Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Die Science: Metal bending basics on the stamping press, Part II

Achieving the desired bend angle through die design

- By Art Hedrick

- April 26, 2022

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Note: This is Part II of a two-part series looking at metal bending basics in a stamping press. Read Part I here.

One of the keys to getting the desired bend angle is to design the die so that it can be adjusted quickly, safely, and effectively to compensate for incoming material variability.

Coining the Radius

I remember being on the shop floor as a young tool and die apprentice, working on a die and trying diligently to get a simple 90-degree bend on a part. One of the older toolmakers told me that if I wanted to make a successful 90-degree bend, I would have to coin the radius. I asked him what coining was, and he said it was a way of setting the radius and bend angle by squeezing the metal in the radial area between the punch (or anvil, as he called it) and the die. I followed his instructions, and lo and behold, I ended up making the desired 90-degree bend.

At that point in my career, I understood that it worked, but not why it worked. Today, having about 40 more years of experience, I will explain why coining the radius works and how to achieve it.

No Strain, No Gain

To understand why coining works, you must understand what strain is and how it affects the final part shape. For a stamping to retain its shape with minimal springback, it must be adequately strained. This means you must form the metal in a way that imparts work hardening (also known as strain hardening) to adequately meet the metal’s yield point (the point of permanent plastic deformation) and eliminate springback. Permanent deformation is basically the product of work hardening.

There are two basic types of permanent strain: tensile strain and compressive strain. Tensile strain happens when the metal is stretched, and compressive strain happens when the metal is compressed or squeezed together. This process is commonly known as coining.

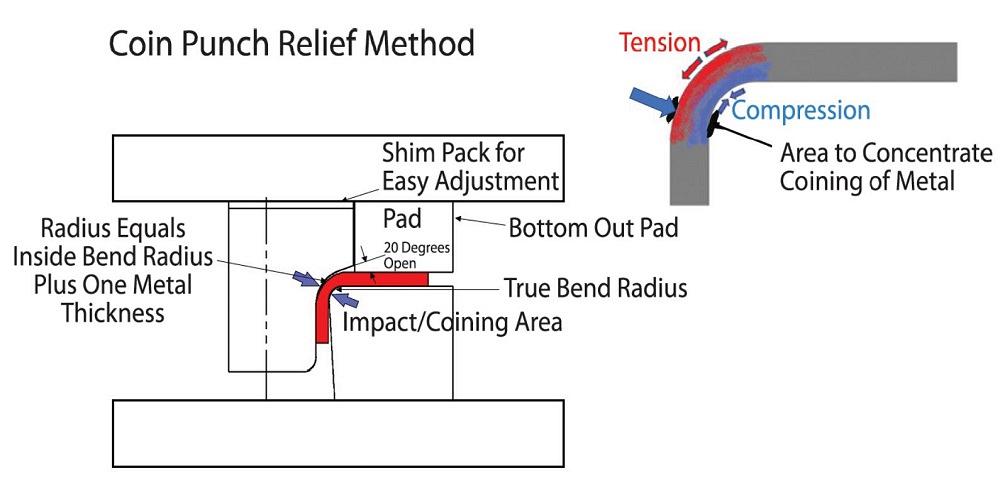

One of the more effective ways to create a 90-degree bend by coining is to design the die in such a way that the coining takes place in a small, localized area within the bend radius (see Figure 1). Coining the entire profile of the radius will help to reduce springback and achieve the necessary overbending. Keep in mind that using this method will increase the force or tonnage required to achieve the final desired bend angle.

The key is to impart compressive strain where it is the most effective, near the tangent closest to the metal being bent. By making the height of the forming block adjustable, you can change the final bend angle by shimming the forming section up or down. Doing so controls the amount and severity of the coining in the radial area.

Rotary Bending

Rotary, or rocker, benders are very effective mechanical methods for creating a given bend angle. Unlike coining dies, rotary benders create a great deal of tensile strain (on the outside radius) and compressive strain (on the inside radius) by overbending metal significantly beyond 90 degrees to an acute angle (see Figure 2). All of the strain is the product of naturally occurring straining that happens during the metal bending process.

These benders have many advantages. They can overbend the metal to as much as 30 degrees beyond 90. They are easily adjustable and can be used for bending up or down. Because they're essentially wrapping the material around the punch, the amount of force needed to create the bend is significantly lower than with the conventional wipe bending process. This is especially true when the wipe bending process uses coining as well. Rotary benders also can be designed with high-pressure nylon or plastic for bending prepainted materials.

One disadvantage of a rotary bender is that it uses mechanical motion to create the bend, so it requires periodic maintenance to ensure precise, low-friction rotation.

Die Design for Flexibility

There are at least half a dozen other ways to design a die to achieve the desired bend angle on a part, and all of them use both tensile and compressive strain. Sometimes the strain is natural, but sometimes the strain is created by additional coining.

Regardless of the method you choose, remember to design the bending process to allow for quick, safe adjustment within the boundaries of the press. This is especially true if the desired bend angle is very critical.

About the Author

Art Hedrick

10855 Simpson Drive West Private

Greenville, MI 48838

616-894-6855

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI