Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Our Publications

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

College friends invent a 3D printer

Cincinnati Inc.’s small-area additive manufacturing system evolved from the work of four MIT students

- By Don Nelson

- November 3, 2019

- Article

- Additive Manufacturing

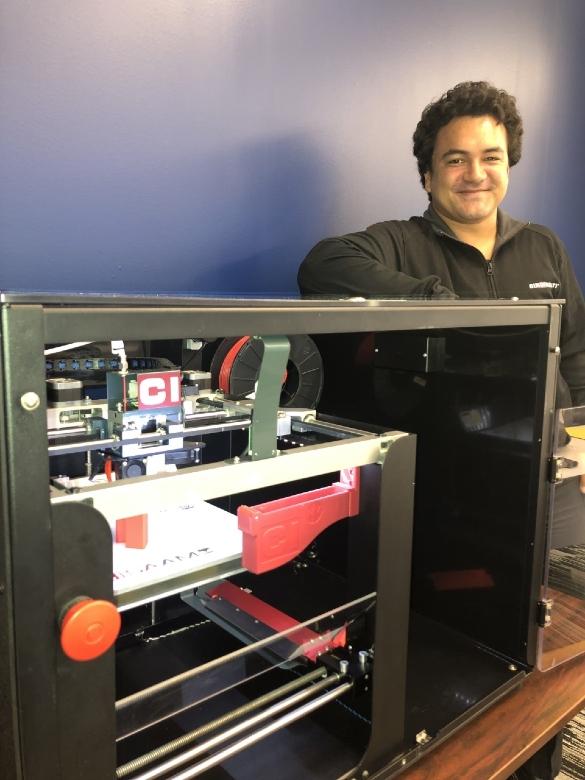

While at MIT, Chris Haid was one of several engineering students who developed what is now Cincinnati’s SAAM 3D printer. D. Nelson

If you ask most people to name an activity fraternity brothers engage in, few would answer, “Build a 3D printer.” But that’s what Chris Haid and three fellow students at MIT did in 2013.

“We were in the same fraternity, and we’d spend a lot of time together on weekends doing various 3D printing projects,” said Haid, current general manager of Cincinnati Inc.’s additive unit. “We had all these cool inventions and designs and no way to make them. So we built a 3D printer”—from 3D-printed parts. Despite having access to their own printer, however, it was still “hairy” scheduling ample time for each student to complete his projects. “A print job would take too long or [the machine] went down and the whole schedule was out of whack,” explained Haid.

A major obstacle was having to unload jobs manually. So the foursome developed a scraper mechanism that automatically removes a finished job and prepares the printer for the next job. The group searched the internet for a similar automechanism but found nothing, said Haid. MIT helped them secure a patent for the technology. (The patent, “Automated Three-Dimensional Printer Part Removal,” was awarded in March 2016.) Shortly thereafter, the four launched a company, NVBOTS, to market the system.

Cincinnati acquired the startup in November 2017. Haid joined the company, as did another of his co-inventors. The AM system built by the MIT students evolved into Cincinnati’s SAAM (small area additive manufacturing), an FFF-style 3D printer with a build envelope measuring 7.9 by 7.4 by 9.4 in. The company introduced the SAAM HT at the 2018 FABTECH® show.

Haid said the base model SAAM is well-suited to printing parts from inexpensive polymers, like PLA, and can be used to build the devices and tooling commonly found in fabrication shops. The SAAM HT, on the other hand, prints parts from much stronger materials, like PEEK and ULTEM, he said. A printer capable of handling high-temp materials is “going to be much more in line with what I think we’ll see being used in the future for producing tools.”

The differences between the base and HT models are that the latter features a high-temperature nozzle and print bed, its enclosure is actively heated, and the motor and related components are liquid-cooled. The two SAAMs join Cincinnati’s MAAM (medium area additive manufacturing) and BAAM (big area additive manufacturing) 3D printers, as well as the company’s lines of press brakes, lasers, shears, plasma cutting machines, and automation systems.

D. NelsonAbout the Author

Don Nelson

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8248

About the Publication

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI