- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Fabricator’s powder coating line relies on consistency and flexibility

Stable, consistent process uses versatile handling system to maximize efficiency

- By Eric Lundin and Kate Bachman

- November 3, 2019

- Article

- Finishing

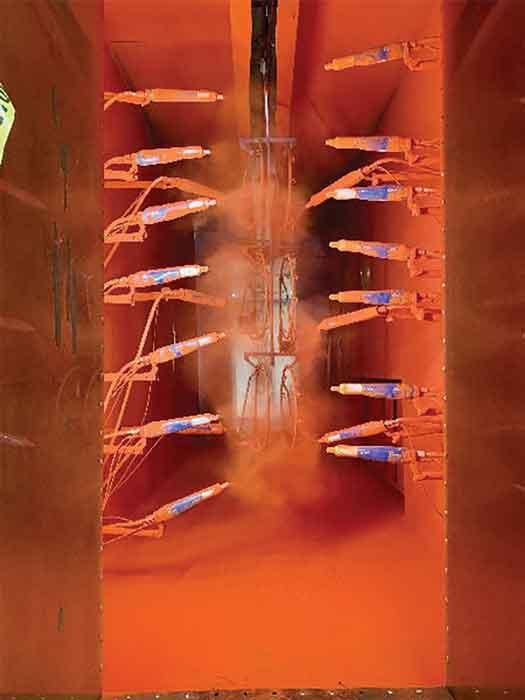

Powder coating parts for kitting saves a lot of time in packaging parts for shipment, but it creates an unending series of challenges in getting every part fully coated. Photos courtesy of Lifetime Products

You probably would never expect to see a sport fisherman cleaning a swordfish on a folding table, a basketball stand used as an engine hoist, or a grizzly bear give up on ripping open a food cooler if it had a few fishy morsels in it. And, if you visited a medium-sized fabricating operation, you probably would not expect to see an output of 100,000 items per day. That’s not 100,000 per week, 100,000 per month, or 100,000 per blue moon. That’s an astounding 100,000 items per day, and that’s the output of components at Lifetime Products, Clearfield, Utah.

A manufacturer of many recreational and outdoor items, its initial product was the first adjustable-height basketball hoop. The company went on to develop other basketball hoop innovations, such as the first breakaway rim, backboard, and three-piece stand packaged in a single carton, simplifying the purchase for consumers. Now a prolific designer and manufacturer of folding chairs, picnic and utility tables, tool sheds, swing sets and playsets, and of course basketball hoops, its products are so pervasive that they’re hard to miss. Attend a few cookouts, graduation parties, and other summer gatherings hosted by friends and neighbors, and you might well have sat on a Lifetime chair and eaten a meal served on a Lifetime table. Shoot a few baskets and you might have used a Lifetime hoop.

A vertically integrated company, it procures steel straight from the mill, fashions the material into tube and roll formed profiles, fabricates components, powder-coats them, and kits them for shipment in a process that runs like clockwork. The key to producing 100,000 parts per day? A relentless focus on process control, eliminating inefficiencies, and precise coordination so the many moving parts engage as they were intended to and everything runs smoothly.

Shooting Hoops, Shooting for the Stars

Like many manufacturers, Lifetime originated in a garage. In 1972 founder Barry Mower built the proverbial better mousetrap in the form of a sturdy, durable basketball hoop stand with a height adjustment, which he named Quick Adjust®. Changing the height is a matter of using a broomstick to give the rim bracket an upward shove. Presto! Youngsters can get into the game with an easier-to-reach rim. When it is the bigger kids’ turn to play, changing it back to the original height is just as easy.

Figuring that he was onto something good, something better than anything available in any sporting goods stores, Mower took out classified ads in the local newspaper and sold his basketball hoop assemblies to customers in the surrounding area. One thing led to another.

Founded on the strengths of a single, innovative product, the company went on to develop many more. As the product lines expanded and the company grew, the daily part volume also grew. Exponentially.

These days, the company categorizes its products into three separate systems, manufactured mainly in three buildings.

A Full-court Press

“Each building houses what we call a family of product,” said Ryan Miller, powder coating manager for Lifetime. “A basketball set is made in one building, tables and chairs are made in another building, and in our third building we run playground and shed parts.”

They’re not just legs for a common folding table. They’re part of a system that can stand up to quite a bit of misuse and a little bit of abuse.

Even though the part volume is divided up among three buildings and three powder coating systems, this doesn’t mean that its work is easy. The daily part volume still averages more than 33,000 parts per line per day. It goes without saying that line speed is a key element in its productivity.

“The volume of parts we have going through—that would be our biggest challenge for sure,” Miller said. “All of our lines run at 14 to 18 feet a minute. Trying to keep up with the output is difficult.”

Solving problems is the key, in some cases before they even crop up. Powder-coating 100,000 parts a day isn’t like solving a 100,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, but that said, doing it well is a complicated task that requires coordinating everything—the raw materials, the consumables, and the processes. To use the puzzle analogy, all the pieces have to fit together well to provide a good outcome at the end of the day.

Combining Compatibilities. First, the company puts substantial time into researching the consumables, tooling, and processes upstream of the preparation, powder coating, and curing processes to ensure compatibility throughout the system. For example, when cutting tube on a laser, the company uses nitrogen as the assist gas to prevent carbon buildup on the tube. Second, the setup personnel keep all the hard tooling segregated. They bend carbon steel on designated tooling and never use that tooling to bend stainless steel, which prevents cross-contamination. It’s a bigger tooling investment and requires more organization to keep the tooling separated, but these efforts are worthwhile, preventing carbon steel debris from finding its way onto stainless steel products. Third, for all the forming processes it performs, the company relies on a single lubricant.

It also evaluates every new powder to ensure each one is compatible with its corrosion prevention goals. Test samples undergo 15 different tests, including a 500-hour salt spray test.

Station to Station. In its powder-coating operation, Lifetime doesn’t rack common parts together. It racks parts for assembly and kitting at the end of the line, so the part organization needed at the destination starts at the origin.

“In designing the production order, we usually start with the packaging design and work backwards,” said Brad McAllister, manufacturing engineer. “We look at how those parts are going to be placed in the package. We design unique racking so that when the parts come down the line, our assemblers can take a whole unit off of one rack in an orderly fashion, assemble them quickly, and box them, ready to ship.”

Seeing the Blind Spots. The engineering staff struggles with the same challenges that all powder coaters deal with. The goal is simple—to apply the powder coating across the entire surface of every product evenly—but achieving this goal is difficult because of the mixture of parts on each rack.

The company shoots for a consistent coating thickness centered at 31/4 mils.

“That middle range of 21/2 to 4 is very good. It’s where we can hit that requirement for the range of the product and still not be wastefully throwing powder out the door,” said Mike Seegmiller, powder coating technician.

The parts are tubular, stamped, roll formed, and laser-cut. Each part, despite having unique shapes and contours, must be sprayed at the same time.

“It’s a challenge because parts that are harder to spray are racked with parts that are easier to spray. We have to position them so that they go through our system without defects,” McAllister said. “We’ve had to creatively design racking, gun settings, and iron phosphate pretreatments so that we can penetrate difficult-to-reach areas.”

“It’s important to get powder down into those blind spots so that there is adequate powder coverage,” said Seegmiller. “A too-light coating could propagate or promote rust in those areas. We have to make sure everything is covered to have appropriate mils on it.”

This means dedicating some time to working with various hanging arrangements—changing hanger design, experimenting with hanging the parts at different angles, and reducing part density—to help clear the way for more straight shots from the powder coating nozzles to difficult-to-reach areas. Beyond this, the team incorporates manual powder coating at subsequent stations. Density of the racking determines the throughput, so obviously they are positioned as densely as possible without overwhelming the manual powder coaters and assemblers.

“It’s all about being able to put as many parts as we can on a rack as efficiently as possible, yet not overwhelm the powder coating booth’s ability to coat them and the employees’ ability to keep up with that,” said Keith Maw, manufacturing engineer. “It’s a balancing act; when we spread those racks further apart, we reduce the capacity of that line and it slows production down. We do a prototype of those racks and we put the parts on them. We do a mil check on them to make sure they’re getting the proper powder coverage on them. We also see how the employees can handle the spacing.”

In some cases, it uses a completely different tack. For example, the company occasionally redesigns a part or series of parts, opening up the design for better, more thorough coverage.

Quick Color Changes. Most of the parts are powder-coated in blocks of 500 to 1,000 units on a line. After those are coated, there is a small gap as the line is readied for the next block of models, often coated in a color that is different from the previous block.

Offering a broad range of products makes frequent color changes a necessity.

“On our shed line we have a Nordson ColorMax® quick-changeover system that allows quick color changes,” Seegmiller said. “Before that we had a spray-to-waste booth. All of one powder color had to be emptied before another color could be added.“It actually took six manual sprayers to coat our product on that line,” he continued. “Since we were able to switch to that [quick-changeover system], now we have only two.”

Playing Out of Bounds. A powder coating line usually is just that—a line (as in, one line). Set up like a simple train track, a powder coating line usually takes a single path from origin to destination. However, some of the powder coating lines at Lifetime are set up differently, having spurs that leave the main track and later rejoin it for curing and packaging. Each spur leads to a different powder coating booth, meaning that each spur has a unique color.

“The hooks are fashioned so that one line grabs a part, and it goes through a separate line of a different color and then transfers the part back onto the main line and through the cure oven,” Miller said. “It’s pretty innovative. For visitors who look at the system, it’s kind of a jaw-dropper.”

Joining the PCI 4000 Club

The manufacturer sought the Powder Coating Institute’s PCI 4000 certification as both a goal and a knowledge resource, according to Miller. “The biggest reason we reached out for that was to make more resources available for us ... and to be part of the powder coating community.”

Seegmiller said that having the PCI auditor come out to the plant to provide some of his insights was especially helpful. The auditor individually audited each one of the lines, looking at the processes and how the company handles quality control.

“Some of the things he looked at were whether we had consistency in our process; mil consistency; how we store, use, and then track our powder. We have that all climate-controlled. He looked at how we do our PMs [preventive maintenance] on our equipment,” Seegmiller said.Now others seeking the PCI 4000 have reached out to Lifetime to ask questions, he added. “It just opened up doors for us in that aspect.”

Shooting a Three-pointer

It was just a few decades ago that most folding tables were flimsy, at best. A slight bump would topple glasses and bring a rousing card game to a rapid and wet halt. Basketball hoop stands were one-size-fits-all and supported little more than the basketball hoop, and coolers weren’t bear-proof. The company has a large number of such customer testimonials, many accompanied by photos, that attest to the robustness of its products.

These are the Lifetime innovations that customer see, but many more are behind the scenes.

Many OEMs don’t bother making tube or profiles. Tube mills and roll forming lines take up a lot of floor space, finding seasoned operators isn’t easy, and training an operator from scratch can be a long process. Such mills can be finicky, and an operator without substantial training and the savvy that comes from experience is at the mercy of the mill. Considering these hurdles, why make an intermediate good that is readily available?

Economics comes into play. Far more tube mills are located east of the Mississippi than west of it, and many in the west are dedicated to energy products. Trucking tube and profile over a long distance is a losing proposition; in many cases, a tube’s volume or a profile’s cross section is mainly air, and it’s hard to justify transporting air. Although investing in a few mills is too much for many companies to justify, Lifetime went this route and has been making the feedstocks for its products for many years.

In addition to making these feedstocks at lower cost than the company would pay for purchasing them and trucking them in, the company benefits in a second way: It generates some additional revenue by making tube to sell to other fabricators in the region.

Regardless of the motivation, the company’s decision to make its own tube and profile, and its execution in doing so, are further testimony to the ingenuity of the members of the engineering and manufacturing departments. It also hints at the company’s growth, which is a proxy for the value of its products. If the company weren’t delivering good products at fair prices, it wouldn’t have grown as much as it has, and it wouldn’t have the resources needed to integrate vertically.

Lifetime’s reliance on tube and profile made in-house also points to its control over product quality. Bringing in coil and working it from there gives the company all the control, and responsibility, that it could want over the integrity of its products, start to finish. After all, at the end of the day it’s not about finishing 100,000 parts. It’s about finishing 100,000 parts that will last a lifetime despite supporting the weight of a swordfish, successfully lifting an engine block, or standing up to a grizzly attack.

About the Authors

Eric Lundin

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8262

Eric Lundin worked on The Tube & Pipe Journal from 2000 to 2022.

Kate Bachman

Contributing editor

815-381-1302

Kate Bachman is a contributing editor for The FABRICATOR editor. Bachman has more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor in the manufacturing and other industries.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

HGG Profiling Equipment names area sales manager

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI