AWS CWI, CWE, NDE Level III

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

So, you want to become an AWS CWI

The fundamentals—Part I

- By Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

- June 28, 2016

- Article

- Arc Welding

If you have decided to make the big move to becoming an AWS certified welding inspector (CWI) (Figure 1), you will find a somewhat challenging road ahead. Whether you are a welder or an engineer, you will need training that is specific to this task. The passing rate has increased over the years, but only for those who prepare properly. One of the guys in my class was a welding technician for the Newport News shipyards. When he finished the test, he went to his Subaru (the first one I had ever seen), pulled a pint of 151 Bacardi rum out from under the seat, and drank the whole thing! He survived and made it back to the hotel before passing out.

When I took courses to become a CWI, the passing rate was about 15 percent. There were no American Welding Society seminars, and the only game in town was the Hobart Institute of Welding Technology. These guys were (and are) excellent teachers and made the whole thing fun but challenging. (I could name them, but no one would remember them except everyone over 65) There was a review test every morning to awaken us. The homework was well-arranged to take up the evening, so there was no partying or boozing. The instructors were available for advice until 10:00 p.m.

How It Works Now

If you really, really want to become a CWI, it is necessary to take the long road, not a shortcut. Making a quick decision to schedule a time to go to an AWS seminar and then take the exam without what I call pre-prep will make the road much more difficult to maneuver.Several community colleges offer courses for CWI prep. These are not the end of the training, however. In today’s world there is only one way to be sure to get the very best leg up for the test. That is to take the pre-prep and then the AWS, Lincoln, or Hobart seminars. Even if you have been involved in the welding industry for several years, there is much information to digest.

Getting Started. The first thing to consider is whether you have the necessary experience and other qualifications to become a CWI. A potential candidate may go online at aws.org to obtain that information.If you are an educator, you probably will be interested in becoming an AWS certified educator (CWE) at the same time. Take a look at those requirements also. The CWI exam qualifies you for the CWE for an additional fee.

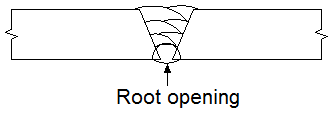

What to Study First. It has been my experience that most candidates need to study the “Terms and Definitions” as contained in the AWS A3 2010. At this time it costs $168 for non-members/$126 for members, but if you really want to get a jump on the “Fundamentals” section of the exam, obtaining this publication will serve you well. Common Misnomers. It is surprising to some with welding experience to learn that a gap between two plates or pipes is actually a root opening as defined by AWS (Figure 2). A stinger is really an electrode holder. An electrode is not a welding rod.The best way to distinguish between a welder as a “person” or a “machine” is to refer to the machine as a power source. One of my pet peeves is the spelling of “welder.” In the old days, a person who welded was a “weldor.” I would like to lead a campaign to cause Mr. Webster to change it. Omar Blodgett of Lincoln Electric says the spelling should remain as weldor.

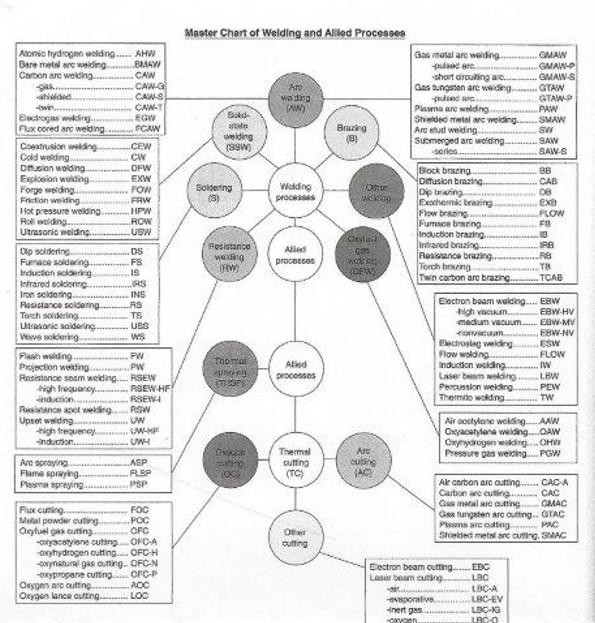

Perhaps the most common of all misnomers deals with the processes.

- Oxyacetylene welding (OAW) is sometimes called gas welding or torch welding.

- Shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) is called stick welding.

- Gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) is called TIG welding or heliarc welding. The heliarc welding term was born from its original use of helium by Union Carbide, Linde Division. When it was discovered that argon could be used as a much less expensive inert gas, TIG was the term used.

- Gas metal arc welding (GMAW) was referred to as MIG welding. This name change came about when it was discovered that CO2 gas worked very well on carbon steel. Since CO2 gas is not an inert gas, the MIG term was no longer correct.

- Flux-cored arc welding (FCAW) was called innershield or outershield. Innershield referred to the Lincoln Electric wire used without a shielding gas. Hobart, Linde, and Alloy Rods, now ESAB, began producing wire that used a shielding gas, usually CO2. Now mixtures of gases can be used in this process. In the beginning, carbon steel was the only wire on the market. Now several alloys, such as stainless and nickel, are available for the FCAW process.

- Submerged arc welding (SAW) has been referred to as flux welding and the original term, union melt. Again, as with GTAW-heliarc, the Linde Division of Union Carbide pioneered this process.

Many new and fairly recently discovered processes are listed in the “Terms and Definitions” publications. The AWS A3.1 publication depicts a Master Chart of welding processes. This is a wall chart that is nice for a classroom in a school or training room in an industrial setting. It also is useful in an engineering department for the nonwelding engineers’ use in preparing specifications. Many textbooks and welding handbooks include the chart (Figure 3).

Specifications and Classifications for Welding Materials

The average welder or even a welding supervisor may not be familiar with the information that is required for a proper welding procedure specification (WPS). The classification are familiar to most personnel in the welding field; however the specifications are usually not commonly used by the shop personnel.F numbers also are required for WPS and welder qualification forms. The welding engineer or technician usually is the person who must be well-informed about this information.

The Importance of Specifications. The specifications for welding materials are found in the AWS A5 publication and in ASME, Section II Part C. The difference (I don’t know why there is a difference, but I suppose it is just to be different) is the numbering. The AWS A5.1 is SFA 5.1 in the ASME publication. These numbers do not have relevance for tensile strength or position like the classification numbers do. Instead, they provide the location of information relating to the product (Figure 4).

An Example of the Content. One very helpful section of the A5 publication is A5.01, “Procurement Guidelines.” This section describes the use of A5. It covers the filler metal classification selected from the pertinent AWS filler metal specification, the lot classification selected from Section 5 of this document, and the level of testing schedule selected from Table 1, Section 6.

As with all AWS publications, experts from the welding industry are involved in developing important documents. Many of the people are well-known to AWS members.

—Jim Hannas has been around in many different areas of the welding field. He has been with the Midwest Testing Laboratory in Piqua, Ohio, and also headed the welding department at the Edison Institute.

—Sam Reynolds was with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Westinghouse.

—Damian Kotecki was with Teledyne McKay and Lincoln Electric.

Committee servants do the work voluntarily, and it takes a long time, sometimes years, to complete the work.

Example of an A5.1 Specification for Covered Carbon Steel Electrodes. The classification for this type of electrode must meet the following criteria:

- Type of current.

- Type of covering.

- Usable positions for the electrode.

- Chemical properties of the weld metal.

- Mechanical properties of the weld metal in the “as welded” condition.

Before the material is accepted by the AWS classification standard, it must meet the criteria as stated in section 5.01, procurement.

To be AWS certified in a certain classification, an electrode must have the marking required by Paragraph 6.0 of Section A5.1. This marking certifies that the electrode has passed all the required testing as set forth in this specification. Some of the required tests are:

- Chemical composition of the core material and of the as-welded condition.

- . Mechanical, usability (position), and soundness (by radiography).

- All weld metal tension test (sometimes called the 505 test), because the diameter of the test coupon is 0.505 inch.

- Charpy impact test (toughness at a given temperature).

The next article in this series will cover details of the classification numbering system.

About the Author

Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

Weld Inspection & Consulting

PO Box 841

St. Albans, WV 25177

304-549-5606

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Welder, formerly known as Practical Welding Today, is a showcase of the real people who make the products we use and work with every day. This magazine has served the welding community in North America well for more than 20 years.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Sheffield Forgemasters makes global leap in welding technology

ESAB unveils Texas facility renovation

Engine-driven welding machines include integrated air compressors

How welders can stay safe during grinding

The impact of sine and square waves in aluminum AC welding, Part I

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI