Contributing editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Bending parts revolves around modeling software (video-enhanced)

Advanced software, training resolve skilled worker shortage

- By Kate Bachman

- August 6, 2018

- Article

- Bending and Forming

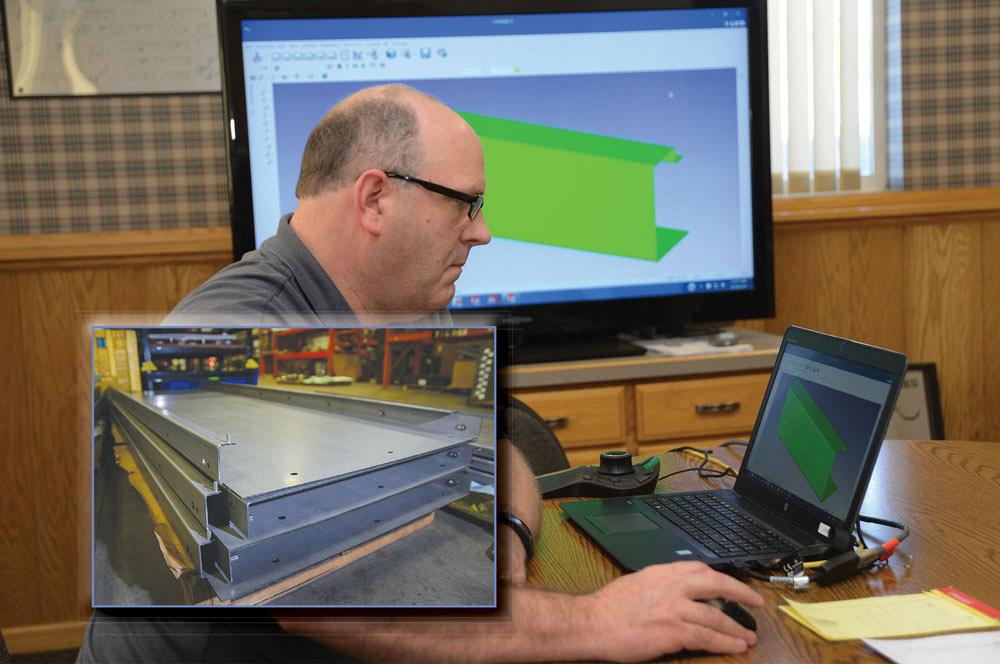

Dan Andersen, engineering/quality manager, used CADMAN modeling software to generate the cutting, forming, and inspection programs for a multibend part.

Minnesota fabricator Louis Industries is a bit of a dichotomy. It is at the epicenter of Paynesville’s Industrial Loop in a rural town of 2,432 people. En route to the 100,000-square-foot plant campus, you’ll pass a large, next-gen solar power field that the company fabricates parts for and acres of cornfields that have been planted and harvested for hundreds of years. It has sophisticated equipment and a workforce that is not composed of solidly experienced fabricators. A fair number of its employees are farmers whose schedules flex during planting or harvest season.

The third-generation manufacturer originated as a blacksmith shop making plowshares for the local farmers who grew food for the World War II war effort, and evolved into a $20 million metal fabrication job shop and metals service center (see Figure 1). Agriculture clients have long been its bread and butter, but the company also supplies multiple other industry segments, including power and energy, industrial equipment, outdoor recreation, packaging, home heating, and road construction.

Louis Industries has adapted and rolled with the changes out of necessity to survive a constantly blowing wind of change. It has spent years bending, leaning, evolving, contorting, and catering to the needs of its clientele, whether that be fabricating one-off pieces for a local farmer or a lot size of 10,000 for a FORTUNE® 500 OEM.

“Some of our customers have a high level of expertise; some of them don’t. We get prints drawn on bar napkins. We get prints drawn on old 2-D or AutoCAD. We get a prototype made with hand clamps and a torch in a garage. Whatever we get, we have to make work,” said Lance Louis, COO. “So that’s what makes us successful. We support all of our customers even if they don’t have advanced software to relay their designs.”

Firsts to Thirds

One way that Louis Industries has been successful is by keeping up with technology. It was one of the first U.S. manufacturers to buy a fiber laser and to install a solar array—at one time, the largest in the state (see Solar Components Producer, Solar Energy Consumer sidebar). It often is at the front of the line to buy the latest-model machinery introduced at FABTECH®. It recently has updated its press brake design that incorporates advanced modeling software to help it achieve first-time-good-part production.

“We try to stay at the forefront of technology,” CEO Leo Louis said.

Upgrading press brake part design software and educating its workforce and have empowered the company to meet the challenges it encounters.

Press Brake Modeling Software

The fabricator just made a sizable investment in upgrading its press brake forming area, with a new press brake and accompanying software, Lance said. “A part of that investment is in offline forming programming to take advantage of all the latest and greatest.”

Dan Andersen, engineering/quality manager at Louis Industries, said that forming increasingly complex parts on a press brake while shortening the time to bring a new press brake operator up to speed revolves around the forming software.

“What manufacturing is coming down to now is the model. Now we’re taking the SolidWorks® model, we’re creating the press brakes program from that, we’re creating the 2-D pattern for the laser to punch, and by the way, we’re taking the 3-D model and using it for inspections. We’re taking the model now and creating a print, the weld fixture, and we’re using it to communicate with the customer. So, it’s really become pivotal. Once you create the model, you can create inspection programs, 3-D offline robotic welding, even 3-D printing. We can make fixtures for go/no-go gauges with 3-D. So that’s where this is going.”

Figure 1

Leo Louis (left) is CEO, and his son, Lance Louis, is COO and part of the third-generation company leadership

Andersen said that LVD’s CADMAN® software has reduced one project from what would have taken four hours to engineer to half an hour.

Simulation Software

The simulation component of the software enables company engineers to try out the customer’s part program and detect any collisions or other errors before the job is sent to the shop floor.

“Before we got into this, that part design would have taken us four hours in the office to engineer, probably another two hours on the plant floor for our operator to write a program, and then probably hours of test bends to make it right,” Lance said. “Now we got it down to 30 minutes in the office and the first three parts we formed were good.”

Andersen demonstrated how the simulation software works. First, he set up a bending sequence to determine if a part is manufacturable at the press brake. Then he proceeded through the bends in sequence, and zoomed in or switched from a 2-D wire frame view to the 3-D view when necessary. But when he tried to make the final bend, the software sounded an alarm and halted the action because it detected a crash (see Figure 2).

“So I’m stepping it through the software. I’ve got the punch, I’ve got the die, the fingers, so what causes it not to work? Bend one: no problem. Bend two: no problem. Bend three: looking good. Now I hit bend four; Oh, here. You can see that this part is crashing into the press brake tooling. So, this part design is not usable.”

Based on the simulation, Andersen changed the sequence on the last bend by backstopping off of the other end. Then he stepped through the bending simulation again and the software let the entire sequence finish without sounding an alarm. “Now that it is clear, all I have to do is say, ‘Generate program.’ The press brake operators now have a manufacturable program and I can tell my salesperson, ‘Yes, we can make this part.’”

Previously an operator had to figure out if the part program was going to work through time-consuming trial and error.

Simulation catches errors in even the most sophisticated designs, especially those that occur as a result of model sharing, Andersen relayed.

“We got a model from a company in Europe. They designed the first and second angle; we designed the third angle. They did them in metric; we did them in metric. The challenge with European manufacturers is you have all these other measurements to worry about. In the U.S., a lot of our tool sets are in imperial units, so converting a European model to a model that’s usable over here is quite a challenge. Everything in Europe is designed in metric—tooling, material thicknesses … all of a sudden, you have left and right parts that are supposed to mate for welding that don’t fit together. The first time the customer put it in their weld fixture, we got the phone call. ‘What the heck did you make us?’”

Plug-in Software

Andersen said that the CADMAN software has a plug-in feature that allows engineers to patch in software code from a customer to expedite the design and to make sure it meets customer standards.

Figure 2

Andersen used CADMAN’s simulation capability to clear the bending sequences of potential collisions and other forming problems.

“Anyone who draws designs has their own nuances or tendencies. Or a customer company may have a standard corner that they use. With CADMAN B, we are able to plug their corner standard into our software program, and get that unfolded to a pattern faster. It’s really cool.”

Reference for Operators

The software upgrade allows operators to follow the programs on-screen at the machine, which simplifies and accelerates the bending, according to Press Brake Manager Andy Soine. Designs are now more manufacturable, Andy added.

“Ultimately, there’s very little we can’t figure out with the team that I have and our engineering department. There are ways to get it done,” Lance is great at saying, ‘Here, make sure it gets done and done right.’ And to our fault, we do. So then we do the next one.

“A lot of it is that you don’t need that much experience to generate a difficult part anymore,” Soine continued. “In the past it was all based on the experience of the press brake operator. So our ability to bend a part depended on whether the operator had done parts similar to it. That’s how the software has really helped us.”

Having the programming completed and vetted by the engineering department takes the pressure off the operators, he added. “Getting the right radius and making sure you’ve selected the right tooling for the job are huge issues. Now the engineers select the tool for the part in their designs. We don’t have to guess (see Figure 3).

The software has made the bending operation simpler to understand and quicker to perform. “Operators can view the monitor to see which finger angles to use. It answers the questions ‘Where do I load the part? How do I hold it? How do I rotate it?’” Soine relayed.

The operator can still make alterations. “If you don’t like it, you can move it around. You can look and see where the fingers are. You can see that it’s on a different finger set, how it’s positioned. This takes all the questions out of it,” Soine said.

Lance added, “I just don’t have many experienced operators who have been here for 10 years running a complex part. Now, with this software upgrade and offline programming, instead of an operator having to know 30 different things for a job, they’ll maybe only need to know 10.

“We’re trying to resolve our labor shortage instead of saying, ‘Oh my gosh, what do we do?’”

Complex Projects

Lance said that jobs have grown to be more complex, compounding already constrained workforce expertise (see Figure 4). As engineers understand more about what lasers can do, they’re designing more parts around laser cutting. “Customers may not want to use the old spurs and rectangles. They want fancier geometric shapes that are more appealing to a consumer or look better on a product. At the same time, they want us to design in efficiency. They want us to form something in one part versus making three parts and welding them together.”

Figure 3

Press brake operators like Patrick Klehr have the program to refer to at the press brake, which simplifies the operation by outlining which tool to use, which order to follow, and which radius settings to use.

One customer was literally welding nine components to make a bracket. “We now laser-cut and form the part in a way that eliminates all of the welds,” Lance said.

“So now we take their drawings and we can use our software to lay out what we need to do to form it. And we can even find errors in their drawings.”

Tighter Tolerances

Not only have customers’ parts become more complex, the tolerances required have gotten tighter as well, Andersen said, applying more pressure on the plant floor. He recalled that when a customer asked for tighter tolerances, he relayed those requirements to the production crew without comprehending how difficult that would be.

“I went out to the shop floor and said, ‘OK, we’re going to go from a tolerance of ±3/16 inch down to a ± /16 in. and then to ±1/32 in.’ That was a fun conversation. They said, ‘Are you kidding me! Why are you doing this to me?’

“With the software upgrades, we were able to achieve ±0.030 in. Once we understood that we could do ±1/16, we went down to ±1/32 in. And that’s the shop rule now.”

Modeling Software Eliminates Fault Finding

Lance said that one side benefit of the modeling software is that it eliminates the blame game when a part design doesn’t produce the part as expected. “Now, in the model, we can see where the error is. We can reproduce how we made it. We can say, ‘Oh, look, here’s the problem.’ The conversation changes from ‘It’s your fault’; ‘No, it’s your fault’; to ‘Let’s look at the model. So how do we fix this?’”

Look Ma, No More Prints

Andersen said that the software has rendered the design programs so accurate that one customer told him he no longer needs to provide prints. “He got to the point where he said, ‘Dan you can stop sending me prints. If you design it, I know I can make it.’ The technology has gotten to that level. So we can make designs, blanks, manufacture with more confidence.”

Lance added, “Using modeling software, we take the formed part drawing, flatten it, laser-cut the part, put it in the press brake, and form it to tolerances that we never hit before—and we do that on complex parts with four-plus bends by operators who may have little experience.”

Louis Industries, www.louisind.com

LVD/Strippit, www.lvdgroup.com

Figure 4

Advanced software has empowered the company to fulfill customer demands for part projects that have gotten more complex and with tighter tolerance over the years.

Photography by Mark Peterson.

Solar Components Producer, Solar Energy Consumer

Four years ago Louis Industries installed a 1,200-panel, 500-MW solar power array that produces upwards of 80 percent of its electricity.

“The state was doing this ‘made in Minnesota green energy initiative’ with solar,” CEO Leo Louis said. “And one of the guys doing our building addition said that because our roof is completely flat with no HVAC on it, it would be a good place for solar.” A solar company in Minnesota was looking for a flat roof on an industrial facility to install a solar array. “That’s how it started. As we dove into it, it made more and more sense,” Leo said.

At one time Louis was the largest private power producer in the state. “What’s so nice is that the data says last year we produced about 68 percent of the power we consumed with our solar.”

Some of the company’s customers have leveraged their initiative, he said. “They use it to say, ‘Our suppplier is green’ or ‘Our parts are green.’ That’s a little feather in their cap.”

The fabricator is manufacturing parts for a solar company as a result of being a solar energy user. The solar components are laser-cut and formed on a press brake.

“We’re seeing a renaissance of ‘made in the USA’ and knowing your supply chain. Is your supply chain doing everything right? Are they good stewards of the earth? Or are they polluting? In today’s society, people don’t want to work with companies that are questionable or shady,” said Lance Louis, COO.

“We’re trying to stabilize our expenses to hedge inflation long term, so financing solar made sense,” Leo added. “Our power is a huge cost for us. To have a stable price on power long term versus the average 3 percent annual cost increase of power every year will give us a huge advantage. So that was all part of the analysis.”

About the Author

Kate Bachman

815-381-1302

Kate Bachman is a contributing editor for The FABRICATOR editor. Bachman has more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor in the manufacturing and other industries.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI