Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Navigating the design for manufacturing and industrial design worlds

DFM works best when it is part of the design team, not as an afterthought

- By Gerald Davis

- December 4, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

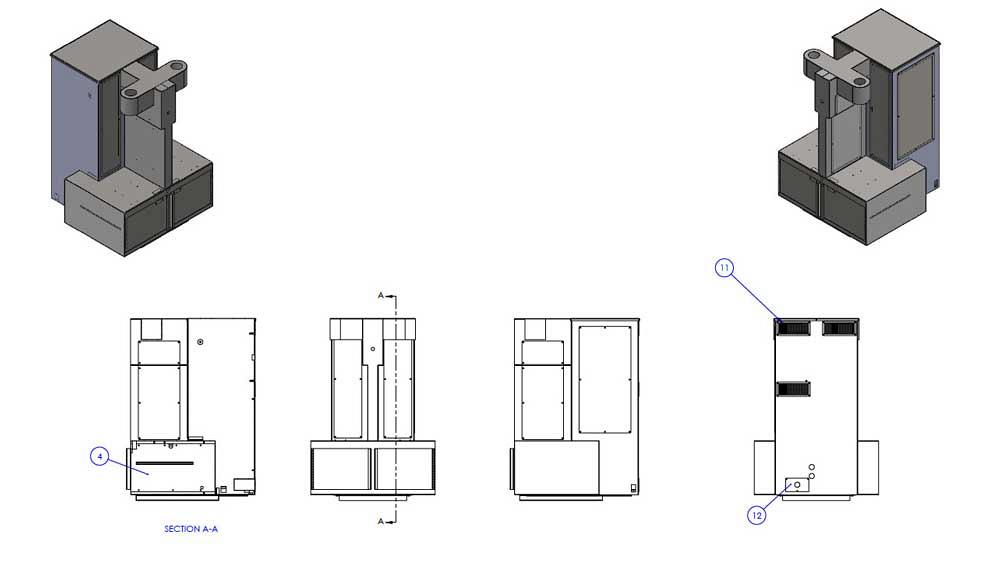

Figure 1

This is a preview of the design for manufacturing challenge that will be discussed in the January 2018 column: How to get this concept coffeemaker model ready for manufacturing.

Design for manufacturing (DFM) is an important part of product development. Fabricators have strong abilities in DFM, yet a common lament is that their wisdom is sought only after the “final” design has been found to be wanting.

In my precision sheet metal job shop experience, not many of the customers knew what to ask for with regard to DFM. They certainly knew they wanted great parts at a lower price. My shop didn’t volunteer much unless asked; we were not engineers. In retrospect, it would have been ideal to spend more time in meetings with my job shop customers as a member of their design team. With so many demands for time, it is a necessity to pick the battles that can be won.

Design Against Manufacturing?

Here’s a CAD Tip: Do not ever design against manufacturing.

By design for manufacturing, we’re talking about optimizing a design for a specific process. For example, injection molding is different from chemical milling, and both of those processes are different from additive manufacturing. All have a different impact on design.

The goal of DFM is to match a product’s function and demand with methods and materials that are best suited for fabrication. “Best suited” usually aspires to mean “most efficient” use of labor and material. Sometimes, schedule—that is to say cost of opportunity—might be defined best as “on hand.” For a DFM consultant, a moving target is something to expect and to embrace.

A typical DFM review meeting emphasizes rate of production and covers the what, why, when, and who. As a contrast, an industrial design (ID) review meeting has a different purpose and might focus on invention, inspiration, sensation, or perhaps ideal operation.

The “why” of the users’ experience is the result of decisions made by ID. We wryly note that ID is generally pleased with their work. (Thank you!) The decision to carve from billet or stamp from sheet is not something ID wants to own or perhaps even to discuss. However, DFM can’t make the decision without understanding ID’s overall goals for the product.

Business decisions about quantity and schedule for manufacturing are subject to change based on end users’ demands. The release of a new product requires some guesswork. Management is always conflicted by low unit price and no idle inventory; they want both. After agonizing over cash flow, management’s role in DFM is to set a target range on batch size and order frequency. Prevailing circumstances regarding material availability and utilization set the final batch size and shipping schedule.

DFM combines business decisions with design aspirations to come up with how it’s made. As a vital part of the development team, the purchasing department ultimately assigns “who” for the fabrication of the product.

Becoming a Team Player

DFM thrives with good understanding of the product’s intended function as well as its production schedule. Since launching my practice in 2004, I have worked as a DFM consultant on a variety of product development teams. Sometimes being a team player requires first being a team organizer. Roles depend upon the circumstances of the business. In all cases, my ability to incorporate suggestions from competing interests has led to success. I try to radiate positive attitude; I want to learn from the team what constitutes the ideal before any commitment is made to design.

By the same token, I don’t make idle suggestions. I’m prepared with facts and figures. If I said “wood,” it would reflect my considerations of the impact on function, aesthetic value, cost of ownership, and speed of distribution.

I’ve met a few industrial designers. Most are adept at delegation. That is to say, if someone else is responsible for resolving a detail, they will not interfere. However, if ID has taken ownership of a topic, then the utmost deference to their judgement is prudent. For example, if they want a chrome-like appearance, do not suggest wood as the first option.

The manufacturing department takes ownership of every detail on drawings. Like ID, they don’t like to have their stuff messed with. Their policies for revision control and document management are vital to the product’s successful life. As an example of policy, don’t change a design without changing the revision on the drawing. Don’t change the revision without permission. And, most importantly, don’t ignore their suggestions for change.

Ego and ID

DFM is a task with many masters. Most of them are able to clearly state their goals and measure results.

Here’s another CAD tip: To avoid problems with hurt feelings, use written statements of objectives, goals, and priorities that include plans for measuring results. To quote Adam Savage, former host of the TV show MythBusters, “If you don’t write it down, you’re just messing around.”

Part of the agenda for DFM review meetings is to evaluate the measured results and to adjust the design accordingly.

Manufacturing expects DFM to deliver designs that are easy to fabricate and assemble. The ultimate measurement scorecard is a schedule and budget that define the success or failure of the product. If the product is too expensive or is not available, then there are no sales.

As a player on the same team, ID is a standout in review. ID needs a result that satisfies tastes and ideals, which are often difficult to define and measure. I’ve enjoyed working with industrial designers who understand that manufacturing is the ultimate master and at the same time is able to bring art to the craft.

To those of you who have followed this column for the past dozen years, thank you. We’ve covered several oddities and delights in the CAD world. In 2018 we continue the theme of managing DFM and its friend the ID. Voga Coffee Inc. is going to allow us to use one of its coffee brewers as a case history in product development. It is a story of a new company with a trick of technology that transformed into a product.

Before Voga recruited me as their DFM consultant, the company formed a plan to buy a one-off product design (see Figure 1) that “represented a shop’s best practices.” The design presented for fabrication was a step file that showed the interior space they required for the product but did not show any seams or hardware. It was all up to the shop to figure out how to bend, weld, or bolt.

Surely this would result in the ultimate DFM, right? Especially if Voga bought one design from three different shops. Then they could pick the best of the best with practically no in-house investment in DFM effort. From there, they could consolidate their supplier network and go into production. They budgeted roughly $100,000 for each one-off design.

As a DFM consultant, would you have blessed this plan? Voga actually made this investment and assembled the three different machines.

What results do you predict? Hint: They hired me. Let’s meet for review next month.

Gerald would love for you to send him your comments and questions. You are not alone, and the problems you face often are shared by others. Share the grief, and perhaps we will all share in the joy of finding answers. Please send your questions and comments to dand@thefabricator.com.About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI