AWS CWI, CWE, NDE Level III

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Real job shops

Not all fabricating operations are the same

- By Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

- October 22, 2015

- Article

- Shop Management

Kanawha Manufacturing Company in Charleston, W.V., is one of the oldest (maybe the oldest) "job shops" in the Appalachian states. It was formed in 1902 and still is owned by the Davis family. The company originally was launched to build mine cars (Kanawha Mine Cars) for the booming coal industry. Its specialties have varied over the years, but its goal to deliver quality products has not. If you want it, KMC will find a way to build it.

Very few real job shops exist today. Most manufacturers prefer to engage in producing multiples of the same product, which minimizes engineering time and tooling costs. Facilities are organized for an assembly line-type of production, and quality control can be automated. Paperwork becomes so repetitious that the only change may be the date and customer information. Cost studies are simplified and rarely required. Personnel training can be standardized. All this combined allows the mass producer to know the cost of everyday operation.

Every Day Is a New Day for the Job Shop

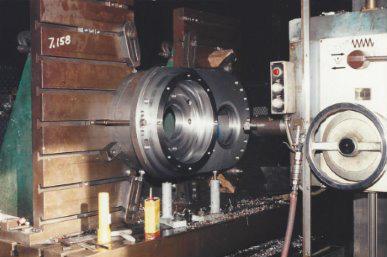

Conversely, job shops must calculate the costs on almost all projects. The shop's machinery can sit idle during some jobs, while other jobs require using every piece of available equipment. This equipment can cost millions of dollars, and only a few shops have equipment large enough for some projects. The machines KMC uses to build the centrifuge parts shown in Figures 1 and 2 cost millions. The completed centrifuge shown with controls and attachments in Figure 3 is massive.

The unit was engineered and built from scratch, its parts completely fabricated by the shop prior to machining. Few engineers in any shop are capable of designing such equipment, especially with varying control systems. Engineering time is a large cost factor when custom units of this type are designed. A job shop rarely encounters duplication in this type of equipment. It is more often than not one of a kind for specific use in one particular industry.

Some centrifuges are used in the chemical industry for producing powdered bleach or barium reduction. Others are used in the wood processing industry to make plywood or pressed wood. The food industry uses the equipment for rendering lard and other animal-based products. Pharmaceutical companies use them to produce powders for medicinal tablets and other products that remain in powdered form. They are used by electric power plants to make coal and wooden particles small enough to be blown into the furnaces with forced air.

Saving the Scrap from Death Row

Jack Reynolds (Figure 4), a sales engineer at KMC, was responsible for serving the "mountaintop removal" industry. He practically lived with the industry for several years. KMC built and rebuilt the huge buckets for the dragline shovels (Figure 5) and used a Boretech welding machine to weld the bores for worn axles and other shafts. The shop also built up the worn cable sheaves.

Reynolds was extremely innovative and able to see needs and provide solutions for the customers. His jobs usually took up a considerable amount of floor space and involved workers from all trades. He could find uses for the old rock trucks with worn-out rock beds and hydraulic systems. Rather than allow them to be transported to the scrapyard, he gave them new life.

One such job was designing and building a utility truck bed to fit one of the old trucks. The configuration was a combination of a fuel and lubricating bed (Figure 6). It probably really didn't need to look good out on a dirty mountaintop, but Reynolds said, "We don't build trash!" You can tell he was serious by the paint job.

The bed was built so that it could be installed on a rock truck or a trailer and tilted so all the fuel could be dispensed. The grease guns were labeled to ensure that the proper type was used for its purpose. Baffles in the fuel tank prevented shifting on uneven terrain.

Reynolds also converted old rock trucks into water trucks, and not just any old water truck, but another jewel (Figure 7). Anyone who has ever flown over a mountaintop removal site likely has witnessed a cloud of dust. EPA regulations prohibit such dust in large amounts. Reynolds and KMC helped enforce these regulations.

The bed accommodated 18,000 gallons of liquid. It could be used for both dust dampening and spreading liquid fertilizer. Again, there were several baffles (Figure 8) to prevent the shifting liquid from shoving the truck over a mountainside.

One of the difficulties associated with this project was how to get it out of town after it was completed. The bed's width was greater than the width of the streets in some cases (Figure 9). Special permits were required, and moving was allowed only on certain days and at specific times. It definitely drew attention!

The Patented Product

Perhaps the most widely known product that KMC produces is its reciprocating coal feeder. The feeder has undergone many revisions over the years but still functions in the same way. A worker at a power plant in Tennessee dubbed it the "shake, bump, and dump machine."

Coal is dumped into the feeder, which deposits it onto a conveyor belt at the desired speed and load size. Smaller units are fairly portable and often are moved about the plant site (Figure 10).

Larger units, sometimes referred to as "multiplex" feeders, are much less likely to be moved frequently. They move more than twice the tonnage of coal in a shift than the smaller feeders.

Former KMC Chief Engineer Bruce Davis, who is now president, designed the belt-driven units. They previously were chain-driven. The belt drive minimizes the noise and is much easier to maintain. If the coal is dropped onto the belt, it rolls off rather than causing the chain to jump off the sprocket (Figure 11).

KMC typifies what a job shop is all about. Nearly no two jobs are alike, and dynamic innovation is what drives the business. The skill level in such a shop must exceed that of an operation that produces the same item every day, a practice that soon becomes automatic and even mundane. In the job shop, the worker must be familiar with multiple fabrication methods and mechanical variations. Every employee requires problem-solving skills, because there is often no precedent for reference.

True job shops are rapidly disappearing, and the older skill sets are going away with the retirees. Technical schools are not able to teach what has been passed down for generations. KMC has employees who are third and fourth generations at the same plant. Hopefully, its retirees will come back and teach the youngsters how to work in a real job shop.

About the Author

Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

Weld Inspection & Consulting

PO Box 841

St. Albans, WV 25177

304-549-5606

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI