- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Prototyping system takes guesswork out of modeling custom header systems

Modeling system cuts development time, improves scavenging effect, boosts horsepower

- By Eric Lundin

- April 13, 2018

- Article

- Shop Management

At 16 years old, Jeff Correia learned a difficult and expensive lesson about automobile repair work.

“It was my first car, a Honda Civic SI,” he said. “I added a turbocharger to it, blew it up, and paid a mechanic $1,600 to rebuild it.” To his horror, the engine blew the next day, and he wasn’t about to put up another $1,600 for another rebuild. Although he knew that tearing down and rebuilding an engine would be a monumental task, he figured it wasn’t beyond his reach. He knew a bit about engines from years of tuning and maintaining quads and dirt bikes with a group of like-minded friends.

“I found a new motor, a head, and a transmission, and I got to work,” he said. That experience paved the way to Street to Strip Auto Design, a business he runs with Wes Vogt, one of the group of friends he grew up with.

A Journey of a Thousand Miles

Correia didn’t go straight from a rebuild to opening his own shop. After finishing high school, he and longtime friend Stephen

Bond ran a powder-coating business out of his parents’ garage while working his way through Manhattan College, and later branched out to changing clutches and other repairs. Around the time he completed an engineering degree, in 2012, he teamed up with his brother Eric, Vogt, and Bond to lease some commercial space to expand the business. A couple of years later they invested in a gas tungsten arc welder and the business changed direction, focusing on high-performance fabrication.

“A typical project involves a customer who recently had an engine rebuilt and installed, and he wants a complete performance package–a turbocharger, custom exhaust headers, high-performance fuel pumps, and an aftermarket fuel cell,” Correia said.

To handle the additional heat generated by the engine, the cooling system typically needs a larger or additional radiator, and to deliver the best performance, a turbocharger needs an intercooler. Although intercoolers are commercially available, most intercoolers for high-performance applications are custom designed for that specific model car.

Some automobile enthusiasts take it a little further than others, asking for the cleanest possible engine compartment. In some cases, this means going so far as to “shave” the engine bay, which involves welding patches to cover unnecessary holes and respraying the bay. It also involves moving the brake system’s proportion valve to a new location, usually behind the firewall, and routing the brake lines so they’re hidden from view. In other words, a project like this can be a lot of work, or it can be even more work, depending on the customer.

Building an intercooler, planning the locations for the fuel pumps, moving a component or two to accommodate a larger radiator, and working with any other requests leads to fabricating all of the necessary brackets, hangers, and miscellaneous hardware from scratch. In other words, this is a fabricator’s dream come true. Every job is unique, every job has specific challenges, and every job requires a combination of mental gymnastics and fabrication savvy to locate every component without interference and to bring it all together successfully.

Hanging Hopes on Bent Wire

Working up an intercooler design or bending brake lines is one thing; designing a complex assembly of several parts is something else altogether. For nearly every custom automotive shop, designing an exhaust system is a monumental headache.

Step1

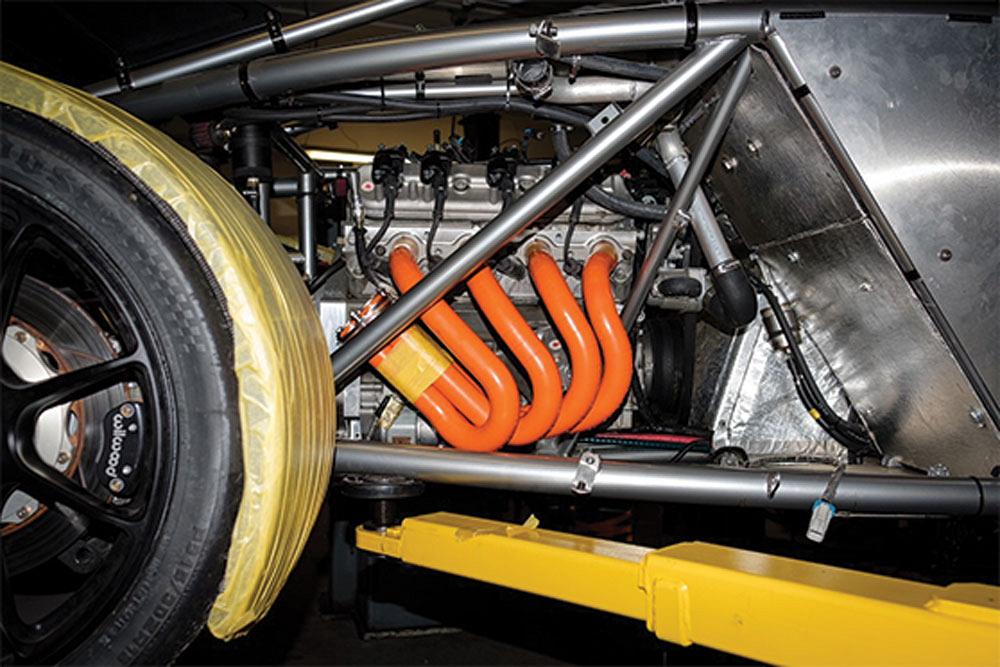

Use the icengineworks® modeling blocks, which are shaped in bend radii that match commonly available U-bends provided by established vendors, to create an exhaust header tailored to the specific needs of the project.

“Designing an automotive piping system, whether it’s a turbo manifold or a header, is brutal!” Correia said. “You have to estimate the collector’s location, then you try to get one runner to the collector and join them. At that point, the collector is supported.” Even with the collector in a fixed location, the rest of the project doesn’t get much easier or go much faster.

The traditional tool for figuring out the routing is a series of stiff wires, usually coat hangers, bent by hand and using anything handy, often using scrap pieces of bent tubing, to help estimate bends needed. After running each one to the collector, the fabricator has a representation of each pipe’s route, but it’s very crude and only vaguely accurate. From there, it’s a matter of converting wire to tube. This step isn’t quite as crude, but it’s still burdened with a lot of guesswork.

“You buy U-bends that were made on a mandrel bender, which come in many in different centerline radii, but you have to guess at each bend radius to clear any obstructions,” he said. The next step is cutting the U-bend on a band saw, and this too is a source of frustration. The cut might be too long, too short, or at the wrong angle, which makes good fit-up difficult or impossible. Some pieces can be saved by sanding them to the right contour, but many have to be scrapped at this point.Oh, one more thing. An ideal header system has runners of equal lengths. When the exhaust from cylinders 1, 2, 3, and 4 travels a uniform distance through each pipe to the collector, each burst of exhaust arrives at the collector in a timed sequence. They don’t interfere with each other, which optimizes flow and minimizes the back pressure, which steals horsepower. The system also can induce resonance, which enhances scavenging, by having the pressure waves inside the tube oscillate between positive and negative and timing them appropriately. The fabricator accomplishes this by calculating the runner’s length while keeping in mind a specific engine speed, measured in revolutions per minute.

“You have to make a lot of educated guesses,” Correia said. “You hope you have equal lengths, you hope everything lines up well, and you hope you have enough room to weld everything together.” While the main goal is to maximize horsepower, many customers have a secondary goal: They want a system that looks great, too.

“I must have changed one system 20 times,” Correia said, referring to one particularly vexing project.

“Designing a system like this is a creative process, which is enjoyable, but all the necessary tweaking and adjusting drives a person nuts,” he said. “Making a header system shouldn’t be a battle of fit-up,” he said.

Building a Better System, Block by Block

Eventually Correia and Vogt discovered a better way.

A modeling system developed by Victor Franco, founder of icengineworks®, enables fabricators to make a full-scale prototype that takes all of these factors into consideration before they cut a single pipe.

An automotive enthusiast himself, Franco got involved in tuning cars in the 1980s. Like many hot rodders, he learned from many sources—reading, doing, and talking to other fabricators—and he was baffled to learn from other enthusiasts that nobody had developed a system for prototyping tubular assemblies for exhaust systems. Bending a coat hanger by hand sounds like it’s straight out of the Stone Age, relative to all the other tools most fabricators have at their disposal.

Step 2

Verify the fit-up, installation sequence, and clearance with other components in the engine bay. The modeling system provides a full-scale representation of the header.

The modeling system comprises lengths of plastic tube, straights and bends, that snap together. The diameters, bend angles, and bend radii of the bent lengths are identical to the bends that exhaust system builders typically purchase for this purpose. The fabricator builds each runner, one block at a time, which equates to one inch at a time, and checks the fit to see if it interferes with anything under the hood. As long as he locates and secures a collector (or a dummy collector) in the right location, thereby establishing a target to shoot for, he can get the geometry right. From there, it’s a matter of building three more runners, making each the same length as the first, which is as simple as counting the blocks to ensure that each runner has the same number of them.

The second tool, a cutting system, is a fixture that works with most band saws. The user secures a U-bend and the corresponding cutting spacer to the fixture, aligns it with the saw blade, and makes the cut. The last tool is a clamp developed specifically for this system. The clamp allows the user to get the two pipes aligned and secured for tack welding. Several clamps can be used to create more complex runners made of several metal sections that can be tacked all at once.

In Correia’s experience, the system eliminates the guesswork, rework, and scrap.

First is the guesswork. Long gone are the days of making a model out of bent wire. Using a wire 3⁄16 inch in diameter to represent tubes that measure 3 in. dia. always left a lot to be desired.

“The modeling system makes the design come to life,” Correia said. It provides a complete model, to scale, that accurately represents every bend in the proper orientation and every straight length in the proper place, so the fabricator knows exactly what he needs to do.

“You have a road map right in front of you,” Correia said.

Second is rework, which can be severely taxing to a fabricator’s patience.

Coupled with estimating the routings in the first place, which puts a strain on the fabricator’s concentration, rework is just a little worse, and both chew up a lot of time.

“There’s no comparison in the amount of time it takes to build a header system,” Correia said. “When using the modeling system, it takes about one-quarter of the time,” he said. “The ability to change the design on the fly is second to none. It allows continuous small adjustments, helping to reach a perfect design, one that combines beauty and performance.”

Finally, eliminating reworking the tubular material leads to another means of savings.

“Before I found this system, I generated piles of useless scrap,” Correia said. “No matter how good you are, you can’t do as well without this system. You save money on material because you don’t waste any. The system is almost priceless.”

Street to Strip Auto Design, www.stsautodesign.com

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI