting the building structure.

“In that case, we did an animation of how the whole building was going to be put up, and especially how the crawler cranes were going to move in erecting the base of the structure,” Young said.

Similarly, the company’s training simulations draw from best practices, allowing the aspiring fabricator to predict what a day in the shop might be like. A detailer learns how his or her drawings will be used. In this way, simulation brings the real world closer to the software world.

Compared to traditional drafting, modern modeling saves countless hours. But at the same time, missing details have wasted countless hours, with requests for information (RFIs) being sent back and forth among project stakeholders. Too often, projects fail to move forward not because fabricators or other parties lack capacity, but because someone hasn’t answered an email. Simulation, VR, and even AR technology could help ensure those details aren’t left out in the first place.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI