Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Reduce training time through modularization

Metal fabricator makes it easy to create quality parts the first time by 3D-printing fixtures

- By Lincoln Brunner

- Updated March 1, 2024

- February 27, 2024

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

When Chris Harbaugh and the leadership team at Mundo-Tech hire new people, they want to do more than teach them how to do things quickly. Indeed, they want every employee to do the right things quickly so that everyone in the production chain walks away happy.

Bob and the Tribal Knowledge Trap

“Obviously, whether it’s aerospace or if it’s a commercial job or any industry, the customers want one thing—they want their parts correct,” said Harbaugh, Mundo-Tech’s vice president. “So, we first express how important quality is. You can’t inspect quality into work. The part has to be correct.”

Mundo-Tech, a Rogers, Ark.-based fabricator of tubular components for the aerospace, defense, and commercial markets, has made a science, and a business, out of fixtures for welding and inspection. That focus was born of a need to vastly increase the throughput and accuracy of its tubular parts, a huge percentage of which are used in fighter jets for the U.S. military.

The problem for Mundo-Tech (and everyone else in fabrication) is that the old way of bringing people up through the ranks of an organization—a process through which they gained tribal knowledge from experienced veterans—is for all intents and purposes gone. That tribal knowledge created expertise in the processes that a shop used and resulted in quality parts.

Two problems have arisen: One, most of the keepers of that tribal knowledge have retired or soon will. Two, the processes they used do not produce good parts quickly enough for today’s customers.

“The prior generation of fabricators and fit-up people, they really had to do a lot of math … or they were apprenticed for a long time to be able to take parts, fabricate them correctly, or inspect them correctly,“ Harbaugh said. “So, you’re really depending on people who have had a long history of being in the workforce, doing this type of manufacturing.

“The workforce is different than it was 10 years ago, 15 years ago, when everyone depended on ‘Bob’ in the back shop to take care of these difficult things because Bob knew how to do everything. And God forbid Bob dies or leaves or retires.”

Mundo-Tech, a second-generation family-owned company, has been around long enough to have depended on its own Bobs for longer than Harbaugh would like to admit. The company saw the handwriting on the wall, though, and course-corrected so that now, when new people without that tribal knowledge arrive, nobody talks about Bob. What they do talk about is ensuring that the people who are doing setups and fixturing learn how to create quality parts in a fraction of the time it took Bob and the gang back in the day.

The Fix

So, instead of relying on Bob, Mundo-Tech created a system for Joe—that is, any ordinary Joe (or Jo) who walks in the door. Someone with no tribal knowledge, or maybe no manufacturing knowledge at all. The process was created, in part, to make sure that even if people the company worked hard to train do end up leaving after a year, it can find and acclimate the next worker with minimum lag time.

“We needed to make a process [in which] basically anybody can walk in the door with a high school education and be able to start inspecting and fabricating parts,” Harbaugh said.

That strategy really started rolling about two years ago when it found an ideal vehicle: the fixtures on which the company relies heavily to fabricate and quickly inspect its vast array of tubular parts.

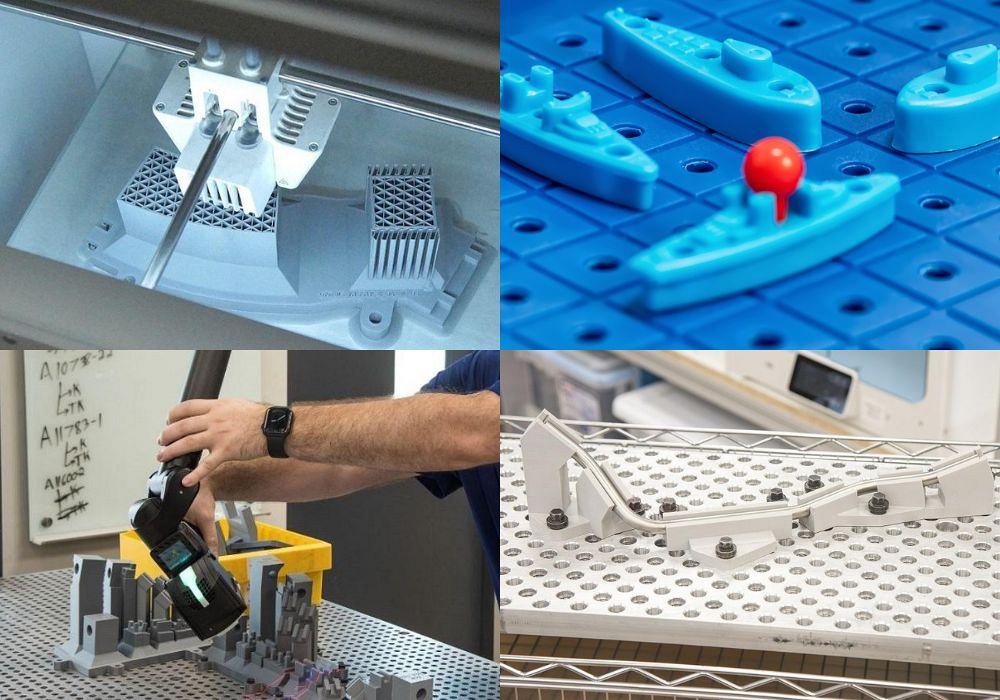

Needing a quick solution to its internal fixture bottleneck, a couple of people on Harbaugh’s team looked around and saw a 3D printer they could use. The fixture they printed could hold a certain part in place accurately while an operator inspects it and marks witness lines for trimming.

So, today, rather than rely on traditional metal or wood fixtures, some of which can take weeks to build, Mundo-Tech prints its fixtures—or more to the point, modular components of fixtures—and mounts them on a custom-made peg board that can accommodate an almost endless variety of components.

Each position on the board has a letter/number designation. Parts, and the fixtures used to create and check them, are listed with the appropriate series of letters and numbers so that anyone can learn quickly how to produce accurate parts on the company’s production line.

That innovation created a way for Mundo-Tech to train people to set up parts quickly and accurately—without Bob helping.

“If you can play Battleship, you can set up fixtures,” Harbaugh said with a laugh.

“Training has been reduced from weeks to hours … for fabrication and inspection.”

Making It Easy Throughout Production

The company uses the fixtures in several of its production processes.

It starts at bending. When operators bend a new part number—say, for an aerospace customer that wants a first article inspection (FAI) report with all the XYZ coordinates included—they typically will bend the part then inspect it with instruments like a TubeInspect machine or a Romer inspection arm. The part normally comes off the bender as a good or nearly good part, but nevertheless, at each bend station, operators have a fixture plate set up. The operator then sets up the fixture (it takes two or three minutes) so they can place that first good part coming off the bender into the fixture to make sure everything matches up. Once that’s done, all they do is drop bent parts into the fixture, mark the necessary witness lines (if any), and it’s on to the next part.

“The nice thing is, it’s point-of-use,” Harbaugh said. “While this tube is bending, you’re dropping the next part in the fixture.

“Also, since you’re bending and checking with the fixture for each part, even if you have one that may be half a degree out—something that’s tweakable—if your first part’s good or close to good, you can see where that place needs to be tweaked because you have a fixture right in front of you.”

Many carbon steel parts don’t present a lot of springback problems. However, with the amount of aluminum and titanium parts the company runs through its bending machines for its defense and aerospace customers, part deformation can become a big problem in a hurry. One recent part served as Exhibit A—a 5-ft.-long aluminum tubular part with nine bends.

One operator fabricating 25 of that part, for example, can use the fixture at the bending machine to place the part and establish where the end of the part is supposed to be. With a tolerance block on the fixture (designated by two lines), the operator knows that if he marks the part between those two lines, the part is good.

The process eliminates use of an inspection arm that records points on the part, reducing measuring time from six minutes to one. With a high-mix, low-volume environment across the company, that time savings per part has been golden. The process has reduced fabrication time across Mundo-Tech’s operation by 25%, simply because the fixturing process has become so uniform throughout.

“We’re not running 1,000 [pieces] of 20 different part numbers—we’re running the reverse of that,” Harbaugh said. “We’re running 1,000 different part numbers with a quantity of 20. You have to have a process that all the parts are able to move through at the same rate and reduce your bottlenecks everywhere.”

About the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI