CEO/Co-founder

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Moving shop in metal fabrication

OSH Cut CEO reveals lessons learned and its company's readiness to scale during big move

- By Caleb Chamberlain

- April 10, 2024

As I write, OSH Cut is finishing up a move to a new, larger facility. We opened in 2018 with a little under 6,000 sq. ft. of shop space and no office. We outgrew that tiny space almost immediately. In the following five years, we took over the leases on two adjacent units, expanding to around 20,000 sq. ft. and still bursting at the seams.

Late last year, as part of our expansion into tube cutting, we opened a new 52,000-sq.-ft. facility. We started moving equipment in January, and as of early March, all our equipment was in our new space and online. It was a big job, and not everything went according to plan. But we learned a lot, and in the process we developed new software automation to help us stay ahead in the future.

Best-Laid Plans …

We planned out a move that would keep production flowing uninterrupted even as we shut down and moved equipment. We’d start by setting up a line at the new facility, and then gradually send it work as it came online. This transition would be facilitated by software, which would automatically assign incoming work to one of the two shops based on capability, capacity, and inventory availability.

The inventory piece would be a big win: Moving all our inventory would be a challenge, but we keep only three to five weeks of raw material in stock at any given time. We could “drain” the old shop of inventory by fulfilling orders there whenever we could and then order all new inventory to the new site. With our scheduling software assigning work based on inventory availability, volume would naturally shift toward our new shop. If all went as planned, we’d have less inventory to move, and volume would ramp up naturally, giving our new shop time to get on its feet. We’d also avoid sinking cash into excess inventory across two sites.

Meanwhile, we’d decommission and move our existing equipment (lasers, brakes, deburring machines) as needed to support the transition. When half our production was in the new facility, we’d decommission a laser and move it, a process we estimated would take two weeks. During that time, the two shops—each with one operational flatbed—would meet our production needs. Other downstream and ancillary equipment would be moved as needed to support laser volume at each shop.

To support the move, our software team went into high gear. We never designed our original software platform with a multifacility operation in mind, so we overhauled our inventory, purchasing, production management, and shipping systems so that they could function across multiple facilities. The new system allocated work intelligently, automated purchasing at each facility based on assigned work, and allowed transfers of inventory and work-in-process (WIP). This was a huge overhaul. Ironically, we’d only take advantage of the new multifacility automation for a handful of weeks during the move. It was a lot of work for very short-term use, but we expect to have multiple permanent facilities across the U.S. in the coming years.

… Of Mice and Men

So that was the plan. Nobody was surprised when the real world made the project more difficult. For starters, we really wanted to finish the move before March, since that has historically been a peak demand month. And we couldn’t move equipment on a whim. We had to engage technicians to decommission and prep the lasers, riggers to move them, and then technicians to reinstall and troubleshoot them if needed. Those kinds of plans need to be made months in advance.

Working backward from a March completion date, we needed to get everything scheduled. This meant we couldn’t be laissez-faire about moving production to the new site. A hard move deadline would make it difficult to shift production as inventory was consumed.

Splitting inventory across facilities was also impractical: It’s common for our customers to order 10 or more unique materials (type, thickness) in a single order. Assigning work based on inventory availability would mean splitting orders across facilities, requiring either manual transfers or shipping partial orders from each site. We decided to keep orders together to eliminate logistical complexity. The result was that we spent more on raw materials purchases than we hoped during the move.

Adding to the complexity, we received record-setting incoming volume in January leading up to the move. Simultaneously, one of our flatbed lasers went down and required replacement parts unavailable for weeks. Combine record demand with a 50% decrease in laser capacity, and we started the move already behind. At about the same time, key personnel required extended time off for health reasons, leaving gaps in critical areas like receiving and production.

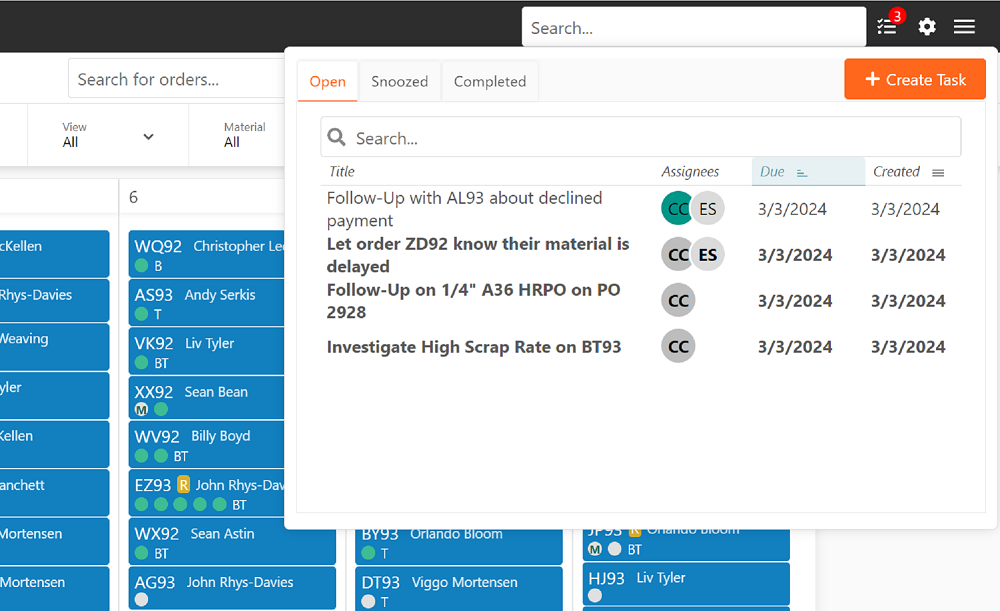

OSH Cut’s new task management system automatically detects abnormalities and assigns tasks to investigate and resolve them.

Things unraveled from there. We had piles of unreceived inventory on the floor. We had material in the wrong shop when vendors’ drivers didn’t get the memo about the address change. Material and WIP transfers didn’t always get recorded in the system right away, making it hard to know where anything was. Our people spent more time hunting for material and parts than doing value-added work, and we fell even further behind.

Stress Tests

We’ve always been proud of how well we communicate with our customers. Ordinarily, most of the critical communication is automated. Customers receive emails when they place their orders, when they are billed, and when their orders ship. Orders tend to flow through production without problems. Purchasing automation helps us get material on-site at the right time, and scheduling software ensures that we release jobs to production at the right time to finish on schedule. Meanwhile, operators’ work is automatically prioritized on our production consoles at each site, and our system keeps track of orders as they’re being produced.

That system ordinarily works well, but things started breaking in the chaos of the move. Our manual exception-handling workflow was great when three or four orders had problems at any given time. But at our worst, we finished a day in late January with 130 orders late.

We keep track of orders on an “order calendar,” which at a glance shows when orders are due and the production status of each unique material on the order. If an order is late, it shows up red on the calendar. If an order is missing material or isn’t fully released, our team can tell at a glance. Any order that isn’t on track stands out, and our team can click into each order, leave notes, and ensure that the wheels keep turning. That process worked great when there were only a handful of orders with issues. It became unmanageable when there were over a hundred. The only way to determine whether a late order needed more attention was to click through the entire list over and over again. Orders invariably slipped through the cracks, and customers didn’t get updates.

Then the reviews started coming in. Our system automatically sends emails to customers, inviting them to leave a Net Promoter Score (NPS) review and let us know how we could improve. Our customers are ordinarily ecstatic. They love our rapid, consistent service and our painless ordering systems. Our NPS is usually in the 80s (on a scale of negative 100 to positive 100, a score of 80 is extremely high). At our worst, our NPS plummeted into the 40s, and customers used phrases like “shipped late” and “bad at communicating” to describe our service. That was painful to hear. We needed to do better.

Better Software to Handle Production Exceptions

To help solve this problem, our software team heroically designed, developed, and released an automated task management system in less than one week. The new tool allows our people to create tasks, add their co-workers and have conversations, “snooze” tasks or mark them as complete, and link tasks to sales orders and purchase orders. It’s a to-do list on steroids, tightly coupled to our production management system.

The big win is that automation can create tasks whenever it sees something slipping through the cracks. For example, if an order is waiting on material that should have been delivered the day before, it will automatically create a task, reference the order and the PO, and assign the right people to it. Similar tasks can be created to handle orders that are stalled in the pipeline or that have high scrap rates, orders requiring customer follow-up, payment issues, and so on. Our system can raise its hand if it sees anything abnormal, and then our people can look into it.

We obviously have to ensure that tasks are actionable and relevant. The new system won’t help if our people learn to ignore tasks because they are irrelevant. To that end, we are working with our teams to develop task automations that help them do their jobs without becoming onerous. Our people get to design the kinds of tasks they receive and when they receive them. Perhaps someday we’ll build a user interface so that they can program task automations visually.

After a month of recovery, we are 95% moved and fully caught up. We hope that we never fall so far behind again. If we do, we’ll have better systems in place to make sure nothing slips through the cracks. And in the meantime, the task system will help us detect and resolve problems as early as possible, helping us communicate with customers more promptly and reduce late shipments.

Onward and Upward

In retrospect, a lot of little things would have helped us keep the wheels turning. Having more people trained in receiving would have helped with material delays. Setting aside specific areas for transfers, raw materials, and WIP would have helped our people locate missing inventory. We could have shut down advertising earlier to reduce workload during the move. And we could have improved communication with existing customers to apprise them of possible delays before they ordered.

Relaxing our “move by March” goal would have helped as well. Our initial plan was to take our time, easing into the new facility over six to 12 months. Instead, we decided to “rip off the Band-Aid” and perform the entire move in a month. Now that we are moved and caught up, I’m not sure I would do anything differently. It was rough, but we are finished with the move and ready to scale. The last week of February, we set a record for incoming orders and revenue. If we were still stuck mid-move, it might be even more challenging to deal with the demand than it was to push the move to completion on schedule.

This was a good exercise. It was a real-world stress test, and it exposed lots of areas for improvement. Coming out the other end, we have better software, twice the square footage, much better layout, 50% more laser capacity, and record-setting order volume. We are eager to get cranking.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

Caleb Chamberlain

165 N. 1330 W #C4

Orem, UT 84057

801-850-7584

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Fabricating favorite childhood memories

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI