- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Using a single machine to drill, thread, polish for making tube and pipe preparations the lean way

Programmability, 20-tool library open up fabrication possibilities for manufacturing and plumbing applications

- By Eric Lundin

- March 13, 2018

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

For anyone who has embraced lean manufacturing, it’s unlikely that any phrase causes more angst than batch processing. The notion of performing several steps on several machines, each requiring some amount of setup—interspersed with loading, unloading, and moving materials from place to place—is the antithesis of the one-piece flow that lean manufacturing strives to achieve.

Derived largely from the Toyota Production System, lean manufacturing works relentlessly to remove any non-value-added activities from a process, ensure that workpieces—raw materials, intermediate goods, and purchased components—are where they need to be when they need to be there, and create a streamlined and smooth-flowing process.

The ultimate lean process is a matter of loading raw material into a machine and unloading a finished assembly from the same machine. Although for most products this notion is preposterous, for some fabricators, it is a reality.

Pulling a T

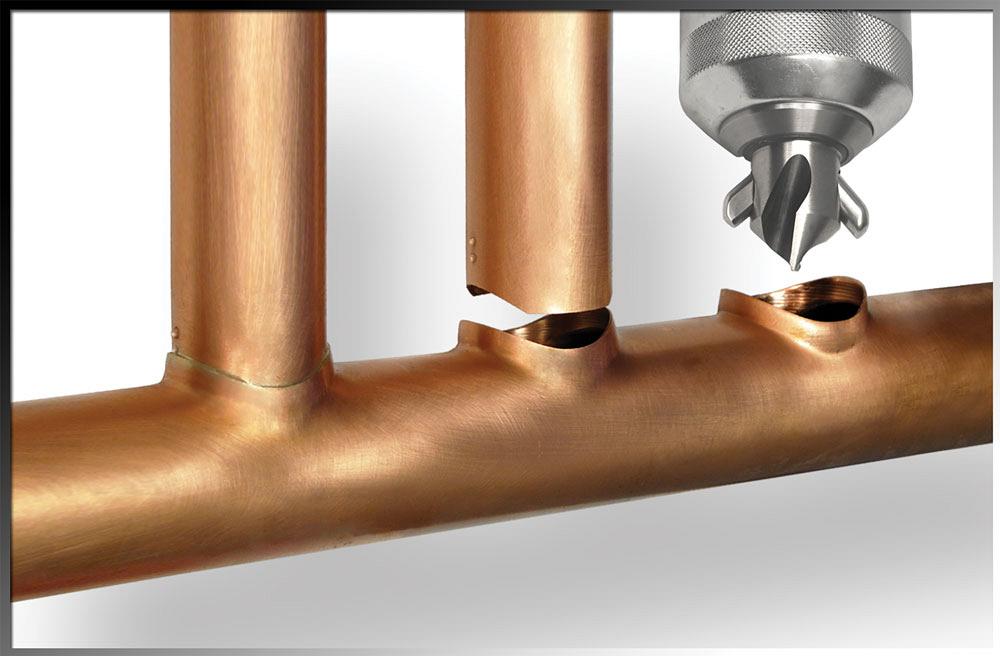

At its simplest, the method for preparing pipes to make a plumbing subassembly uses at least two machines—one for cutting and another for forming collars, or Ts. While cutting the pipe to length normally is done on a band saw, drilling the hole and creating the T flange can be done with a portable tool (see Figure 1).

T-Drill developed hand-held tools and bits specifically for this application. Hand-held kits include the T-35 and T-65, which make Ts from 1⁄2 to 1¼ inch diameter on pipe from 5⁄8 to 2-5⁄8 outside diameter (OD) and Ts from ½ to 2 in. dia. on pipe from 5⁄8 to 4-1⁄8 in. OD, respectively. In addition to hand tools, it also makes collaring machines, such as the model S-54, which has quite a bit in common with an auto-feed drill press.

It’s a single-station machine that makes collars from ¼ to 2-1⁄8 in. dia. on pipe from 5⁄16 to 4-1⁄8 in. OD. The machine operator loads one pipe at a time, positions it manually, then locks the pipe in place and operates the unit much like a drill press operator.

In keeping up with changing times, the company expanded its product offering to include a programmable machine with an automatic feed table. After installing the collaring head, programming the rotary and linear T locations, and loading a tube into the machine—that is, one setup—the operator starts the program and the machine takes it from there, processing the manifold. This was a big improvement over its basic machines, but more was yet to come.

An Automation Situation

“T-Drill got a call from the plumbing operations manager at a big mechanical contractor,” said Carroll Stokes, sales manager for T-Drill. “He had a vision for a process, one that would move large amounts of pipe quickly. The cutting machine would be fed from a preloaded rack, so when the rack was empty, the machine wouldn’t be idle for long—it was just a matter of swapping out the empty rack for a full one. From the cutting machine, the pipe lengths would be fed to a second machine that would drill the holes and pull the Ts. Later on, he came up with a few more bells and whistles. The machine needed to apply quick-response (QR) codes to each pipe, and a programmable diverter table would segregate the parts as they were finished.”

A collaring head performs two functions, drilling and collaring (right). When drilling, the bit looks like a common drill bit. After drilling a hole, the machine operator rotates the drill bit’s collar to extend two forming pins, then starts the drill again and retracts the bit from the hole, which pulls some of the surrounding material out of the hole to form a collar. The flange is then ready for mating to an intersecting pipe (center) and joining (left).

The machine would be programmable, but not programmed by an operator. It would simply receive instructions straight from a database in comma-separated values (CSV) format. Because this particular construction firm did a lot of multiresidence construction projects, often buildings with thousands of units, it needed a machine flexible enough in its control system to handle thousands of unique parts.

None of this posed any sort of a problem at T-Drill. The company had a long history of making custom machines, and it had enough experience in material handling to develop such a system, but this request was unusual. First, in T-Drill’s experience, requests for custom machines came from manufacturers, not from plumbing shops. Granted, it was a big plumbing shop, but it was unusual nonetheless. Second, the company was accustomed to developing machines that made a few unique parts thousands of times; programming for thousands of unique parts, and working with a control system complex enough to handle this, was new to T-Drill.

The T-Drill staff would come to learn that, because this firm—J.C. Cannistraro—was so large, and because the construction industry was changing, this particular plumbing shop was changing, too. It had an interest in doing as much prep work in its own shop as possible. Rather than send pipe to the construction site, it wanted to send subassemblies to the construction site. In other words, it was starting to work more like a fabrication shop, and ultimately it would work like a manufacturer. A lean manufacturer.

You Can CAD, Can’t You? Every fabricator and every manufacturer understands computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM)—most couldn’t function without them—and in the construction industry, the reigning program that contractors use to visualize and plan is a similar product: building information modeling (BIM) software. Before starting on a plumbing project, the contractor knows what the project entails: how many feet of pipe it needs and the number of Ts, 90s, 180s, P traps, and valves.

“BIM brings a lot of consistency and predictability to these projects,” Stokes said. “Everything lines up. For example, because each floor of a condominium is identical, every floor drain for every shower is in the same location. After those floor holes have been drilled, you can stand on the 25th floor and drop a quarter through the drain hole, and that quarter has a good chance of going right through all 25 holes.”

BIM generates a bill of materials, and the plumbing shop can make subassemblies offsite, knowing that they’ll fit when they get to the site; the risk of wasting time on rework is negligible. This also helps to keep site inventory to a minimum. Inventory at a construction site is at risk for theft, and in many cases, the construction contract limits the tradesman to keeping no more than three days’ worth of inventory on the site at any time to prevent crowding and congestion.

Finally, it provides full transparency for the project. Everyone with a hand in the project—design engineer, contractor, and owner—has full access to order status in real time, 24/7.

Beyond BIM. Technologies keep moving forward, and equipment manufacturers incorporate them as quickly as they can. CAD replaced hand-drawn prints, CNC machines replaced machines that ran until they hit hard stops, and enterprise resource planning systems allow manufacturers and fabricators to track a dizzying array of details. The next wave of technology is upon us. It’s connectivity, and it uses technologies such as Wi-Fi and the Internet to enable the Internet of Things or, in industry parlance, Industry 4.0, and T-Drill wove this concept into the design of its latest machine.

Cut, Drill, Pull, Measure

T-Drill combined its accumulated decades of experience in equipment development, its work with Cannistraro, its understanding of lean principles, and connectivity technology to create a new machine that makes components for many industries, not just plumbing. Introduced in prototype form at FABTECH® in 2017 and prepared for display at Tube® 2018, the S-80 was designed to be versatile enough to complement most existing shop operations and advanced enough to have a place in Industry 4.0.

“The machine is a platform,” Stokes said. “You can feed the material in by a rack, conveyor, or robot, and feed it out the same way. Also, a tube cutter can feed it.”

After the workpiece is in place—it sizes up to 4 in. OD and wall thicknesses up to Schedule 10—the machine drills all the holes of a common size, rotating the workpiece as necessary. It then exchanges that tool for the next drill size and continues until it has completed all of the holes.

“It has a tool changer and a tooling library that holds up to 20 tools,” Stokes said. Tools include regular drill bits for common holes; collaring heads to make holes and pull collars for plumbing; hole saws for large diameters; flow drill tooling and tapping tools for furniture, shelving, and other applications that need a sturdy anchoring point for assembly hardware; burnishing tools to make slight adjustments to hole sizes, if necessary; and abrasive buffing and polishing tools, including buffing compounds, for applications that need an excellent surface finish, including ultrahigh-purity components.

Of course, tools wear, but the machine helps to compensate for diameters that change.

“An optional laser scanner measures hole sizes,” Stokes said. “If you pull a collar that is 0.005 in. undersized, a burnishing tool can correct that,” he said. The laser is accurate to ± 0.001 in., he said.

Connectivity means that it imports orders through the cloud, and users can use a mobile phone to monitor order status. It also does a little forecasting so users can determine when future orders will ship.

The machine’s monitoring system keeps on eye on operating parameters, such as the lubricant level and tool activity, and generates alerts when necessary so the operator knows when the lubricant is running low or a tool has broken. It monitors other parameters for maintenance purposes.

“It monitors heat buildup, belt wear, bearing wear, and the number of parts produced since the previous maintenance action,” Stokes said. Also, the machine’s software notifies the user when preventive maintenance is due.

Beyond replacing an empty rack of raw material, adding some lubricant, or performing maintenance, operators don’t have to do much to run the machine.

“Going out to the shop floor should be a thing of the past,” Stokes said.

T-Drill can be contacted at:

• T-Drill Oy, Ampujantie 32, FI-66400 Laihia, Finland, 358 6 475 3333, sales@t-drill.fi

• T-Drill Industries Inc., 1740 Corporate Drive, Norcross, GA 30093, 770-925-0520, sales@t-drill.com, https://t-drill.com

• Tube 2018: Hall 5, booth A01

About the Author

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI