- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Tube producer eliminates weld problems one flaw at a time

Weld seam analyzer provides dimensional inspection, unforeseen troubleshooting capabilities

- By Eric Lundin

- October 24, 2016

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Production

Ask 1,000 fabrication shop owners how their shops got started, and you’ll probably hear 1,000 variations of the same story: “My grandfather started a machine shop in his garage ….” Ask how they have survived all the ups and downs that come from running a business for a few decades, and again you’ll hear a couple of common themes: Don’t borrow too much and don’t assume too much. Too much debt and too much reliance on a single market, or a single customer, can wipe out a business in the blink of an eye.

Survival hinges on preparing for setbacks, both temporary and permanent. Business cycles come and go and markets change; keeping debt to a minimum and keeping an eye on market conditions are necessary to keep a business running. The story of Middletown Tube Works and the other companies in The Phillips Group has the same theme.

Although the company is a tube producer, its history mirrors that of many fabricators.

Ralph Phillips opened a small machine shop in 1967 and did a lot of automotive tool and die work. In 1968, as an Army Reservist, he spent a year in active duty, which forced him to close down the business. After five months in Vietnam, he returned and reopened the business, picking up where he left off when his hitch ended.

The business was a success, but Phillips was restless. In 1974 he purchased a television antenna tower business. Growth was solid, but the too-frequent price hikes from his main supplier (Armco LP) became a burr under his saddle. A problem-solver as much as an entrepreneur, Phillips went the route of vertical integration: He purchased a couple of tube mills from a local facility and started making his own tube that he fashioned into antenna towers. For those in the know, this sounds like a daunting prospect of epic proportions. If he’d known what was ahead, he might have never gotten within purchasing distance of a tube mill.

No matter. Phillips persevered, and over the next several years, the business grew into a successful venture. However, things changed. Whether it was market saturation, the rise of cable television, or other market forces at work—or some combination thereof—the antenna tower business dried up. The hallmark of a successful entrepreneur is adaptability, and Phillips adapted by transitioning to other small-diameter, thin-wall applications

like automobile exhaust components. Phillips had reckoned that this market, which was already large, had excellent growth potential. Again, success came his way.

He wasn’t finished. Not by a long shot.

In the early 1990s he learned that his former antenna tubing supplier, was up for sale. He sensed an opportunity to repeat what he had done earlier—convert from residential antennas to automotive exhaust—and completed the purchase in 1993. This purchase would turn out to be much more challenging than the first.

“Armco agreed to a 90-day transition period with their current employees, who all went back to the mill after 90 days. He had to hire 60 people off the street and turn them into mill operators in that time,” said Angela Phillips, company president and Ralph’s daughter. Considering that it can take years of experience before a mill operator can work without assistance, it was a gutsy move. Despite the elder Phillips’ high hopes and confidence, Middletown made a lot of scrap, given the high demands of a full order book.

Figure 1

The Xiris WI2000 is suitable for outside diameters from 0.2 to 8 in. and a maximum weld bead width of 0.4 in.

“He said that he could have sent every one of his employees to medical school for the amount of money it cost him,” Phillips said.

Eventually the scrap rate fell, but mastering the technology is just one component of success. Keeping up with the automotive industry’s increasing demands is something else altogether. Because the supply chains are crowded and competitive, the margins are slim. Because product liability is high, the quality standards are ever-increasing. Doing well in this market is never easy, but rising to the many challenges is immensely satisfying, as Phillips has learned.

A Focus on Business Fundamentals

Running any business successfully is a matter of managing dozens of unrelated variables, and running a tube production company is no different. Staying on top of everything is nothing short of hair-raising. Steel prices can double or halve in a year, steel lead times can change without warning, and it’s a capital-intensive business. Liquidity is critical.

“Too many tube producers are too leveraged and can’t handle a jump in raw material prices,” Phillips said. Running inventory down in the closing weeks of every year is old hat, but running inventory up to compensate for a steel supplier’s scheduled shutdown takes educated guesswork and nerves of steel. Too much inventory chews up resources; too little leaves a company vulnerable to shortages. A heavy involvement in the automotive industry doesn’t help.

Still, the company has grown and diversified through the years. In the early 1990s, the company was highly focused on making exhaust components for the Big 3; these days it makes a much bigger variety of products, such as fuel system tubes; instrument panel support tubes; and components for heating systems. Its customers include the new domestics, and it makes some components for export to manufacturers in Europe and Asia.

Along the way, the company has learned to cut, form, and weld a larger variety of materials.

“Generic, cold-rolled tube is almost unheard of today,” Phillips said, referring specifically to the market for these products. “For this type of work, the predominant materials are high-strength, low-alloy steels, heat- and corrosion-resistant coatings, and both 300 and 400 series stainless steels.”

Other changes have taken place closer to home. For example, in 2014 the company instituted an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and went paperless. The members of the executive team knew that this was going to lead to big changes on the shop floor, and they were nervous about how well the mill operators and everyone else would accept the new system. The executives were well aware that its ERP program would be a success only if it were embraced by everyone who would use it. It turned out that many in the current generation of workers are more comfortable using digital technologies, and less reluctant to discard the traditional paper-based system, than the executive team realized.

“It wasn’t much of a concern,” Phillips said. “That experience taught us a lot about our workforce.”

A Focus on Mill Fundamentals

It’s the same story told for the umpteenth time.

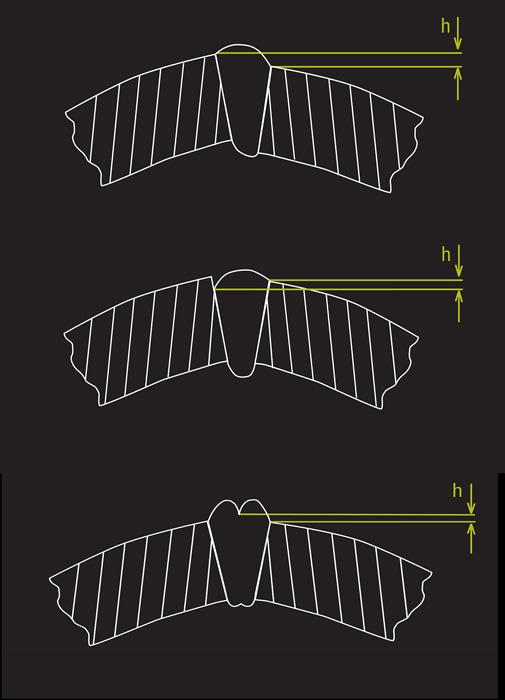

Figure 2

Laser-based measurement systems have two main strengths: the laser’s precision and measurement rate made possible by modern hardware and software. These strengths combine to provide an accurate view of the weld as it progresses, measuring characteristics such as edge mismatch, undercut, and freeze line (top to bottom).

“If a mill operator notices a problem and makes an adjustment, and it doesn’t solve the problem, he’s tempted to leave that setting alone and move on to make another, and then another, and then another, and pretty soon he has changed 10 settings,” Phillips said. “Then we have a shift change and the next operator makes a few more changes, and eventually the mill is totally out of whack.”

A focus on mill fundamentals is critical. Each component on the mill has a job to do. Making an adjustment is a matter of coaxing that component to do a little more or convincing it to do a little less, but each has its limits.

Even when the mill is aligned properly and all is running as well as can be expected, things happen. A mill is a big toolholder, and nearly all of the tools are in motion all of the time, and processes can drift over time. A process running outside its intended limits can turn into a disaster if it isn’t noticed in time.

“Failures in the field can be extremely costly,” Phillips said. “If we ship defective tube, we usually can narrow the defect down to a specific timeframe, but a potential recall usually encompasses a wider timeframe.” Many OEMs take no chances; when they come across a bad tube, they return the entire shipment.

“We had a case of making 11 bad tubes in a row valued at approximately $30, and the customer returned $65,000 worth of tube,” Phillips said. For components on the outside of the vehicle, the safety standards are much higher and returns are more costly. A shipment that included only a few inferior tubes can end up costing the company hundreds of thousands of dollars in containment in the field, sorting, reworking, and replacement.

In many cases, especially tube that undergoes severe fabrication, the weld usually is the Achilles’ heel. Many tube and pipe producers rely on an eddy current or ultrasonic system for flaw detection. Such a system introduces an electrical signal or a sound wave into the tube and monitors it as it flows through the steel. When the system detects a change in the normal flow, it interprets this as a defect and marks the tube accordingly.

The problem is that it’s difficult for a flaw detection system to provide 100 percent accuracy on a process that runs nearly 200 feet per minute. If the flaw detector is set to be too sensitive, it’s prone to false positives; if it’s not sensitive enough, flaws can slip past unnoticed. It’s a struggle to prevent scrapping good product and shipping bad product.

Then Middletown found a laser-based monitoring system that augments its flaw detection unit. Developed by Xiris, model WI2000 measures the edge alignment and weld bead dimensions and uses these dimensional measurements to create a view of the tube’s cross section as it exits the weld box, giving the mill operator a visual understanding of the weld box setup from inside (see Figure 1).

It is designed and programmed to alert the operator to defects such as mismatched edges, weld undercut, deflection (out-of-round tube), and roll (uncentered seam). It also monitors other weld bead dimensions that indicate flaws if they drift too far from average, such as height, ratio (the ratio between weld bead height and wall thickness), slope angle, and freeze line, which can be an indicator of a potential cold weld (see Figure 2). After a period of calibration, the system provides constant monitoring and feedback. When any of the parameters drift beyond preset thresholds, the system alerts the operator, but it doesn’t end there.

“It provides more benefit than we thought,” Phillips said. ”It has detected issues with gearboxes and setups that we would not have caught previously.”

Before using this diagnostic tool, setup was a matter of taking a large number of measurements, making the necessary settings, and checking the presentation at the weld area—and some of this was an art.

“Now it’s a science, and we are using it at both the Middletown and Shelby plants” Phillips said. If all the indicators on the system are in the green, the product is good. “After a setup, we no longer send a first sample for destructive testing by an offsite lab,” she said. “Now we can see any mismatch of the edges in real time.”

Because it monitors the tube’s dimensional characteristics, it provides insights about the mill’s alignment, the forming process, edge presentation at the weld box, and the weld process itself. It has helped troubleshoot problems on existing products and speed up the process of new product development. When a tube fails a destructive test, the new system provides troubleshooting clues.

“When we get a split seam, it could be due to any of 15 reasons,” Phillips said. “This system helps us home in on the right one.”

A Prescription for Scrap Reduction

How is the scrap rate these days? It’s not like it was in the 1994 timeframe, when the dollar value of the scrap would have mortified an entrepreneur with less fortitude than Ralph Phillips. Far from being enough to send an employee to medical school, the value of scrap generated by a new employee these days is about the cost of a semester at community college.

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI