- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Small components, big plans

Fabricator uses brains, not brawn, to survive in competitive environment

- By Eric Lundin

- June 4, 2010

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

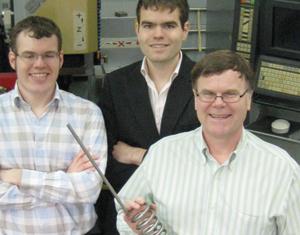

Figure 1: The third and fourth generations of ZMC—owner Bob Zeman and sons, General Manager Dan Zeman and Sales Manager Dave Zeman, show a typical part, a spiral-bent tube used for steam generation. In the background is a key piece of equipment, a Sodick EDM unit. ZMC uses it to make and maintain its own custom tooling quickly and cost-effectively.

Most homes are so completely outfitted with modern appliances—automatic dishwashers, clothes washers, dryers, microwave ovens, electric can openers, and so on—that it is difficult to imagine life without them. Today’s conveniences have removed a substantial amount of work from running a household.

If you dig a little deeper, you realize that even these conveniences have built-in conveniences. For instance, not long ago many appliances had bearings that required lubrication. In the early days, the access point for the bearing was in some hard-to-reach location at the back of the machine. The appliance manufacturers realized that they could make this an easy task by adding a length of bent tubing from the back of the motor to the front of the unit. Routine lubrication was a simple matter of removing an access panel, flipping open a spring-loaded dust cover, and applying a shot of oil.

It might sound quaint now, but in the 1930s this was one of many nagging little tasks that homeowners had to do. And, incredibly, the small peripheral items—the tubing, the fitting, the spring, and the dust cover—sprouted a small industry. In fact, in 1936 entrepreneur Frank Zeman Sr. founded Zeman Manufacturing Co., Lisle, Ill., to serve this tiny manufacturing niche.

When he started the company, he focused mainly on the dust cover, said Bob Zeman, current company owner and Frank’s grandson. It wasn’t long before he was providing the entire oil tube assembly, complete with the spring and fitting, in addition to the dust cover. The company’s work in providing oil tube assemblies led to providing lengths of bent tubing for other applications. The company’s business grew, mainly by word-of-mouth advertising, enabling the company to purchase more equipment to expand the array of fabrication services that it offered, with capabilities in bending, end forming, cutting, brazing, and welding.

Although the company has drastically expanded what it does, Zeman hasn’t drifted far from its roots in small-diameter tubing. The company fabricates tubing from hypodermic size up to 3 in. in diameter, with the bulk of its experience up to 1½ in. A closer look reveals that it also has acquired substantial experience in bending, end forming, and cutting (see Figure 1). This expertise, combined with the efficiency of lean manufacturing and the flexibility of a nearly paperless system, helps the company thrive in today’s cutthroat manufacturing environment.

Leaning Toward Lean Manufacturing

Current trends in manufacturing such as lean and ISO certification are good for high-volume manufacturers. They can help squeeze out needless costs and provide a method for establishing process consistency. Small companies, those that work in low volumes and don’t use many dedicated assembly lines, tend to be skeptical of the benefits of such concepts.

At the same time, many fabricators such as Zeman have seen a rise in competition from foreign suppliers in low-cost-of-manufacturing countries. In response to the threat of eroding margins and the possibility of customers defecting to other suppliers in pursuit of the lowest-priced components, Zeman’s management team looked for ways to strengthen its competitive position. Zeman and the other key managers, his sons General Manager Dan Zeman and Sales Manager Dave Zeman, evaluated the company’s strengths and weaknesses and looked long and hard at all the threats and opportunities. Industry literature indicated that many principles of lean manufacturing would help the company survive, and possibly thrive, despite the many competitive threats.

Before embarking on the lean journey, the company lived by the old rules—keep quite a bit of extra raw material in stock; when an order comes in, set up a machine and run out a huge quantity of parts, much more than the customer needs; store the excess and fill subsequent orders from inventory. This may have been OK decades ago—land was abundant and cheap so storage space wasn’t a problem; machine setup was time-consuming; and recordkeeping was a tedious, manual process. Rather than keep strict control over quantities, it was just a lot easier to produce plenty of extra parts or assemblies and put them into inventory.

All of that has changed.

First, the company no longer stores finished goods. Zeman explained that it stores a little bit of raw material, when the metal has no value added to it, but not semifinished or finished items, which have maximum value.

Figure 2: Sales Manager Dave Zeman, great-grandson of company founder Frank Zeman Sr., monitors the throughput in an automated manufacturing cell. Changing to a cellular approach was a critical step in modernizing and simplifying part flow on the shop floor.

Second, what happens if the customer makes an engineering change, switches to a different supplier, or discontinues the product? Reworking parts, if it’s possible, reduces their value; scrapping them eliminates it. Zeman found this out the hard way when it had to throw out quite a few boxes of finished goods that were sitting on shelves and waiting for orders that never came.

Third, what happens if another order suddenly takes priority? Planning big-batch runs doesn’t provide the flexibility needed to handle order changes. As manufacturers have shifted to smaller, more frequent orders than in the past, Zeman has shifted to this strategy too, allowing the company to react to unexpected orders.

A big motivator for many companies to adopt lean practices is the threat of low-cost products from low-labor-cost countries, notably China.

But much of Zeman’s work is sheltered from the Chinese threat because of its custom nature. Close cooperation with customers is critical. The company plays up its advantages—short lead-times, responsiveness, customer service, proximity—but even so it realizes that price can be a big advantage for an overseas competitor.

“Lean practices have allowed us to keep a lot of business that could have been outsourced had we not had the foresight to eliminate waste and lower our prices without killing our margins,” Dave said.

“The two main problems with parts made in China is that an order takes 14 weeks to arrive, and half the time the quality is so poor that the parts are unusable,” said Bob’s other son, Dan. “We knew we would get a fair share of the business if we could hit three-week delivery targets and provide the quality our customers expect, so we made on-time delivery and minimizing customer rejects the cornerstones of our business,” Dan continued. “We track late orders and rejects, and make this information available so everyone has access to it. However, it does us no good to deliver 100 percent of our orders on time if we are promising six to eight weeks. Many of our customers need orders filled in one or two weeks. Tight inventory control, careful vendor selection, and good vendor relations all come into play,” he said.

“Vendor selection is more than dollars and cents,” he continued. “We make a conscious effort to find vendors who are local and who share our philosophy. We try to cultivate a relationship. To be successful, we feel that forming strong vendor partnerships is a critical component of our strategy. It has to be much more than exchanging e-mails.”

As part of its lean initiative, the company adopted a cellular approach to manufacturing (see Figure 2). Before the manufacturing cells were implemented, a change in a quantity or shipping deadline for an order would trigger changes that would affect nearly every other activity in the entire shop, causing an unending number of headaches. With the cellular approach, many of the processes are separated from each other. Making a change to one customer’s order doesn’t have as much effect, if any at all, on other customers’ orders.

One of the company’s most complicated parts is a bent cupronickel tube used for cooling a motor. The motor is (see Figure 3) for a submerged application, so it is covered with an epoxy to keep it dry. This also keeps the heat in. The OEM added this bent tube, which surrounds the motor and cools it by using the liquid it pumps as the coolant. So far, so good. However, fabricating it was not so good. In fact, the process used at Zeman was far from efficient. In addition to several bends made on several benders, it used several sets of tooling.

“One bender did three or four of the steps, but they weren’t in order,” Dan explained. “It was a flow nightmare. I made a map of that part’s journey through the shop.” The part used to travel across the shop and back and forth throughout the workcell in a complicated, zigzag path.

Figure 3: A cupronickel tube is fitted to the motor it cools. The motor pumps a fluid; the fluid acts as a coolant, circulating through the tube and around the motor to draw away heat. It’s a simple concept that requires a complex part.

They implemented a few lean techniques, such as dedicating specific benders and tooling to this part to make the flow more linear. The company also realized that it would have to bump up the staffing of the workcell from three people to five to optimize throughput. Efficiency shot up 70 to 80 percent, according to Dan, as the time to fill an order dropped from 21/2 weeks to 21/2 days.

It was possible, in part, because the company has a computer system that allows its staff to track everything. It stores both static analysis and dynamic actions, according to Dan.

“Our computer system gives us two broad capabilities: a real-time snapshot of shop activity and the ability to reshuffle jobs to accommodate changing job priorities,” he explained.

“The computer eliminates tons of double entry,” said Dave. “Everything is linked and integrated. As employees enter their day’s work into the computer system, inventory is updated and operational efficiencies are calculated automatically.”

Dedicating machines and tooling to specific jobs, using quick-change tooling where possible, and tracking all the shop’s activities via computer have allowed the company to become much more nimble than ever before.

“Now we treat blanket orders as a series of small orders,” said Dave. “We don’t mind if an order’s priority changes. Our goal is to get customers to place orders as soon as possible—once we have the order in place, we can shuffle it around in the queue as necessary,” Dan said.

Changes aren’t necessarily an inconvenience or a problem. The company has created a structure that adapts to shifting priorities.

“These days we expect changes,” added Dave.

How the company uses its machines, computers, and software isn’t the whole story, of course. The company also streamlined its bureaucracy.

“We used to meet formally once a week,” Dan explained. “Now we have several smaller, shorter meetings instead of one massive meeting,” he said. “We used to have a weekly 12-person meeting that could last up to four hours. This schedule wasn’t flexible because we had to try to cover every issue at once—we didn’t have a way to adapt to changes that cropped up throughout the week. It also gobbled up quite a bit of time because it required everyone’s attendance for the entire meeting, even if just one or two issues were relevant to them.

“Now we have a short strategic meeting involving just three people early in the week,” Dan added. “This is followed by a midweek meeting, usually lasting 30 minutes, involving me, the production manager, and the two division managers. Later in the week I meet with everyone for a brief recap and an opportunity to ask questions and offer suggestions. We also set up quick meetings to go over new jobs or problems as they arise. This meeting schedule takes up a fraction of the time that the old system used and everyone is much better informed.”

Along the way, the company also realized that working with its customers and vendors was too much for a single person. “We have empowered more people, such as shipping and receiving personnel, QC, the production manager, and the division manager, to interact with vendors and customers,” Dan said. “Along the way, we have found that these interactions disseminate critical information more efficiently than going through a point man. They also encourage teamwork, which in turn strengthens communication. It’s a compounding cycle.”

Decades of Change

Many things have changed since Zeman Manufacturing Co. was founded in 1936. Appliances, motors, and bearings all have changed. Sealed, maintenance-free bearings have nearly finished off the market for oil tubes with dust covers. But not completely; a viable oil tube application still exists. You can find it in neighborhoods built when homes were heated with radiators. Many of these homes haven’t been updated to forced-air systems, and the pumps that push the hot water through the radiators still need to be replaced on occasion. Many of these pumps use the original-style bearings, which require a shot of oil from time to time.

Incredibly, Zeman is still a part of this supply chain.

“We still sell oil tubes to one of our first customers, a company that makes the pumps for such homes,” Bob said. Its lean practices and short lead-times should keep this product in Zeman’s portfolio, and out of its competitors’ hands, for many years to come.

Cutting Out the Fat

As part of the company’s attempts to cut the fat, it purchased a saw that uses electrochemical machining (ECM) principles. The company also purchased new lathes. These machines illustrate the company’s lean initiatives (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

An ECM saw creates a simple DC circuit; the current flows between the circuit’s positive electrode, or anode (in this case, the workpiece) and the negative electrode, or cathode (the cutting wheel). A continuous stream of electrolyte flows at the interface between the grinding wheel and workpiece, which facilitates current flow and removes heat. At the workpiece, oxidation of the metal’s surface forms a metal oxide film; abrasives in the rotating wheel continually remove this film and expose a fresh surface for oxidation. Proper electrolyte choice prevents metal deposition on the grinding wheel. The workpiece isn’t exposed to much heat or stress.

“The ECM machine allows us to cut at a much faster pace than before,” said Dan. “Setups take just a few minutes, and the saw eliminated a secondary deburring operation.”

The saw enables efficient cutting on short runs—as few as 10 pieces—and handles runs that number 100,000 pieces.

“Because of the short setup times, we do not have to add expedite charges to fit in small jobs for our local customers,” Dan added. “The machine’s consistency also permits the operator to work on other simple jobs while running the machine, which increases our labor capacity at no cost to Zeman.”

The company also modernized its lathe cutoff machines. They now cut 50 percent faster and setups take half as long as before. The machines’ reliability means that downtime is almost nonexistent, enabling the company to promise quick turnarounds with confidence that it will be able to deliver.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI