Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A matter of asking the right questions

Fabricating good parts is now a given; managing a good process, not so much

- By Tim Heston

- July 28, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

Recently Kyle Edwards, president of Triton Mfg. Co. in Monee, Ill., gave a tour to a longtime customer that for a quarter-century had sent the company $300,000 in work annually, mainly for two parts. These provided a sizable but not massive slice of business for the $26 million precision metal fabricator.

“The representative saw our facility and said, ‘I can’t believe we’ve been buying these two part numbers from you for 25 years,’” Edwards said. “Now the customer has other divisions lining up to see what we can do for them.” At this writing Edwards had heard that Triton may be awarded several million dollars in additional business. Now that’s a significant slice.

So what stopped that customer in his tracks? How did $300,000 turn into a multimillion-dollar account? Some of it was the quality of Triton’s workmanship, but it wasn’t the whole reason. A lot of it was about the company’s processes and level of organization. Parts weren’t strewn about, and workers weren’t scrambling about trying to find them. The customer could tell that Triton had scrutinized its processes and analyzed movement to minimize queue times between work centers. Workers knew what parts needed to be completed next and where they needed to go.

Over the years I’ve met buyers from OEMs in various industries. Sometimes the title on their card catches me off-guard. It’s usually some iteration of: “Purchasing, Commodity Products.” Whether accurately or not, some buyers view metal fabricated products as commodities, and at an upper level it’s understandable. Few precision fabricators build proprietary machines, and there’s no legal reason stopping the shop down the street from buying equally capable equipment. The only barrier is cost, which requires a healthy balance sheet.

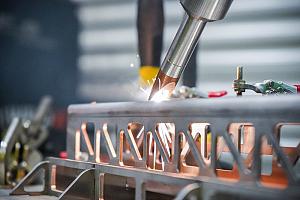

That’s where the “noncommodity” part of the equation comes into play. Every shop owner tells me that it’s the people who make the difference. But it seems that, at least in a shop with a lot of modern equipment, people contribute differently, at least when you compare their workday to those of previous generations. Hands-on processes like welding and polishing remain skilled crafts. How a technician wields a GTAW torch or polishing wheel can make the difference between winning and losing a job. The same holds true for, say, an operator who can set up, program, and quickly change over an older press brake. A skilled technician may be able to work some magic on old, tired equipment.

But in a shop with well-maintained, capable machines, technicians contribute differently. They focus on product quality, for sure, but they also focus on something else. Workers have powerful tools at their disposal: Solid-state lasers churn out parts at unprecedented rates, electric brakes and folding machines form parts in a flash, and robot welding cells join a subassembly in record time. If everyone focuses on “feeding the monster” to keep the machines running, they’ll flood the shop with work-in-process and warehoused goods that the customer doesn’t need yet.

To that end, they focus on the process, and that’s also what drew the customer to Triton, where employees don’t just ensure that machines are simply running, but also that parts are flowing and, most importantly, shipping.

“The gemba walk is probably the most consistent thing we do from a lean standpoint,” Edwards said. “A cross-functional team of managers walk the floor on a weekly basis. We review productivity numbers, their 5S score, their quality numbers, and any continuous improvement projects that we have underway in the cell.”

A recent improvement project involved bulk-packed components Triton regularly receives from a plating shop 30 miles away, which turns jobs around in about 24 hours. Previously parts were delivered in a large bin. Some components were part of higher-volume orders that have dedicated lines on the floor, while others were for small- and medium-volume jobs, each of which have a different routing. This arrangement made for a lot of wasted movement.

To improve matters, Edwards explained, employees asked questions. “Once we get it, how do we trip over it? How do we double-touch it? How do we move bins to get material? Our product mix changes, so we needed to develop a fluid methodology that can ebb and flow with the product mix.”

After a kaizen event, Triton devised a system in which large-volume parts stay near the loading dock, where they are processed with little or no movement, while the remaining parts are divided up based on routing instructions.

Considering this effort deals directly with an outsourced process, Edwards said that the next step may be to communicate with suppliers, extending improvement efforts up the supply chain. Could parts be delivered differently? What would be possible?

When you get right down to it, healthy dialogue and clear thinking seem to be at the core of continuous improvement. Say a shop has four weeks’ lead-time. What takes up all that time? Cutting, bending, and welding take a matter of hours, but queue times may take days. So everyone works to reduce that time with, again, clear communication: 5S, clear signage, clear work instructions for changeovers, easily accessible tooling, up-to-date information on the job traveler, and so on. Once parts are flowing, what’s next? Perhaps it takes two weeks to get parts back from the custom coater. How can that time be shortened? Healthy dialogue and improvement ensues again.

Some purchasers may view a fabricated metal product as a commodity, and if it’s a simple enclosure or flat piece-part, it may well be. But they’re not buying products, really. In part, they’re buying expertise, like in a shop that has star welders. But they’re also buying capacity. Incredibly productive machines have made even capacity a bit of a commodity—but not flexible capacity. Modern machines have features designed with quick changeovers in mind, but they still just do what they’re told. On their own, they can’t respond to customer demands while juggling a thousand other part numbers. Here, having the right people asking the right questions can make a world of difference.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,