Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Solving manufacturing problems from the ground up through process management

Why it's vital to understand where the work gets done and trust people on the shop floor

- By Lincoln Brunner

- October 26, 2022

- Article

- Shop Management

Standing in a repair shipyard in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1974, inspecting the shattered bottom end bearing of a 30,000-HP diesel engine, engineer Paul Vragel knew he had a problem—several, actually.

The hobbled engine powered a ship that was in Lisbon for its guarantee drydocking and inspection. The ship, owned by Vragel’s multinational oil company employer, and the engine both were built in Spain. Vragel’s employer had a contract with the company that built the ship, but not the one that built the engine—which was constructed under license from a Danish company. The repair shipyard was charging the company $30,000 a day (about $250,000 in today’s dollars) to dock the ship there, adding to the urgency.

And now, with the ship in drydock in Portugal, neither the Spanish nor the Danish were taking responsibility for that shattered bearing.

The then 23-year-old Vragel—sent to Lisbon as an “observer,” but with orders to fix the bearing problem—had no situational knowledge or budget to draw upon. He also had no staff and no authority.

He also didn’t speak a lick of Portuguese. Or Spanish. Or Danish, for that matter.

“I’ve got nothing,” Vragel remembered thinking. “I’ve got no domain expertise, no authority, no cooperation. Flat. Zero. Except, I figured, ‘OK, I’m here.’ So, I said, ‘I want to go and look at how they make the bearings.’”

Look he did. In a couple of days, he discovered the problem: The manufacturing process produced porosity in the bearing metal, and the bearing was failing under stress. But Vragel knew, even at 23, that unless the people who cast the bearings recognized how their process connected to everything else in the chain of events that led to the breakage, nothing would get fixed.

Wisely, he decided simply to ask questions of the bearing makers, listen, and then sketch out the process with pencil and paper.

“Out of that, if they can see where this is going, then they can connect the things that they know to that [sketch],” Vragel said, the memory still so fresh that he talked about it in present tense. “I look and listen and work with the employees. In a couple of weeks, we take what they’re doing, look at the process, and fix the process. Now they can make perfectly acceptable bearings.

“That was very interesting,” he added. “I’m 23—no authority, no domain knowledge, no staff, no budget, cross-language, cross-culture, in a plant overseas that I have never seen before. And in a few weeks of listening, we get a permanent increase in their manufacturing capability—that they own.”

The engine got fixed, the ship went back into service, and Vragel earned his stripes using nothing more than a willingness to observe, discern, and help the people doing the work connect the proper dots.

The Process Is the Problem, and Employees Know How to Fix It

Graduating from helpless to hero in Lisbon taught Vragel something: to see for himself how things get done on the floor—and more important, to listen to the people doing it. It led him to two conclusions about manufacturing process management that he’s carried with him ever since:

- Employees are the world’s experts at knowing what they actually do every day.

- Ninety percent of the issues that waste time and money and produce poor results are embedded in how a company’s processes actually work (which usually differs from how they’re expected to work or how they’re documented).

Listening and Doing

Vragel makes a point of walking into a client’s factory and hearing from those who do the work first, primarily because they invariably give him the real story—the most valuable information there is. Vragel has seen this truth affirmed over and over—first during his 12 years working for that petroleum company and now as a consultant to manufacturers.

“We start with what you actually do,” Vragel recalled telling a Tier 1 automotive supplier that hired him to rescue the company from a pinch. “We’re going to visually lay it out, the whole company, so we can see how everything really works. And the people who know that are the people who actually do it.”

The auto supplier needed to secure a particular certification in three and a half months or it would lose its ability to get new business. To make matters more interesting, the company’s quality manager had recently moved to a different division within the corporation, and its chief engineer was on medical leave.

Worst of all, the company had done nothing to prepare for the certification. And for background, the company gave him a pair of 3.5-in.-thick binders full of stuff that documented what the company thought it was doing—but actually wasn’t. Vragel read them and then ignored them.

“I don’t really care what your existing documentation is,” he said. “I care what is really happening.”

So, Vragel and a company team sat down and visually captured what the company was actually doing. In 30 days, they had identified every process within the business and then fixed more than 75 items the team identified “We didn’t make lists of stuff we were fixing—we just fixed it,” Vragel said. “Don’t talk about it. Don’t make a list. Implement. Implementation starts on day one.”

Sand in the Gears

“All you have to do in our culture is say the word problem, and little hairs on the back of the head start standing up, because problems have owners, and then there is a search for the guilty,” Vragel said. “We want to avoid triggering this response and resistance, but we’re going to have problems that we need to talk about.”

But how does a consultant get people to open up about issues? By making it clear that the problems belong to everyone—a concept Vragel calls sand in the gears.

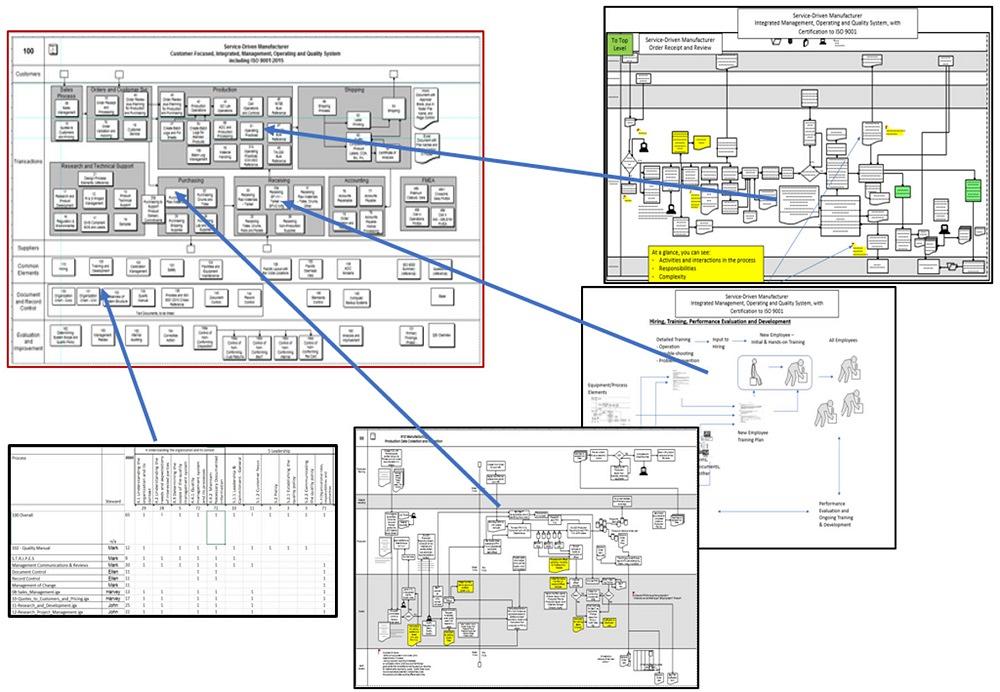

Drawing up charts like these helps Vragel present a company’s processes in a way that helps employees visualize the problems at hand and come up with solutions themselves. Paul Vragel

“Sand in the gears—sounds bad,” he said. “OK, ‘sounds bad’ is different from, ‘search for the guilty.’ If you say, ‘Where are the problems?’ lips are zipped. If you say, ‘So, if we had some sand in the gears, what might you say about that?’ [the response] comes quickly because they’re dealing with that every day.

“Now we have the process laid out—we know where the sand in the gears is, from the people who actually do it.”

No-fault Assurance

Vragel makes it clear to employees up front that he’s not there to identify low performers or get anyone fired. Rather, he’s there to help improve productivity and grow the company. That kind of reassurance matters.

“Get the buy-in first. That gives you access to this wealth of information and willingness to share it.”

Reassuring employees at the Tier 1 auto supplier that their input was valuable and demonstrating by action that they were safe to share it translated to buy-in. That buy-in led to identifying another 75 items that employees wanted to fix—and did—while Vragel was still there.

The company ended up landing its certification, albeit a bit late. But the overall results surprised everyone: Within six months, the company recorded a 30% increase in earnings with no layoffs and no increase in sales.

And within 12 months, the company pursued and landed its first-ever business with Toyota.

“It’s usually a five-year experience,” Vragel said. “Toyota came in, looked at what they were doing, and said, ‘Good.’”

Turning Cynics Into Converts

Vragel noted one final thing about the inevitable naysayers: With virtually every change process, cynics in the back of the room—burned by the failure of other initiatives in the past—fold their arms and grumble, “We’ll see about that.”

That’s exactly what happened to Vragel during one client meeting years ago. The employee’s main point was that nothing the company did previously to solve the issues at hand had worked. And he was right. But then …

“We’re working with the whole [place], everybody who’s there, and in two weeks, we identify and pretty much resolve something he’s been working on for two years,” Vragel said. “I did not need to say anything. He became a convert. There’s nothing like a convert.

“As it turns out, this is replicable across other businesses. I don’t know up front who they are, but someone is going to get this and be a convert and support others in the whole effort of developing an environment safe for change.”

In fact, it worked that way at the Tier 1 auto supplier too.

“The production managers in this three-shift operation stopped going out for a smoke on their breaks,” Vragel recalled. “They would come and talk to me about process improvement. These are the guys who are [usually] fighting against changing anything, and they’re coming in, wanting to see, ‘OK, here’s what we’re running into. What can we do here?’”

And if those managers end up looking like heroes, no worries, Vragel said—that’s all part of the intent.

“I’m fine with that, absolutely fine,” he said. “They’re delighted. They’re happy that they’re now able to do things they could never do before.”

About the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI