- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Plasma process powers up productivity for pressure-vessel provider

Gas plant provider benefits from plasma cutting, beveling capability

- By Eric Lundin

- January 22, 2019

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

Discovered thousands of years ago, natural gas has been used commercially for more than 200 years. Used primarily as a source of light throughout the 19th century, it became a heat source when the Bunsen burner was invented in 1885, and in the modern era has additional uses. It has an important place in electricity generation, plays a critical role as a feedstock for many industrial processes, and is a viable fuel for transportation.

Formed underground over millennia and a byproduct of plant and animal matter decomposition, natural gas often isn’t ready for use in its natural state. Just as crude oil requires a refining process to turn it into a useful resource, natural gas requires processing to turn it into a marketable product. Two chief considerations are the moisture level and CO2 content, both of which are removed by a process well known to RAMA Fabrication Inc., Odessa, Texas. The company fabricates steel to build processing equipment, specifically ASME-code pressure vessels and related system components, to build dehydrators that it sells to natural gas processors. The company also is a subcontractor of this service, using its own dehydration equipment to process natural gas for gas providers.

In business since 1980, RAMA joined forces with Interstate Treating Inc. in 1990, a move that added construction expertise. The companies’ work is in line with the advice of architect Daniel Burnham: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood.” Together, the two companies make big plans, the sort that have more than enough magic to make hearts race: They design and build entire plants, turnkey, that can process up to 650 million standard cubic feet per day of natural gas.

The two companies’ success is a culmination of optimizing every process under their collective roof, from how quickly Interstate can design a plant to how efficiently RAMA can cut, bevel, and weld steel.

Insights, Initiatives, and Investments

“To make pressure vessels and other components, we process pipe from 12 inches to 120 inches in diameter, anywhere from 10 feet to 100 feet long,” said Manufacturing Supervisor Matthew Elrod.

“We build systems for midstream operators—these are processors that dehydrate the gas and remove the carbon dioxide, then send it to the pipelines,” he said.

Elrod has more than 25 years of experience in metal fabrication, some of it dealing with robotics, and he knows a progressive company when he sees one.

“This company is big in making investments and is a leading fabricator in west Texas,” he said. This doesn’t mean that the company never encounters a problem. Like every manufacturer, it encounters an occasional headache. The difference between progressing and languishing is in how quickly the company recognizes the problem and how effectively it deals with it. In the case of RAMA, it found that relying on some of its vendors was a small but growing problem.

For many years the company purchased the cylinders it needed to build dehydrator systems. When it received the cylinders, RAMA did the rest, adding heads, nozzles, and piping. However, the cylinder deliveries weren’t always timely. As is the case for many items, purchasing meant waiting.

“The cylinders were one of the longest-lead-time items we purchased,” Elrod said.

The first step in making a shell for a pressure vessel is bending steel plate to the correct radius. RAMA Fabrication Inc., Odessa, Texas, selected a rolling machine from Italian manufacturer DAVI.

The company wanted to make its own cylinders, but it didn’t have the equipment to do it. It had no way to roll steel plate to make a cylinder, and because it relied on manual processes for fitting pipe, it had no fast, consistent way to make double bevels and other critical features. It also meant that, as the general contractor, Interstate had to hire subcontractors and audit them for quality. Working with subcontractors isn’t necessarily bad, but it adds layers of complexity, making the construction process more cumbersome and time-consuming.

The net result was that Interstate wasn’t as responsive to market demands as it wanted to be. Occasionally a project would be completed after the deadline, and once in a while a client would ask Interstate some frank questions, which led the RAMA management team to look at its processes and ask itself a few more. One of them was as straightforward as the answer.

Should the duo wait on vendors to deliver cylinders? No.

Processing Pipe with Plasma on the West Texas Plains

In Elrod’s mind, the quest to find the best machines for RAMA’s needs was a two-pronged proposition: find the right equipment and find the right vendor. Savvy about the business of fabrication as much as fabrication itself, Elrod knows that a trustworthy and reliable vendor is a partner, and a partner is invaluable.

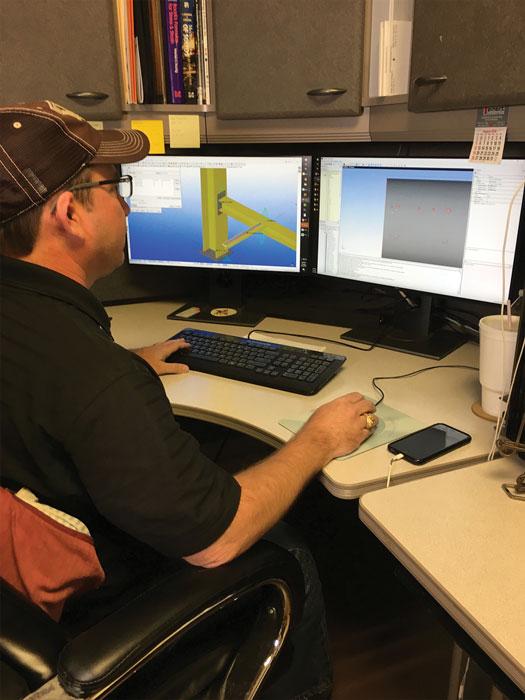

When RAMA began searching for machines to form cylinder shells and cut the domed caps, it didn’t start from scratch. The company had been using a plasma machine, model RPC 1200 from HGG, for cutting long products such as beams. That machine already had helped RAMA’s bottom line—its software catches errors before they get to the shop floor, and it nests parts to maximize material yield, Elrod said. Elrod was impressed with the machine and its service personnel.

“They respond to service calls faster than many other manufacturers,” he said, adding that the service personnel seem to know the equipment better than those in many other equipment builders’ service departments. Elrod made a trip to visit the company’s location in the Netherlands and found that the company culture reminded him of the culture of Interstate and RAMA.

“I saw the plant, and I was impressed with the processes, so it seemed like a good fit,” he said.

HGG understands that it’s not in the equipment-building business, but rather the problem-solving business, and hardware alone doesn’t solve problems. Hardware needs software, and about 30 percent of the company’s workforce are software engineers. The idea is to develop software that runs the machine so capably that the user doesn’t need to do much in the way of programming. After the machine imports the drawing, an onboard laser measures the workpiece’s dimensions, and the software develops cut paths based on those dimensions—the machine operator doesn’t have to compensate for tube or pipe that is out of specification in roundness, straightness, or other characteristics.

HGG’s goal is to provide as much programming as possible; it strives to make its machines no more difficult to operate than a telephone. The operator still can intervene if necessary, but the manufacturer understands that programming time cuts into uptime, so its goal is to make operator intervention unnecessary and keep the green-light time as high as possible. The company also knows that it needs to offer more than a portfolio of standard machines, so it builds custom machines when necessary.

While every equipment builder’s goal is to see the equipment, and the processes it performs, through its customers’ eyes, HGG has more insight than most. The company provides fabrication services using its own equipment, so it doesn’t just talk the talk—it is well practiced in walking the walk as well.

While parts drawn in CAD are dimensionally perfect, the processes used in metal fabrication have to reflect imperfect dimensions. HGG’s plasma cutting machines measure each workpiece before cutting, so the cutting 0head follows the part’s actual contours for precise, consistent cuts.

Ultimately RAMA purchased two machines from two vendors: a machine from DAVI for rolling plate to make cylinder shells, and a plasma cutting machine from HGG for beveling cylinder caps.

The plasma cutter, a custom machine based on HGG’s model SPC 3000, handles materials from 0.375 to 4.5 in. thick. The supplier modified the machine in two ways. First, it modified the machine’s layout to match the space available on the shop floor. Second, it modified the software, developing subroutines, or macros, specific to RAMA’s applications.

Throughput and More

Interstate now uses fewer subcontractors, eliminating some of the bureaucracy at the job site, reducing both the time and cost needed to build a plant. And, while bringing the vessel-making processes in-house has helped RAMA meet deadlines, it has done much more for the company.

In the old days, RAMA needed five to six days to make a pressure vessel, and it was limited to simple bevels. With the new equipment in place, it can turn out a pressure vessel in about one day, according to Elrod, and it can do the complex bevels—X and K bevels—that are necessary. The change in throughput was so dramatic that RAMA has changed its cost estimates, delivery times, and even its client base. That is, its turnaround time on pressure vessels is so short that RAMA’s processing line has some spare capacity, so the company uses the excess machine time for some subcontracting work that it does for other fabricators in the area.

It also changed the way RAMA searches for new employees.

“Welders are hard to find, but now we need fewer of them,” he said. In the past, welders would cut, bevel, and weld, but the new machines’ throughput is so fast that the welders no longer are involved in cutting and beveling—they focus on their core skill only. It’s this focus on welding that has relieved some of the pressure on finding additional welders.

At the same time, the welders’ time is used more efficiently. Because the current processes are based on machines’ capabilities, and not manual processes, the materials sent to the welding stations are cut and beveled with much more consistency than in the old days. The welders no longer have to compensate for inconsistent part fitup.

“We cut the welding time in half,” Elrod said.

How did this play out in building entire dehydrator plants? The impact was substantial.

“We’ve seen a 25 percent improvement in costs and delivery time,” Elrod said. “These days, we can complete the fabrication portion of a new plant in about two-thirds of the time of some of our competitors.”

RAMA’s plasma machine, a custom-made unit based on HGG’s model SPC 3000, can be changed over quickly from oxyfuel for thick sections to plasma for thin sections.

HGG, www.hgg-group.com

Interstate Treating Inc., www.intertreat.com

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI