President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Job shop management: Are scheduling problems really symptoms?

A shop organization chart gets to the heart of scheduling problems at a fabrication facility

- By Vincent Bozzone

- January 29, 2020

- Article

- Shop Management

Scheduling at a metal fabrication shop can be a mess. The root causes, though, might not have anything to do with scheduling. It comes down to the overall job shop organization. Getty Images

When scheduling is out of control, chaos reigns as the production schedule is in a constant state of flux. This is not uncommon. Scheduling is one of the most difficult aspects of managing a job shop. Complaints are many, solutions few.

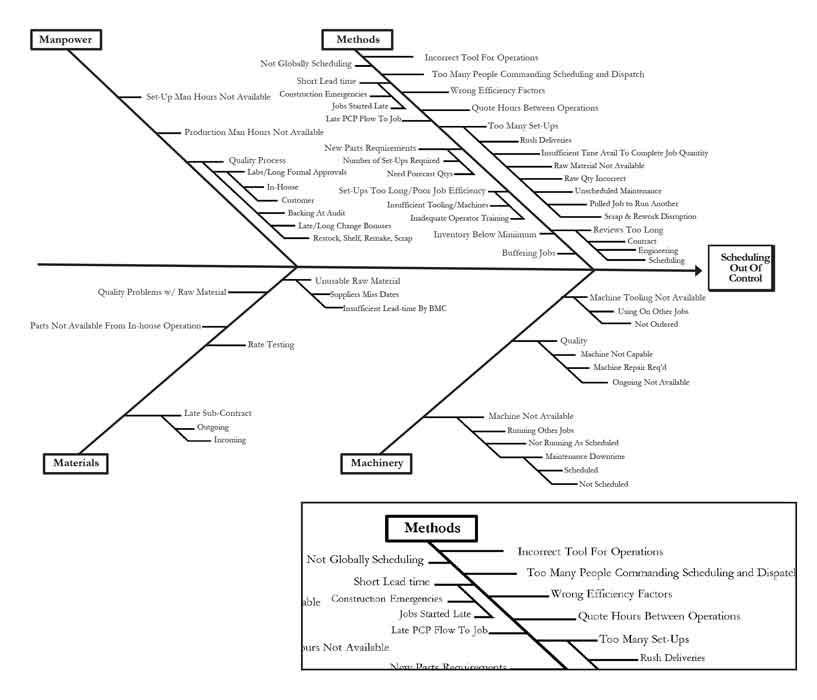

Consider a Kentucky job shop that needed to get scheduling under control. Using an Ishikawa fishbone problem-solving method (see Figure 1), managers identified more than 60 separate conditions that disrupted the shop schedule—from late delivery of materials to incomplete specifications to employee absenteeism—and set about trying to resolve them. After a year of concentrated work, guess what? Scheduling was still out of control.

The Ishikawa fishbone is built on five M’s that make up the five branches of the diagram: materials, manpower, machines, methods, and measurement. The Kentucky job shop’s fishbone had one M missing, though: measurement. The reality was that shop personnel had no measurement that would let them know whether scheduling was under control or not. At the end, they simply wrote, “Scheduling is out of control.” A stated problem is not a metric.

When you take a closer look at this multitude of schedule disruptions, it looks a little fishy. There are just too many things that can go wrong. In fact, you can trace each reason back to every department in the organization. This suggests that scheduling is an organization-wide problem, not localized in scheduling.

If you are going to solve scheduling problems, you must get beyond the bounds of scheduling and take the organization as a whole into account. If you have been trying to control scheduling and are not having much success, then maybe it’s time to take another look and try something else.

Communication Chaos

Poor communication and feedback rank among the top problems reported by employees, according to the Center for Management & Organization Effectiveness. This is a matter of statistics rather than a human failing. The permutations and combinations of communication links in even a small organization can reach into the hundreds.

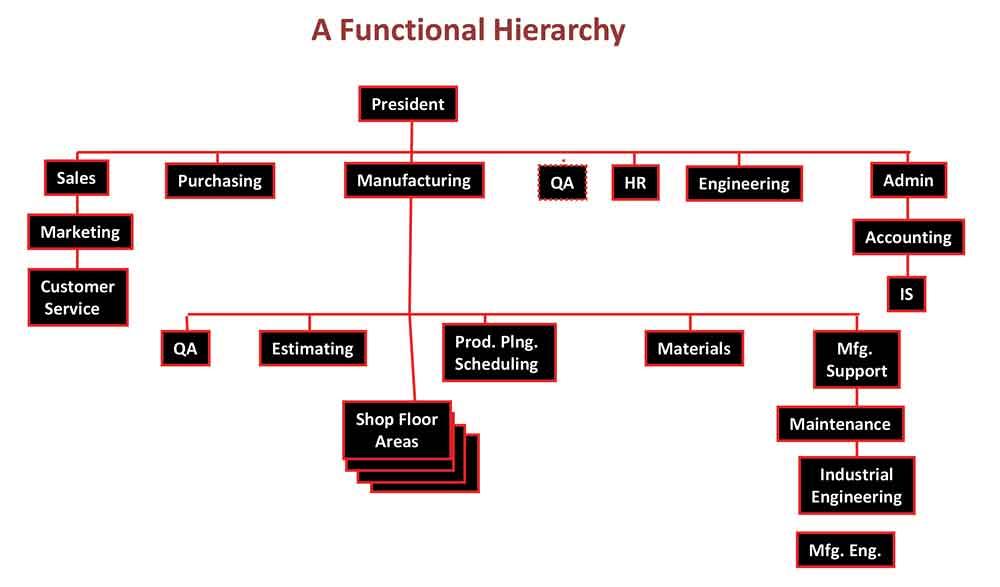

These communication links reflect the traditional pyramid organization model that is broken down by departments and subdepartments according to functions and skills (see Figure 2). The number of connections makes communication difficult, especially on an organization-wide basis.

All this makes it virtually impossible to coordinate everything that can disrupt the production schedule. The pyramid model, with its departments and divisions, has been the norm in manufacturing organizations since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Maybe it’s time to re-examine it.

Job Shops Are Unique

The pyramid organization works well for mass production because volume is high and anything that goes wrong can add up to waste very quickly. The pyramid organization with its specialties and subspecialties provides the detailed focus required to monitor and control all aspects of production. But this is not the job shop environment.

One of the many differences between job shops and mass production is the rate of production. A mass production business can produce the revenue in a week that would take a job shop a year to produce.

Figure 1

This fishbone diagram pinpoints more than 60 causes of a problem in scheduling. Problems are diverse, and they might point to a larger, overarching problem: the org chart.

For example, a tuna processing plant can process 20 tons of raw fish per eight-hour shift. There are 32,000 ounces in a ton and 640,000 ounces in 20 tons. A large can of tuna is 12 ounces, so there are approximately 53,000 cans in 20 tons. At $4 a can retail, that would be $212,000 per shift or $4,452,000 per 24/7 week. This is approximately double the average annual revenue of a midsize job shop.

This rapid rate means that production must be monitored closely. If something goes wrong, a lot of waste can be created in very little time. Therefore, organizing by departments with functions and subfunctions enables the various aspects of production to be monitored closely and controlled accordingly.

Considering this, a job shop that’s trying to get its scheduling under control might not have a scheduling problem at all. It has an org-chart problem. If a job shop assumes it should copy a mass production pyramid model, it is making a big mistake.

For years job shops have attempted to adopt concepts and tools from mass production manufacturing—and they’ve usually failed. For example, the idea that a schedule should control the shop floor might be appropriate in a more stable mass production environment, but it is woefully out of place in a job shop. Statistical process control is another example; the volume in a job shop is insufficient to support the use of this tool.

Job shops need an organization model that is different from the pyramid model of large industrial organizations. This is not an obvious problem, because the job shop org chart is taken for granted and so becomes invisible. It’s difficult to connect the dots between scheduling problems and the need for a new organization model. Nevertheless, this is the real reason for an inability to schedule jobs and deliver on time.

A Lack of Alignment

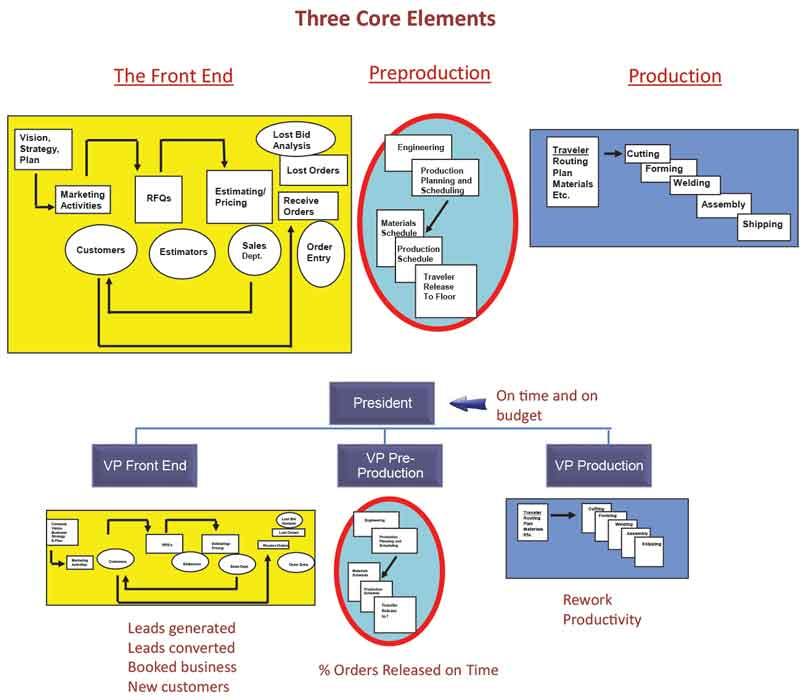

Order-driven job shops that produce to customers’ specifications operate on an entirely different system than a make-to-stock mass production system. All job shops follow a common process for generating business and converting a customer’s order into a finished product (see Figure 3).

When you superimpose the industrial pyramid organization onto this business cycle, you’ll find that the two don’t align. This lack of alignment makes it impossible to manage the job shop business processes.

What does this have to do with scheduling? When you recognize that scheduling problems originate from within the organization as a whole, you can see that a localized solution in the scheduling department is not going to solve the problem. You might need a different model for managing the shop, one that allows you to manage the business process directly, not through the filter of the industrial pyramid. When you can’t manage the business processes, it’s easy to see how an out-of-control process can also create scheduling problems.

Why the Pyramid Fails in Job Shops

Using the pyramid model does not allow you to manage the business process directly, but only in piecemeal fashion. You’re presented with problems in terms of departments and specializations. You have “sales problems,” “quality problems,” “scheduling problems,” and so on. These categories will drive you to seek solutions within the bounds of the department, and it can blind you to the need for systems thinking and an organization-wide solution.

This is the case with scheduling, where problems arise from disconnects in the organization as a whole. You don’t need to find new ways to manage all the disruptions; instead you need to reduce the number of disruptions in the first place. You can do this by getting the business process under control so that everything operates more predictably.

Figure 2

The functional hierarchy, or industrial pyramid, has origins in mass production, not the job shop.

This requires a new way of looking at the job shop, organizing it, and managing the business process directly as it converts customer needs into orders and finished products. The pyramid is the problem; a new paradigm in job shop organization is the solution. Job shops have to abandon the industrial pyramid model for one that more closely fits how a job shop actually works.

Look again at the common steps job shops follow for generating business and converting a customer’s need into a finished product. This is the heart of every job shop business, and it requires an org chart that aligns with it.

So what does this new job shop org chart look like? What makes it different from a flavor-of-the-month fad? How does it work? How hard is it to adopt and put into practice? What kind of results can you expect? Read on.

The Role of Preproduction

Look again at the fishbone diagram and all those causes. Too many setups. Short lead time. Quality problems. Setup hours not available. Wrong efficiency factors. Unscheduled maintenance. Pulled job to run another job.

You’ll see that many causes on those branches connect in some way to a lack of coordinated production planning. This has to do with a critical element in the job shop business cycle: preproduction. Quite often, once a sale is confirmed, the front office simply throws the job “over the wall” to production. There’s no formal preproduction process. As we all know, the devil’s in the details, and a good preproduction process should uncover them. This can be anything from setup difficulties at the press brake to material requirements.

If they’re lucky, setup personnel or supervisors might be able to develop setups and manage other details between repeat orders or other previously run jobs. They’re essentially squeezing preproduction into production, and they do what they can. But many jobs reach the floor half-baked. Press brake tooling might not be available at the right time. Material might not be available. A machine might be down for preventive maintenance.

Yes, not every problem comes from a lack of preproduction planning. Someone might not show up to work, for instance. Even so, one missing person shouldn’t throw a wrench into the entire production schedule. If it does, you’re probably managing a chaotic environment, one that can be made much less chaotic with good planning.

The Right Structure and Incentives

Simply creating a preproduction department or process doesn’t get to the heart of the problem: the inappropriate org chart. The pyramid structure incentivizes people to concentrate “locally” on the task in front of them. The more CAD drawings a technician can clean up in a certain period, the better his job performance. He’s not looking downstream, where he’d see that the print he unfolded in 3D CAD really can’t be bent on any of the company’s press brakes effectively, mainly because of sequencing and workpiece- and tool-collision problems. He sure works quickly, though, even though he’s sending problems that snowball into utter chaos in the shop. But thanks to the industrial pyramid, he basically works with blinders on.

A job shop org chart ideally should align with the job shop business processes, which can be grouped into three distinct areas (see Figure 4): the front end, preproduction, and production.

The front end includes marketing, sales, estimating, and customer service. The preproduction department includes engineering (which could include physical tryouts of difficult parts), production planning and scheduling, materials and production scheduling, quality protocols establishment, routing, and traveler release, at which point the baton is handed off to the production department. However, when preproduction is incomplete, production has to make up for it on the floor.

Each area focuses on making that baton pass as easily as possible. This puts communication front and center. Estimators in the front-end department might make their way through a mountain of request for quotes, but if these orders get stuck in preproduction because of unanswered questions, the front end dropped the baton, and their performance suffers. The same incentives go for the baton-pass between preproduction and production.

What about support functions like QA, manufacturing support, and maintenance? The exact organization depends on a job shop’s niche and product mix; but wherever these support functions are placed, they should support, and not work against, the job shop business process. For instance, a job shop might decide to put maintenance in preproduction so they can work closely with planning and scheduling. In this way, planned maintenance should never stand in the way of on-time delivery.

About Reliability

A customer bases its decision to award work to a job shop typically on some combination of price, lead time, and quality. But another factor might be more important than the others, and that is reliability (see Figure 5).

A customer wants to be confident that a job shop will deliver the order on the promised date. This is especially true when customers have their own timelines for completing a larger project. A low price from an unreliable vendor can be easily wiped out when orders are not received on time. Job shops undermine their competitive position when a customer can’t count on them to deliver on a promised date. Time-critical work could go to a more reliable vendor; the unreliable shop might never even see the RFQ. How can a shop achieve such reliability? Again, it starts by looking at the big picture and aligning the organization with the job shop business process.

With a solid preproduction process complete, the production department should be able to handle a variety of products with few surprises. Operators have material staged along with clear setup and inspection instructions. The production department no longer deals with chaos, but instead an orderly flow of diverse work. If someone doesn’t show up or a machine breaks down unexpectedly (and in the real world, these things will happen), the production department can deal with the problem in an orderly fashion, reschedule the work, and keep the flow going.

This solves the scheduling problem, and on-time-delivery performance skyrockets—not by scrutinizing the scheduling process itself, but by seeing the big picture and tackling the root cause: a misalignment between the org chart and the job shop business process.

Vincent Bozzone is president of Delta Dynamics Inc., 248-961-1380, vincent.bozzone@gmail.com, jobshop360.com

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

Young fabricators ready to step forward at family shop

Material handling automation moves forward at MODEX

A deep dive into a bleeding-edge automation strategy in metal fabrication

White House considers China tariff increases on materials

BZI opens Iron Depot store in Utah

- Industry Events

Laser Welding Certificate Course

- May 7 - August 6, 2024

- Farmington Hills, IL

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,