Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Lean manufacturing continues to find a better way

Process improvement has become a cornerstone for metal fabricators and other manufacturers

- By Tim Heston

- Updated June 30, 2020

- June 26, 2020

- Article

- Shop Management

The FABRICATOR has devoted a lot of coverage to lean manufacturing and other continuous improvement processes over the years. There’s a good reason for that, writes editor Tim Heston. Getty Images

Custom and contract metal fabricators work to deliver quality fabricated products—all at the right price, quantity, and time—for a multitude of customers. A diverse customer mix helps a fabricator mitigate downturn risks. As of early May, such customer diversification has been a saving grace for some fabricators during the COVID-19 crisis, especially those serving essential supply chains.

Thing is, juggling disparate demands for dozens or even hundreds of different customers isn’t easy. The juggling act isn’t perfect. It’s why a job’s “touch time”—when people or tools actually contact the job or workpiece—can be measured in minutes and hours, though it still takes days or weeks to actually deliver the order. Keeping the flow and minimizing the time jobs sit between manufacturing steps are what continuous improvement is all about.

The FABRICATOR has devoted a lot of real estate to covering improvement strategies over the years, including, not least, a monthly column on the topic by Jeff Sipes, president of Back2Basics LLC. He’s preceded by the late Dick Kallage, who wrote his Improvement Insights column for us for many years. Before that, Shahrukh Irani’s JobShop Lean column detailed how concepts of lean could be adapted for the high-product-mix environment.

Lean manufacturing, quick-response manufacturing (QRM), the theory of constraints, operational excellence, and more all have graced the pages of The FABRICATOR, and for good reason. They all serve a mission of the magazine and its publisher, the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, International: to help metal fabricators succeed.

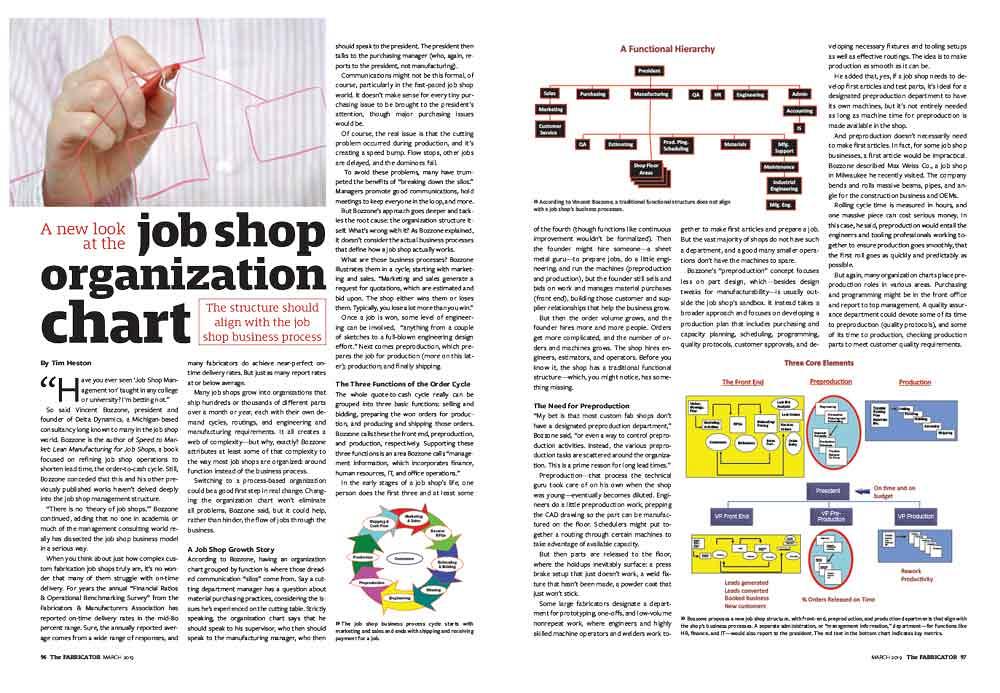

Rethinking the Org Chart

Some strategies require out-of-the-box thinking, and a few strategies from Vince Bozzone of Delta Dynamics certainly fall into this category. Bozzone has studied how custom fabricators and other job shops operate. He’s seen jobs being “thrown over the wall” to estimating, engineering, scheduling, and, finally, the shop floor. Every individual works on his or her piece of the puzzle without ever seeing the whole picture.

They don’t do this out of spite. No one wants to be inefficient. As Bozzone explained, the conventional “functional hierarchy” org chart hinders logical work flow and teamwork as it applies to the job shop business process, from the first quote to the final shipment. Sales, engineering, manufacturing, and purchasing all report to a president or similar top executive.

People “throw jobs over the walls” because, well, the walls exist in the first place, put in place by the functional hierarchy. Why not reorganize to reflect how jobs are truly processed through a shop? Jobs flow through sales, quoting, and order entry (the front end); engineering, planning, and tryouts (preproduction); and, finally, the fab shop floor (production).

The success of each department is measured in part by how smoothly the work flows downstream. All the idiosyncrasies—be it in cutting, forming (tooling, bend sequence feasibility, etc.), welding, grinding, or coating—would be addressed in preproduction. Once the job hits production, everything should be smooth sailing. OK, this is the real world, and shop floor surprises are bound to happen. But as Bozzone explained, the shop’s organizational structure should work toward that smooth-sailing ideal, not against it.

Order Processing

People and equipment can move mountains to deliver an order, but the shop has to win that order first. Moreover, a company can avoid problems with the right preproduction process.

Bill Ritchie of the Tempus Institute, a QRM consulting firm, has advocated the quick-response office cell with a cross-trained team of estimators, engineers, purchasers, and production planners working together to deliver a job downstream. He also has suggested that fabricators scrutinize the quoting process itself. A job might be quoted down to the nickel, but by the time it’s sent to the prospect, someone else has probably already won the work.

Make Flow Predictable

Improvement in the often chaotic world of high-product-mix metal fabrication boils down to making work flow predictable. Kevin Duggan, president of the Institute for Operational Excellence, outlines the process in eight steps: (1) Design lean value streams; (2) make lean value streams visual; (3) make flow visual; (4) create standard work for flow; (5) make abnormal flow visual; (6) create standard work for abnormal work flow; (7) have employees in the flow improve the flow; (8) perform offense activities—that is, grow the business.

With all this, employees know where the work is (No. 1); see how it flows, know what’s coming next, and know how to process it (Nos. 2-4); can identify what’s not flowing as it should (No. 5); and ultimately know how to deal with that abnormal flow and improve existing flow (Nos. 6 and 7). This leaves managers free to grow the enterprise (No. 8)—to work “on” instead of “in” the business.

Once flow is obvious and visual, pull systems can take root as downstream operations “pull” what they need from upstream. Continuing to load the shop to keep machines and people busy doesn’t mean more orders will ship. If jobs are just going to pile up somewhere, then why push them to the shop floor? WIP will increase, take up limited floor space, wreak havoc on workplace organization, and impede flow.

Drew Locher, president of Change Management Associates, described how job shops have successfully implemented pull systems to control flow. Orders are pulled in sequence to meet the demands of production. For instance, the welding department pulling the next order triggers events like order releases, purchase orders, and upstream processes like cutting and bending. The result: All components for a job flow quickly from one workstation to the next and arrive at final assembly at just the right time.

WIP buffers are still there, of course, to account for demand and cycle time variation—but not too much. As Brad Muir of Technical Change Associates and others have described in the pages of this magazine, the more WIP a shop has, the longer it takes for the order to make its way to the shipping dock.

Building Organizational Energy

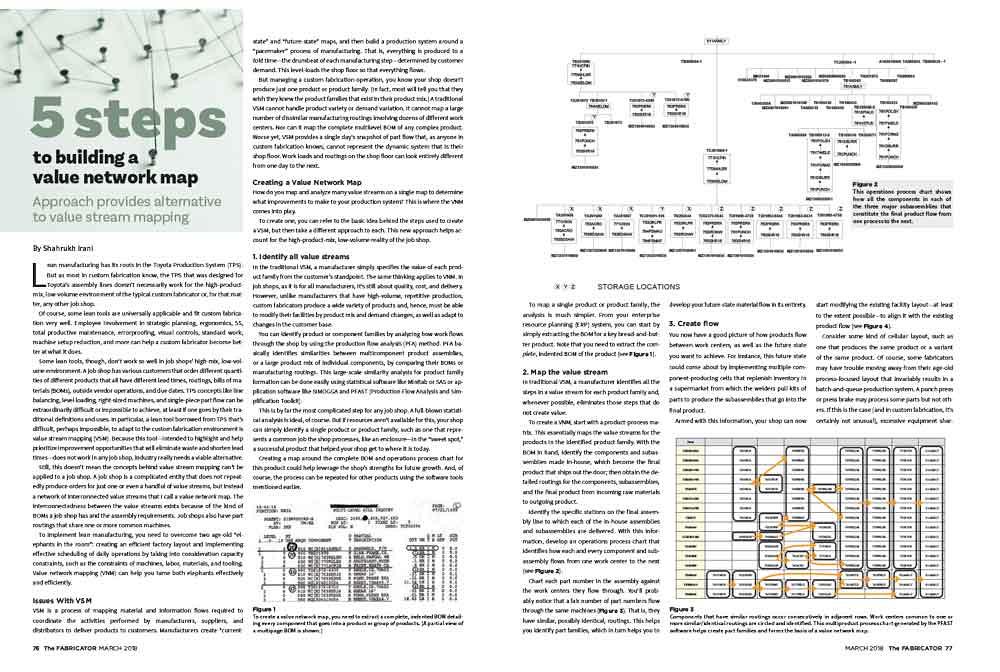

A few years ago Gary Conner, senior consultant for the Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership, described a new value-stream mapping method tailored for job shops. He uses weighted-average cycle times to do it. Shahrukh Irani, president of Lean & Flexible LLC, described how job shops can analyze product mix by not only products and quantity, but also routings, revenue, and demand repeatability. He also proposed value network mapping, a mapping method that’s tailored for the job shop environment.

Fabricators have plenty of improvement options to choose from, and which works best depends on the specific fabricator and its mix of processes and people. The right combination of improvement techniques can make a fabricator successful financially, but it also can create a more enjoyable place to work. That’s not only because everything seems under control and less chaotic, but also because of an underlying energy. People believe in what they’re doing. It’s not just a job. Kallage called this “organizational energy,” which he described in one of his last columns before he died in 2016.

“A low-energy company can transform into a high-energy one simply by dumping the factors that bleed energy and replace them with ones that generate energy. Interestingly, the companies with very high energy often get that way because they were facing failure. They had been low-energy dullards before they got the life-or-death message in very clear terms. This does tend to focus the mind and generate organizational energy. Great companies keep that energy and continually regenerate it. Others lurch right back to their prior state and repeat the process until failure is absolute.”

Great people make great companies, and the right mix of people, with good leadership and the right processes, can overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. The next few months will put this theory to the test as we emerge from the pandemic. But in all likelihood, fabricators with high organizational energy will prevail.

Years of Improvement Strategies

The FABRICATOR has covered many operational improvement strategies, including those from various experts who focus on job shops and other high-product-mix environments. Below is just a partial list of contributors. To find past articles, click on a contributor’s name list below to find their articles on lean manufacturing.

- Vincent Bozzone, Delta Dynamics Inc.

- Gary Conner, Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership

- Kevin Duggan, Institute for Operational Excellence

- Shahrukh Irani, Lean & Flexible LLC

- Drew Locher, Change Management Associates

- Brad Muir, Technical Change Associates

- Bill Ritchie, Tempus Institute

- Jeff Sipes, Back2Basics LLC

- Rajan Suri, Center for Quick Response Manufacturing

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

Young fabricators ready to step forward at family shop

Material handling automation moves forward at MODEX

A deep dive into a bleeding-edge automation strategy in metal fabrication

White House considers China tariff increases on materials

BZI opens Iron Depot store in Utah

- Industry Events

Laser Welding Certificate Course

- May 7 - August 6, 2024

- Farmington Hills, IL

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,