President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Costing and pricing it right

How costing evolves in a growing shop

- By Ken W. Mikesell

- April 8, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

Bob Cramer felt like he was in over his head. He had recently won a new contract that could either quadruple his fab shop’s revenue—or kill it.

Due to unforeseen process limitations in his shop, the required investments in new equipment had grown to $2 million, and an increase in operating expenses came with it. The facility was large enough to handle the growth, but he still would need to make some infrastructure investments. The impact of all these new employees and operating and equipment investments weighed heavily on his mind.

A Busy Few Months

Four months previously Bob had a long conversation with Phil Monroe, a CEO of another, much larger manufacturing company, and fellow hockey dad. At that initial meeting Phil challenged Bob to step up and accept a new role as a business leader and take on this business opportunity. (Editor’s note: See “How a welder becomes a leader” from the March 2019 edition, archived at www.thefabricator.com.)

Bob didn’t embrace his new role easily. And the initial decision to take on the new project was much simpler than the reality of making it happen. He felt like he had jumped from the frying pan into the fire.

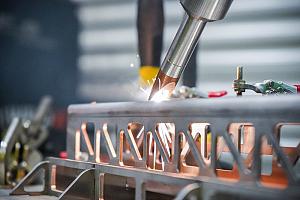

Initial orders from the new contract had already started, and the shop was struggling on many fronts. The company hired more people, but many weren’t fully contributing yet. Even worse, the product quality and finish expectations were a stretch for the process capabilities of their plasma cutting table, so they had to outsource the plate parts to a laser cutting subcontractor. The products also included various machined shafts and hubs as part of the weldments, and the fab shop’s machining supplier had trouble delivering on schedule.

Higher-than-planned outsourcing costs were affecting margins. Fortunately, initial make/buy cost assessments showed that if new equipment were purchased, then these margin losses could be recouped. Also, if the numbers worked out, the bank was open to providing equipment financing or capital lease arrangements.

Still, new equipment and processes would bring their own financial challenges, beginning with higher operating costs from the payments plus the additional operating and consumable costs. New processes would require new expertise, which would mean hiring new staff and technical leaders. All that would only add to the profit margin challenges.

Given the expected size of the workforce by year-end, Bob planned to hire more floor leaders and office staff. He had started the search for an operations manager who would take over some of his prior duties. And because of his concern over managing the finances of this more complex business, he had already hired a financial comptroller.

In light of these margin issues, Bob and the comptroller began looking at the books and the company’s existing costing practices. At its beginning, the business took an informal, back-of-the-napkin approach, and for the most part it worked OK. Overall, the company made money.

Over time the business started the practice of allocating overhead to labor hours, but often they could not fully grasp how well they did on an individual part basis. This was risky, especially because of all the costly new processes planned.

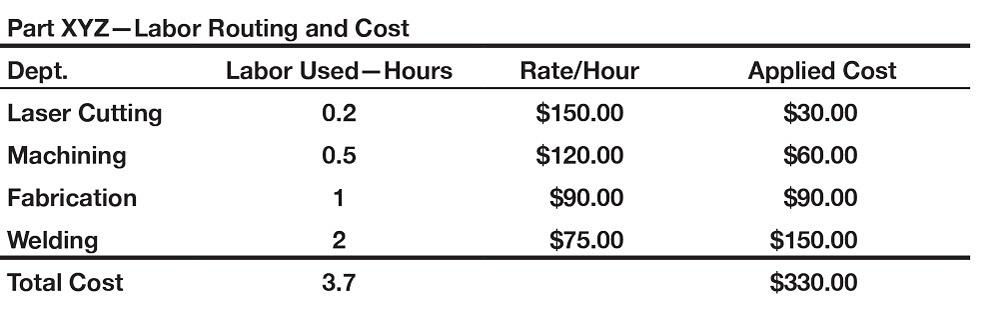

Figure 1

To find the applied cost in activity-based costing, a shop simply takes an hourly rate and multiplies it by the labor hours used. This common method isn’t so common in the smallest of job shops, but for a growing manufacturer, it’s essential.

They eventually determined they needed to create a product costing system that reflected the restructured business. Faced with new challenges, Bob sought insight from someone he trusted—and so he arranged another meeting with Phil.

Bob was headed to the meeting now and Phil was bringing someone he thought could be of help. Deep down Bob felt a bit anxious but also hopeful that he would discover the insights he so desperately needed.

Basic Costing

As Bob approached the table at the diner, he saw Phil was sitting with someone. Phil stood and introduced Steve Peterson, an operations consultant who had helped Phil with his business—and someone who could help Bob with his product costing and pricing conundrum.

After they had finished eating, Bob said, “As Phil may have already told you, in recent months we have been on a growth fast track to take on some important new business. This growth will drive the addition of new capital equipment, more shop employees, and more leadership overhead. It’s an exciting opportunity. But with our growing business, our cost structures are changing, and we need to get a handle on them. If we don’t, we could be either giving our work away or chasing the new customers away with high prices that aren’t warranted.”

Steve nodded. “You are not alone. Many businesses, surprisingly some quite large, wrestle with having accurate product costs. This is because every employee and added capital investment changes the cost structure of the business, and if the scale of the changes is large or disparate enough, those changes can greatly skew product costing. That said, tell me about your business. What equipment do you have, and what processes do they perform?”

“Well, right now most of our employees are fabricators and welders,” Bob answered. “We have a plasma table, multiple brake presses, some ironworkers and drills, and various cutoff equipment for structural materials like tubing, angle, and pipe.

“We have wire feed welding equipment plus some TIG and plasma welders for more precision jobs. And we have a collection of weld positioners, weld tables, and material handling cranes and forklifts to support the assembly and welding of our products. We have a bunch of lower-cost tools such as grinders, drills, and clamping devices. We’ve had all our equipment for years. It’s all fully paid for and depreciated.”

Steve responded, “That’s helpful. To support your growth, who are you hiring, and what new equipment are you looking at?”

“As for equipment, we’re thinking about adding a laser cutting machine along with a CNC brake, plus an entire new department with several new machining centers used to machine and key the many shafts and hubs that go into our products. As for personnel, we’d need to hire operators for these new machines plus more welders to deal with the increased volume. Of course, each of these stations will need the associated support tools and equipment, as well as technical staff to support their processes.

“We now have 15 people in the shop and five overhead personnel. All this expansion probably will increase those numbers to nearly 60 shop folks and maybe 10 leadership and office staff. Of the five additional office support personnel we already have added a financial comptroller, and by the end of the year we’ll add an AR/AP clerk, a buyer/planner, a manufacturing manager—who ultimately will be my shop floor replacement—and an engineering technician who will deal with machine programming as well as jig and fixture design and build.”

Steve piped in, “That’s a significant change in capital and employee costs. So how do you currently perform product costing?”

Bob responded, “We currently define the costs by breaking out materials, labor, and overhead. Once we have this total, then we add the margin for the job’s selling price.”Phil looked at Steve and then jumped into the conversation. “What exactly goes into materials, labor, and overhead?”

“The materials are straightforward,” Bob said. “We include the net material used in the product plus some portion of drop that ends up in recycling. For sheet metal and plate, we have material yields between 75 and 90 percent, depending on the part shape, and around 80 to 92 percent for structural material, depending on the lengths and drop. Periodically we balance out the billed material and waste against inventory to ensure our yield estimates are accurate. We feel pretty good about this number. And we should be able to get even better yields with new equipment and nesting software, along with planned improvements in scrap reporting practices.”

“OK, you seem to have a good handle on material costs,” Steve said. “How do you define labor costs?”

“For direct labor we consider wages and the directly associated costs such as FICA and the like. The workers’ comp and health insurance costs are charged into overhead.”

Steve nodded. “That sounds like a good breakdown of labor. Speaking of overhead, what do you include in that category?”

“Well, we include everything else—the indirect labor and other employee and process costs. All shop supplies, utilities, insurance, building costs, plus all other payroll costs go into overhead. And once we add all three prime costs—materials, labor, and overhead—we then add the margin to get our price.”

“Overall, that still makes sense,” Steve said. “How do you allocate the overhead to each product?”

Bob responded, “We take our total overhead costs and allocate them over our total direct shop hours, then apply this as an hourly rate based on the amount of direct labor applied to that part.”

Steve continued to nod. “That’s actually a pretty good start. In fact, it’s a much better process than many businesses use. However, with the personnel and equipment changes you’re planning, this method will start to cloud the true costs for a given product. It could even drive you to make poor decisions in the future.”

Bob nodded. “That’s what we’re afraid of.”

Activity-based Costing

“I’d recommend that you begin by splitting up overhead into two components: fixed and variable overhead,” Steve explained. “The variable portion will contain most of the same elements you already have in that category, but fixed overhead will split out the costs that don’t change each month.

"In other words, the fixed costs would be those unaffected by whether your doors are open or closed. This could be building rent, insurance, legal bills, salaries for the nonproduction office people, and the like. To give you a sense of scale, this number could be between 8 and 12 percent of total revenue, while the variable portion is often multiples of this number.”

Bob responded, “That makes sense, and I think these fixed costs would be easy to break out. What about the variable costs? Is it just the balance?”

"Well, yes and no,” Steve continued. “It is the balance of the overhead costs, but let’s go deeper into assigning variable costs. While it is the balance of the total, how it’s allocated is where the problems arise.

“You stated before that you spread the overhead costs over the production hours for an applied rate. In a business where costs are somewhat equivalent across most work centers, this can be fairly accurate. Your current business is probably in this situation, since you have older, fully depreciated equipment. Other than differences in consumable costs for your various processes, your individual variable costs may be within 10 to 15 percent of each other. So as long as you allocate labor hours accurately to each product, you could apply the same overhead rate across any hours expended in the plant, and still be pretty close.“Your growth plans will change this, though. The new capital expenditures will add large monthly payments, incremental consumable costs, and new indirect support costs to the laser and machining centers. These new overhead costs will be significant, and you’ll be applying them to relatively few direct labor hours.

“For comparison, a welding process might have overhead costs for labor, consumables, supplies, and equipment of $25 to $35 an hour. But the new laser cutting and machining equipment overhead rates per output hour could be three to four times that amount, and you’ll need to apply this to each associated labor hour, which is a significant difference.

“And here is where the danger is. Many companies just blindly add all the new equipment and operating costs into the one overhead account and then spread this over the total hours applied in the shop. What do you think happens when shops do that?”

Bob quickly responded, “I would guess that the cost per hour in the welding shop would become substantially overstated, while the costs of the hours on the laser and machining centers would be substantially understated.”

“You’re right. And what kind of decisions do you think that business will make based on this costing approach?”

“Well, based on inaccurately applied overhead costs, I could see them unnecessarily overpricing their welding and fab processes, which would drive business out of the shop in these departments. On the flip side, products going across the new equipment could be dramatically undercosted. Although they might have lots of business booked across those new machines, because they were not covering their true costs in their pricing, the business would never get a true return on their investment.”

Steve nodded in agreement. “But there is a way to deal with this. It’s called activity-based costing. Instead of having just one cost center across the entire business, you’d now include many more cost centers tied to each unique process.

"For your business, I could see you grouping each of your fabrication and welding departments into two separate work centers, each with its own costs. This might mean you would have a fully burdened rate—labor plus variable and fixed overhead—of say $65 for welding and $75 for the fabrication and plasma cutting department, just for discussion. The laser cutting and machining center departments might then need to be roughly $150 and $120 per hour, respectively, to cover their unique costs of operation.

“You’d apply these varied costs to a part simply by allocating the amount of time used in each department to a given part or assembly. So if it took, say, 0.2 hour to cut a part on a laser, you’d multiply 0.2 by the burden rate of $150, and get $30. You’d then do this for your other work centers. Here, let me show you.”

Steve took a napkin and wrote out the costing of a simple part routed through laser cutting, machining, fabrication, and welding (see Figure 1).

Bob sat quietly for a moment. “Well, that was simple. So what do I need to do to get this started?”

Phil quickly stepped in. “I can field this question. Steve helped us get started when we did this at our business. It was a bit tedious but much easier once you got going. Speaking simply, we first determined which departments should be broken out into separate cost centers based on the cost differences.

“Then we determined which costs should be fully allocated in a department or shared between departments each time period. We next determined the hours each department would work that time period. Finally, we took the total costs and divided by the total hours in that period to get our cost per hour for each department.

“Some of the details on the labor base used, such as indirect labor and efficiency, took some extra time to develop in each department, but once we understood, then the mechanics of the process were straightforward.

“We then identified how the hours were used on each part in each department, just as Steve did with the table he created. It can either be a manual route sheet for each product or you can do it in an ERP system. Then we created our cost data by adding materials and desired margins to determine our selling prices. It was detailed work, but we now have a lot more information on our production costs and can therefore price out new business with confidence.

"And not using our prior one-overhead burden approach came with additional benefits. When the business is running at near full capacity, we are basically already covering all our fixed costs. Therefore, in those instances we can consider using a contribution margin approach for costing additional new business, which leaves the fixed costs out of the equation. This means we can add the margin to the sum of material, labor, and variable overhead, selling it at a discount equal to our fixed overhead, and still make the full margin on this incremental business. On multiple occasions this approach allowed us to take on projects using overtime to drive higher profits than we thought possible.”

Driving home from the meeting, Bob kept shaking his head and smiling. It had been a great, productive meeting, much better than he had expected. Before they parted, Steve said he’d call to arrange for a visit. Bob’s mind was off and running. He had just paid for three breakfast plates, but he came away with so much more.

Ken W. Mikesell is president of Lean Enterprise Solutions LLC, Arvada, Colo., 720-318-9191, www.bottomlinefix.com, a business and operational consulting and executive coaching firm. Mikesell brings almost three decades of metal fabrication, welding, and machining experience to his practice. A certified welder himself, he still spends his spare time creating unique metal products for a variety of markets.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,