AWS CWI, CWE, NDE Level III

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Welding education - the good, bad, and ugly

The evolution of welder training

- By Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

- February 17, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

Welding education has been handled in various ways—some good, some bad, and some just plain ugly. During World War II, several welder-training organizations were established. Some were government owned and operated, and others were independently owned.

When I was in high school in the 1950s, no welder training was available in secondary education in my state, West Virginia, and many others. Most training was provided by shops started by welders who were trained during the war. Veterans’ rehabilitation centers were the only government-supported programs in existence at that time. Welding processes were very limited, partly because the more modern equipment was not readily available in our basically rural economy.

Shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) and oxyfuel welding (OFW) generally were the only two processes taught at that time. The gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) process was taught in only a very few private schools because of equipment costs. High-frequency GTAW machines were as rare in industry as in the schools, which practically eliminated welding aluminum. Some processing of aluminum with SMAW was taught, but it was ugly at best. Using SMAW to weld aluminum required a three-phase DC power source. Few were available except in industrial and defense plants. The engine-driven machines were capable of producing DC, but not many of the small, private schools had such equipment.

The use of the OFW process was far greater than it is today. Many rural areas had no electricity. Farm and mining equipment (mostly cast iron) repair was accomplished with OFW. Cast-iron usage was more prevalent in those days, but was not nearly as reliable as it is now. Water well pumps, automobile parts, and heating and cook stoves were plentiful.

A good brazer usually could be found in a blacksmith shop. Blacksmiths were thought to be fixers of all metals, and rightfully so. They used forge welding, a craft not usually taught in school but handed down from generation to generation. I still have a fireplace shovel that my grandfather forge-welded in about 1910. As a kid, I tried to break it apart but could not. The handle would bend, but would not separate from the shovel.

Shipyards were training in all the available welding processes, and many of our young people went to Virginia, Washington state, and New Orleans for on-the-job training. Some of them returned home and started small, private welding schools. While some of these welders had good skills, they were not necessarily good teachers. A few of these schools produced excellent welders. Some were in it just for the money, and didn’t really care whether a student achieved a good skill level. Some were fly-by-night scammers that took the money and ran; some scammers were caught, and some went back to the shipyards to hide.

Even though the American Welding Society (AWS) and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) provided guidelines, the use of welding procedures was unheard of except in large industrial plants. Small companies did not require welders to be certified. Their hiring test usually consisted of a fillet weld break in any position (most often flat or horizontal) and no paperwork to document skill level.

The really bad and ugly consisted of those who took advantage of the government and the veterans. Every war provides training opportunities for veterans and those who are in the Reserves or National Guard. After Korea, the Berlin Crisis, and especially Vietnam, several organizations popped up to provide training in welding, machining, and HVAC (air conditioning and heating). Many of these organizations were in the game only to take advantage of the government money. At that time oversight was minimal, and the requisite monthly reports could easily be falsified or exaggerated.

Students were paid a token amount while attending the classes and didn’t complain, except for the few dedicated individuals who felt that they were not being properly trained. The equipment was often obsolete and not in good working order. The facilities usually were temporary rental buildings without proper lighting, ventilation, and bathroom amenities. Many were owned by politicians who overcharged for rent and were provided with upgrades to increase the buildings’ value for later profits.

These organizations existed until the 1960s, when grants were provided to the secondary educational systems for properly equipped facilities. The grants also made it possible for adult students to attend. Instructors often were sent to highly recognized schools, such as the Hobart Institute for Welding Technology and Lincoln Electric. The Hobart school was far and away the most diversified institution. The Hobart Brothers taught not only hands-on welding, but also courses in welding theory, procedure writing and usage, nondestructive testing, and instructor training for schools and industrial (on-the-job) training.

I was fortunate enough to be able to attend the Hobart school through Virginia Welding. This company believed in training all its employees, from the mechanics, sales personnel, and delivery truck drivers to even the office workers.

Companies that produced welding equipment and electrodes, wires, and gases began training for using their products. When a new process or product was introduced, the producers provided free training for supply houses and industry. This served as a twofold benefit for the manufacturers of the product and for industry. Those who received the training usually preferred the product that they were trained to use, and the workers performed more efficiently by having confidence in the product and the trainers.

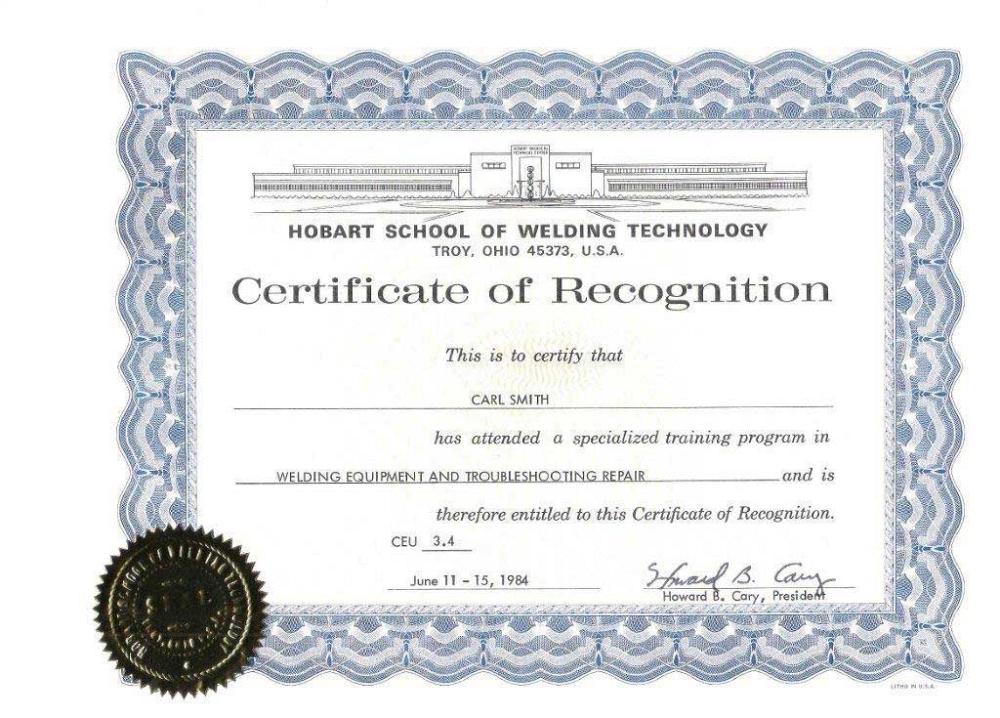

Some companies that provided the training were Linde, Alloy Rods (now ESAB), Arcair and Allstate (also now ESAB). Allstate provided training for maintenance welding, brazing, soldering, and hard surfacing. The Stoody Company was the very best at hard-surfacing training and products. These were weeklong and sometimes two-week sessions. When the training was completed, the participant was given an examination to test for knowledge and proficiency in the use of the products and received a nice certificate (Figure 1).

Unfortunately, this type of training is in short supply these days. Lincoln and Hobart still offer welder training, but not much training exists for welding supply distributors. Therefore, very few supply houses offer demonstrations of their equipment or consumables. But some producers still provide hands-on training and are eager to conduct demonstrations.

Beginning in the 1960s, industry began to realize the value of training personnel. Defense contracts were booming, and there were not enough qualified welders to fill the needs. The FMC Corporation acquired contracts to build the M113 personnel carriers in California and West Virginia. These vehicles were fabricated primarily from 2- to 4-in.-thick 6061-T6 aluminum. This was a whole new ball game for most companies and their welders. Some engineers from California had developed procedures for fabricating this type of aluminum, and they moved all over the country to train engineers, machinists, welders, and other workers to build the carriers.

At that time no welding schools could handle the number of students that needed the training. In West Virginia alone we were asked to train at least 300 welders to weld aluminum.

Linde began producing a power source and wire feeder capable of handling the 1/16-in.-diameter wire with all sorts of adjustment features. Slope, inductance, and voltage adjustments were on the front panel of the power source, and the wire feed speed (amperage) adjustment could be in a remote module fastened to the gun (Figure 2).

The FMC Ordnance plant in South Charleston, W.V., was tapped to be the top producer of the M113. Welds had to be watertight, and the carriers were driven underwater in a pond built specifically for prooftesting.

The state promised to be able to supply the plant with welders. Thus, the large-capacity welding schools were formed. Most of the schools were in rural areas, and the trainees often were required to travel several miles to the schools, which were capable of training 30 to 40 welders on each shift (three shifts a day, seven days a week). Trainees were paid while learning.

None of the local welders had any experience with these welding machines or the amperage required to use the 1/16-in. wire. The heat the larger wire and higher amperage produced required the welders to wear aluminized gloves and bibs. No. 12 lenses had to be used in welding hoods because of the reflection from the bright aluminum. These conditions separated the men from the boys, and some of the trainees lasted only a day or two.

The training created a boom for the welding supply houses, because the trainees were not able to adjust to the spray transfer mode that frequently melted the contact tips and nozzles on the guns. Although the guns were water-cooled, they still burned up quite often because of the training pace necessitated by the rush to put trainees on the job. Linde could not supply the necessary machines and parts to keep up. Hobart began selling motor generators that could produce 600 amps, along with wire feeders and water-cooled guns, to fill the gap. Welding supply sales technicians worked all three shifts, replacing and repairing the equipment and even hauling welding wire in their cars. It was the best of times ever for welding supply houses, and many expanded into new areas then.

When the defense contracts dried up, and the plants began laying off welders, machinists, and other fabricators, new industries moved into the facilities. Luckily, the interstate systems were beginning to flourish, and bridge builders were popping up in many areas. One such company moved into the FMC Ordnance facility. Soon after a railcar company moved in, as did a company that built huge condensers for the power plant industry. So, all the welding training was not wasted, and the retraining for welding the large carbon steel bridge parts and condensers came relatively easily.

Results of Lessons Learned From Organized Training

West Virginia and the other states involved in building the military vehicles learned that it is better to be ready before the work becomes a rush job. Had the officials known how much labor and overtime wages would be involved, they could have had a ready workforce in place much more quickly and economically. This was a wakeup call for the government and industry, and it was taken seriously by all entities.

New federal grants became available for hands-on training and facilities for the training. The Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act was and is the greatest single event for advancement in funding for students. Funding also was available for training the trainers. Many of the trainers who were involved in the Department of Defense projects became trainers in public schools. This was the case in nearly all the new vocational schools, now referred to as “technical centers.”

For the most part, secondary students attended day classes, and adult students preferred the evening classes. Most of the equipment in these programs was brand-new (Figure 3), and some local industries donated nearly new machines.

In the beginning, Hobart was the leader, in part because it offered specialized training to instructors. AWS produced a welding and fabrication training laboratory blueprint, and most vocational schools were built around this recommendation.

Instructors were required to be certified in both SMAW and GMAW for plate and pipe and have five years’ experience in metal fabricating. Fortunately, there was no shortage of applicants. Once they were hired, they were required to take formal training for class curriculum and course topics at a local college. Eventually they were able to acquire a “Master’s Equivalent” certificate (Figure 4). It is remarkable that these teachers did so well in a classroom setting with paperwork. They usually were strictly hands-on craftsmen.

Student enrollment today is not a problem. Most technical centers stay at full capacity, and some have a waiting list (Figure 5). Programs are geared toward qualification and certification to AWS, ASME, or API standards. Sometimes a representative from a fabrication business provides the procedure from his shop, witnesses the certification test, and hires the student on the spot. This is especially true for adult education programs and community and technical colleges.

The certificates furnished by the schools usually allow students to get in the door to take the welding tests for a prospective employer. (The codes require the prospective hires to complete a test for the company or contractor.)

Management Technician Training

Community and technical colleges typically offer a two-year associate’s degree. The curriculum is more comprehensive than those of secondary institutions. The program of study for a welding degree consists of the following (plus the hands-on portion):

- Introduction to Welding Theory

- Basic Blueprint Reading

- Technical Composition

- Welding and Industrial Safety

- Shop Math 1 (fraction-decimal conversions)

- Shop Math 2 (trigonometry, etc.)

- Supervision-Personnel Administration

- Interpersonal Communication

- Industrial Drafting (complements printreading)

- Marketing

- Metal Fabrication (in shop)

- Manufacturing Processes

- Metallurgy

- Business and Professional Speech

- Advanced Welding Theory (procedure development, etc.)

- Commercial and Industrial Practices (how to start a welding business.)

- Weld Inspection (CWI training)

- Inspection Practices (NDE and destructive testing for procedure and welder qualification)

This program has been labeled as a “Welding Management Technician Program.” The prototype was designed by Louis DeFrietis, an instructor at a California community/technical college. He defined the “technician” as a “go-between” to connect the welding shop to the engineering department. The technician assists the engineering department in preparing welding procedures that are workable in the shop. An engineer sees the project on paper, and the technician sees it on paper and in the shop. It is a viable position in all mid-size to large fabrication shops. Instructors for these courses are past or current technicians themselves, because they have real-life experience, and they are better able to convey the needed information.

These technicians are not necessarily AWS-certified welding inspectors (AWS CWIs) or American Society for Nondestructive Testing- (ASNT-) certified NDT technicians, but they must know enough to guide and assist the students toward becoming competent inspectors. Many female students are interested in this type of training rather than the conventional hands-on program (Figure 6), because the technician career does not require excessive heavy physical tasks.

Welder training has really progressed and expanded since the ʼ60s and continues to go further and more in-depth all the time. Secondary programs and the community and technical colleges are now working to form a seamless curriculum, so that the transition from secondary welder education to college is much smoother and avoids course duplication. Credits transfer for all hands-on courses.

Secondary and community colleges, along with Hobart and Lincoln, have expanded their programs and are working to direct the training to specific-need areas, such as the recent boom in the natural gas industry. Most schools now are teaching downhill pipe welding for cross-country pipeline work. This sector experienced a lull for many years, and training slowed, even for the Pipeliners Local 798 in Tulsa, Okla., but it’s bounced back.

Welding education finally has gotten its act together, and it is working (Figure 7)!

About the Author

Professor R. Carlisle "Carl" Smith

Weld Inspection & Consulting

PO Box 841

St. Albans, WV 25177

304-549-5606

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI